This story is summarized from Valentina Suntzeff’s unpublished autobiography, which can be found in the Valentina Suntzeff Papers in the Bernard Becker Medical Library Archives.

Early Life

Valentina Davidovna was born in Kazan, Russia on February 28, 1891. Her father was a physician, and he encouraged Valentina to pursue medicine at a young age. When she entered the St. Petersburg State I. P. Pavlov Medical University (also known as the Women’s Medical Institute) in 1911, there were no coeducational medical schools in Russia. However, as she noted in her autobiography, each of the four all-female medical schools in Russia were of equal caliber to the ten all-male schools, and female doctors were respected equally among their patients.

She married Alexander Suntzeff, a mechanical engineering student in St. Petersburg, and became pregnant during her second year of medical school. She took a year off to take care of their daughter, Ludmilla. During this time, her husband secured an engineering job with the Russian army in his hometown of Perm. They moved in with Alexander’s parents in Perm, then Valentina returned for her junior and senior year in St. Petersburg while her husband and daughter remained in Perm. In her autobiography, Valentina admits she could not have completed her education without the support of her husband and in-laws.

Despite Russia’s heavy involvement in WWI, Russian medical schools remained open in order to maintain the supply of doctors available to serve in the army. Valentina saw very little of her husband and daughter for two years while she completed her medical degree, which compounded her already stressful life of subsisting on wartime rations in St. Petersburg and keeping up with the rigorous medical school curriculum. Even when Valentina’s schedule allowed her to visit her family, she couldn’t always do so because the rail system was controlled by the army during the war and was therefore sometimes unavailable for civilian use. Moreover, the journey from Perm and St. Petersburg required a two-day train ride each way.

Revolution in Russia

During her last semester of medical school, Valentina witnessed the February Revolution that led to the end of the monarchy in Russia and the creation of a provisional government in St. Petersburg. Upon graduation in 1917, she returned to Perm to be reunited with her family. She immediately secured employment in the army as one of eight staff physicians at a large ammunition plant. Only a few months after starting her new position, the city was occupied by communist insurgents who had begun organizing across the country to form the Red Army in support of the ongoing Bolshevik Revolution. With the ammunition plant in the hands of the Red Army, Valentina and Alexander, who were both serving in the anti-communist White Army, escaped the violence with their daughter and other members of their family by boarding an evacuation train to eastern Russia.

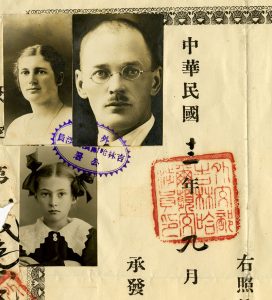

Unable to return to Perm, Valentina served as a medical officer in the White Army where she was ordered to a post in the town of Chita in southeastern Russia. For three years she treated soldiers who were injured fighting in the Russian Civil War. As the resistance to communism in Russia collapsed region by region, Valentina and her family were forced to evacuate once again, this time to Harbin, China. The family spent three years in Harbin waiting for the Russian Revolution to end. During this time, Valentina found work splitting her time between the Central Hospital in Harbin, a railroad hospital and private practice.

At the end of the revolution, the Soviet Union was formed on December 31, 1922. Valentina and Alexander, with their former ties to the White Army, had no hope of returning to their home without facing arrest. They decided to immigrate to the United States in 1923.

Coming to America

In October 1923, the Suntzeff family sailed from China to California by way of Japan and Seattle. They eventually settled in San Francisco with Alexander’s brother, who had immigrated to the U.S. the year before. Valentina was unable to find work as a physician in her new country. She attributed this problem equally to gender discrimination and her lack of fluency in English.

Despite Valentina’s appreciation for her new country’s intellectual freedom and relative tolerance of opposing political views (she remained ardently anti-communist throughout her lifetime), she was baffled by the lack of respect for female physicians and for women pursuing careers in medicine and science. This intolerance was something she had not experienced in Russia.

A Career on Hold

Instead of continuing her medical career, Valentina was forced to work at a sewing factory to make ends meet. Alexander was also unable to find employment in his chosen profession, despite holding an advanced degree and eight years of experience as a mechanical engineer in Russia. He took an apprenticeship to learn how to upholster furniture. During this time, the family lived on a mere $12 per week. After only a few months, Alexander was hired by an upholstery shop and his improved wages made life a little easier for the family.

The Suntzeffs settled into life as a seamstress and an upholsterer within San Francisco’s large ethnic Russian population. Yet for both Valentina and Alexander the desire to continue their former careers remained strong. Four years passed before Alexander was finally able to secure a job as a mechanical engineer at a match factory in St. Louis. The Suntzeffs moved to Ferguson, Missouri, located just outside of St. Louis, in 1930.

Unfortunately, Valentina found her job prospects in St. Louis were no better than they had been in San Francisco. She applied for internal medicine positions at many of the local hospitals and for numerous jobs in preventive medicine at the city health department. Valentina again attributed her rejected applications to her “broken English and being a woman.”

Finding Fulfillment in Cancer Research

Finally, in 1930, after being out of the medical field for nearly eight years, Valentina decided to enter a different field. She had primarily been responsible for treating soldiers and civilian patients in her previous life in Russia, but she applied to be an unpaid volunteer researcher in the pathology department of Washington University School of Medicine.

The head of the department, Leo Loeb, recognized her talent immediately. After only three months as a volunteer, Valentina was awarded a research fellowship to study the concentration of lactic acid in the blood of normal and cancer-bearing mice. Although she was no longer treating patients, she admitted, “it was the delight of my life to return to the medical field.” In 1934, Valentina was promoted to research assistant in pathology, where she researched the role of endocrine glands in the development of cancer.

A Stellar Career

In 1941, Valentina Suntzeff transferred to the Department of Anatomy when she became a research associate in cancer research. Although she was always sensitive about her accent when speaking English, she mastered writing in English. During her career at Washington University, Valentina authored or co-authored over 90 scientific publications. Most notably, her collaboration with biochemist Christopher Carruthers led to their discovery of a fundamental difference between the chemical composition of cancerous and normal tissues.

Valentina’s superior research skills and rate of publication earned her a promotion to research associate professor in 1958. Although university policy required her to officially retire at the age of 67 in 1960, Valentina continued her cancer research for another 15 years as research associate professor emeritus and lecturer in anatomy. She worked until the final year of her life and died in 1975.