The Glaser Gallery is located on the seventh floor of Bernard Becker Medical Library and houses rotating exhibitions of rare books, photographs, documents, and artifacts from the collections of the Archives and Rare Books Division. The gallery is free to visit and open to the public Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

A generous gift from Helen and Robert Glaser, who both had strong connections to the Washington University Medical Center, has allowed the Archives and Rare Books Division to exhibit items from its collections since 1990. Helen Glaser graduated with the Washington University School of Medicine class of 1947 and then completed her residency at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. Robert Glaser was an Intern and then Chief Resident at Barnes Hospital. He later became an Associate Professor of Medicine and Associate Dean at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

New exhibits are installed in the gallery three to four times each year. The titles of the current and past exhibitions in the Drs. Helen H. and Robert J. Glaser History of Medicine Gallery are provided here.

Printers’ Marks in the Glaser Gallery

One of the most distinctive features of books printed during the early modern period is printers’ marks. These symbols, which ranged from simple to elaborate, frequently appeared on the title pages of books. While the first title pages were quite minimalist and usually only included the work’s title, printers soon realized it was the perfect place for displaying trademarks. Their original function was to help protect a printer’s output from piracy, but as they became increasingly eye-catching, they also started to serve as a marketing tool. A distinctive printer’s mark displayed on a piece with fine craftsmanship branded that printer’s name with a reputation for quality.

The marks on the Glaser Gallery’s shades are all taken from the medical library’s collections. As is typical of Renaissance printers’ marks, they incorporate biblical and classical imagery. Some are famous in the history of print, and some were used by printers who were more obscure, but all reflect the beauty of their tradition.

Johann Froben

The Froben press was founded by Johann Froben (1460-1527). Born in the German city of Hammelburg in Franconia, he worked for Nuremberg-based printing magnate Anton Koberger before moving to Basel, where he quickly became involved in the city’s robust network of printers. He initially worked at Johann Amerbach’s press, and became a citizen of Basel in 1490. In 1491, he printed his first independent work, a Latin Bible, and continued to collaborate with prominent printers. He continued to collaborate with Amerbach and another prominent Basel printer, Johann Petri, and eventually assumed responsibility for seven presses. He employed many prominent humanist scholars in his print shops as correctors and compositors, the most famous of which was Erasmus of Rotterdam. In 1516, Froben published Erasmus’ extremely influential Greek translation of the New Testament, the Novum Instrumentum omne, which was one of the most influential publications of the humanist movement.

The mark of the Froben press was designed by Hans Holbein the Younger, a court painter for Henry VIII of England. It is a variation of the caduceus staff carried by the Greek god Hermes and depicts two hands coming out of the clouds to grasp a staff that is surmounted by a dove, while two crowned snakes surround the staff itself. In depictions of Hermes, the staff itself usually winged; the choice to replace the wings with a dove might be in reference to the Biblical verse Matthew 10:16, “So be as shrewd as snakes and harmless as doves.”

Johannes Oporinus

Johannes Oporinus (1507-1568) was another one of the great 16th century printers who worked in the city of Basel. He was born in Basel to the artist Hans Herbst and his wife Barbara Lupfart and educated in Strassburg. He taught at the cloister school of St. Urban in Lucerne before returning to his home town, where he became a teacher at the school of St. Leonard and worked as a corrector for the press of Johann Froben. He began his own career as a printer in the mid-1530s, working in a partnership with three other men. By 1542 his initial partnership had dissolved and he was working independently. The texts he printed were known for their high degree of accuracy, probably due to his humanist training. He also maintained a correspondence network that encompassed scholars, booksellers, and publishers, which helped boost his reputation as a reputable printer among scholarly circles. He is most famous for printing the first Latin edition of the Quran in 1542, and for the first and second editions of Andreas Vesalius’ beautiful anatomical atlas De humani corporis fabrica (1543 and 1555). At its peak, his operation had six presses run by roughly thirty people.

Oporinus’ mark refers to the story of Arion and the dolphin. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Arion was a musician of extraordinary talent who traveled to Sicily and Italy to make his fortune. During the return journey, the ship’s crew plotted to rob him and make him kill himself. Arion persuaded the crew to let him give one last musical performance, and upon its completion, he leaped overboard and was miraculously rescued by a dolphin and carried ashore. On Oporinus’ mark, Arion and the dolphin are surrounded by the words Invia Virtuti Nulla Est Via (No way is impassable to virtue), which were spoken to Aeneas by the Sibyl in the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Christoph Plantin

Christoph Plantin (c.1520-1589) was one of the most commercially successful printer-publishers of the 16th century. He was born near the French city of Tours but made his way to the Dutch city of Antwerp around 1548 where he worked as a bookbinder. In 1555, he established his own printing press, which he named the Officina Plantiniana. The press’ output included literary, liturgical, and scholarly texts, of which the most famous was the Plantin Polyglot, a multilingual edition of the Bible printed in Greek, Hebrew, Syriac, and Aramaic with accompanying Latin translations. The Plantin press was also known for publishing books with beautiful engraved illustrations and helped popularize engravings as opposed to woodcuts as the illustrative format of choice.

Plantin’s mark depicts a hand holding a compass and the motto Labore et Constantia (By Labor and Constancy). The image actually depicts the motto’s words: the center point of the compass represents constancy, while the circle drawn by the compass represents labor.

The Giunti Press

The Giunti was one of the most prominent Renaissance publishing families. Their involvement with the fledgling print industry began when Lucantonio Giunta, the son of a Florentine wool merchant, left Florence in 1477 to enter the stationery trade in Venice. He was so successful that in 1489 he decided to expand into the publishing business. In 1491, his older brother Filippo began publishing in Florence, and the siblings entered into a partnership that lasted until 1510. In 1519, Lucantonio’s nephew Giacomo began to work with him in the Venetian firm, and the following year Giacomo left to establish a branch of the family business in Lyon. The Giunti maintained more satellite branches in Rome and Spain, making it one of the most widespread, well-connected families in the early modern print industry.

The mark of the Giunti depicts a fleur-de-lis, which is the crest of the family’s native city of Florence. This mark was used by all branches of the publishing firm regardless of where a specific press was located.

Christoph Froschauer

Christoph Froschauer I ran the first printing operation in Zurich. He printed his first text in 1521, and quickly became one of the most prominent printers of the Reformation. He printed many of the works authored by the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli, and more than twenty editions of the Bible. Froschauer also printed the works of the naturalist and bibliographer Conrad Gesner. Gesner’s two most influential works were the Bibliotheca universalis, a “universal bibliography” that attempted to list all of the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew volumes published during the first century of printing; and the Historia animalium, considered a pivotal text in early zoology. The printing of the latter was carried out by two generations of Froschauers. Christoph Froschauer I printed the first set of volumes, but the project was completed by his nephew, Christoph Froschauer II, who assumed control of the firm upon his uncle’s death.

This version of Froschauer’s mark is a reference to the name. “Frosch” means “frog” in German, and the mark is a whimsical image of a child cavorting with a group of frogs.

Andreas Wechel

Andreas Wechel (1510-1581) was a German printer and bookseller. He was the son of the Parisian printer Christian Wechel and assumed control of the family printing firm in 1553. He and his family departed from Paris in 1572 because they were in danger due to their Calvinist beliefs. They narrowly escaped the murder of Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) that occurred in the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre. After they fled, they settled in the German city of Frankfurt, where Andreas reestablished his printing enterprise. After his death in 1581, the firm passed to his sons-in-law, Claude de Marne and Johann Aubry I.

Wechel’s mark incorporates several symbols. The most prominent are Pegasus and Hermes’ caduceus, taken from classical mythology. The cornucopia also refers to classical mythology, as it was associated with numerous classical deities including Demeter and Fortuna. The mark also includes a monogram of Wechel’s initials surmounted by the so-called “Sign of Four,” a mystical symbol derived from the first two Greek letters in the name Christos: Χ and Ρ.

Jehan Petit

Jehan Petit was one of the most prolific French publishers of the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Between 1493 and 1520 he managed to publish more than a thousand books, which was one-tenth of the entire output of Parisian presses during the time period. He was one of four official publishers for the University of Paris. Many of the most skilled Parisian printers worked for him, and his presses were an important conduit for the publication of humanist texts. His business interests were not limited to Paris. He operated bookshops in Clermont and Limoges and had presses working for him in Lyons.

Petit’s mark is heraldic in nature. The central shield includes his initials (during the 16th century the letter “J” was not commonly used) flanking a fleur-de-lis, the traditional emblem of the French royal family. The shield is supported by two lions.

Gilles Gourbin

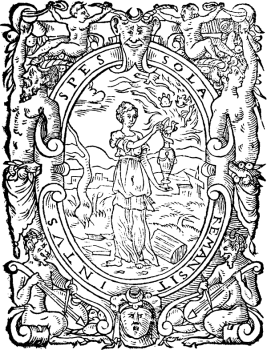

Gilles Gourbin was a French printer active from 1551 to 1590. His mark depicts one of the most well-known stories in classical mythology: Pandora and her box. In this story, Pandora was the first woman created by the gods. She was given a jar (enduringly mistranslated as “box” around this time) and told never to open it, for it held all kinds of evil, disease, and misery that would be inflicted upon the human race. One day, her curiosity got the better of her and she lifted the lid and released a torrent of misfortune into the world. Horrified by what she had done, Pandora slammed the lid of the jar shut, only to find it was too late. All that was left in the jar was hope.

The Gourbin mark shows Pandora opening her jar, and all of the evils escaping. The Latin motto Spes sola remansit intus means, “Only hope has remained behind.”

Sources of Information on Printers’ Marks:

Rudolf Schmidt: Deutsche Buchhändler. Deutsche Buchdrucker. Band 2. Berlin/Eberswalde 1903, S. 272-274.

Pfister, Arnold, “Froben, Hieronymus” in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 5 (1961), S. 637-638.

Bonjour, Edgar, “Oporinus, Johannes” in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 19 (1999), S. 555 f.

Johannes Oporin. Index Typographorum Editorumque Basiliensium.

“Plantin, Christopher.” The Oxford Companion to the Book. : Oxford University Press, 2010. Oxford Reference. 2010.

William A. Pettas. “An International Renaissance Publishing Family: The Giunti.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, Vol. 44, No. 4 (October 1974): 334-349.

Cole, Richard Glenn. “Froschauer, Christoph.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. : Oxford University Press, 1996. Oxford Reference. 2005.

Deutsche National Bibliotek. http://d-nb.info/gnd/119865130

Lucien Febvre. The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800. Translated by David Gerard. London: NLB, 1976.