About the Exhibit

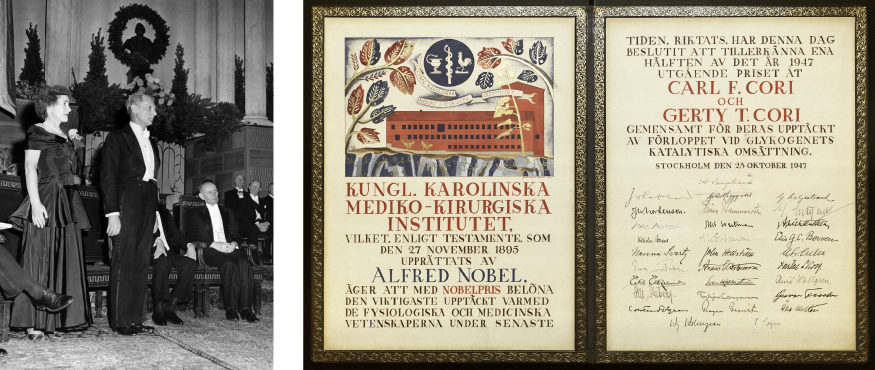

The two Nobel Prize medals awarded to Carl and Gerty Cori in 1947 for their groundbreaking medical research have been donated to Washington University in St. Louis by their son, Thomas Cori. Two replica medals made from the same cast were also donated, and the replicas are now on permanent display at The Center for the History of Medicine on the sixth floor of Bernard Becker Medical Library. The original medals are stored in the Archives and Rare Books Division on the seventh floor for safekeeping, but are available for viewing upon request. The exhibit also features other Nobel Prize-related items as well as instruments used in the Cori Lab.

The 1947 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

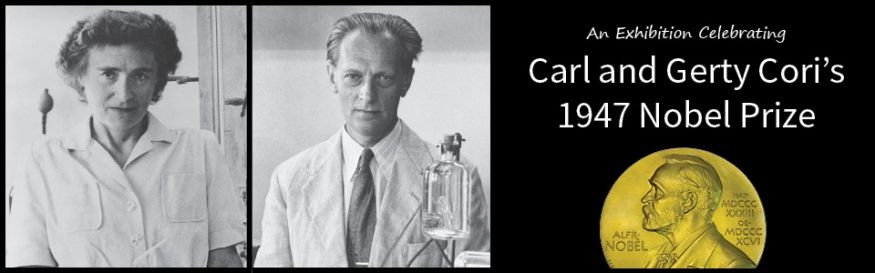

In 1947, when the Coris were awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, Gerty Cori was the first American woman to win a Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, and the couple was the third husband-wife team to win Nobel Prizes together.

Carl and Gerty Cori received their Nobel Prize “for their discovery of the catalytic conversion of glycogen.” They shared the prize that year with Bernardo Houssay of Argentina. Carl Cori described his research collaboration with his wife in his speech at the Nobel banquet in Stockholm in December 1947: “Our efforts have been largely complementary, and one without the other would not have gone so far as in combination.”

Carl and Gerty Cori

In 1896, Carl Ferdinand Cori and Gerty Theresa Radnitz were born in Prague. The two met in 1914 while in medical school at the German University of Prague, however, their education was interrupted by World War I. Carl was drafted into the Austrian army and he didn’t see Gerty again until after the war when they returned to school. The Coris enjoyed a milestone year in 1920 in which they published the results of their first research collaboration, received their medical degrees, got married and moved to Vienna all in the same year.

As the Coris became increasingly unsettled with the socio-political environment in Eastern Europe in the early 1920s, they began exploring career opportunities overseas. In 1922, Carl accepted the position of biochemist at the State Institute for the Study of Malignant Disease in Buffalo, New York (now known as Roswell Park Cancer Institute). Gerty was able to secure an assistant pathologist position at the institute six months later, kicking off what would become an immensely successful 35 years of research together.

After spending nine years in Buffalo and publishing more than 50 papers together, Philip Schaffer, dean of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, offered Carl the position of chair of the Department of Pharmacology in 1931. Carl accepted the appointment and Gerty joined him in his lab at Washington University later the same year.

Carl proved to be a very capable department head at the School of Medicine. He was particularly successful in recognizing talent and recruiting very gifted students, fellows and faculty to his lab. Gerty was a highly valued and meticulous researcher and earned several promotions including becoming a full professor in biological chemistry in 1947, the same year the Coris were awarded the Nobel Prize.

Unfortunately, 1947 was the same year in which the Coris learned that Gerty had developed myelosclerosis. She suffered through this disease for 10 years, never stopping her research until the last few months of her life. Gerty died in 1957 at the age of 61. Carl stayed at Washington University until he retired in 1966. He later accepted a visiting professor position at Harvard. Like Gerty, Carl continued his research until the end of his life and was still publishing papers at the age of 87. Carl died in 1984.

The Coris’ Legacy

The Coris’ most notable contribution to science was their series of discoveries that elucidated the pathway of glycogen breakdown in animal cells and the enzymic basis of its regulation. Those discoveries formed a linear sequence that fell into four parts: the Cori cycle, or the cycle of carbohydrates (1922-31); glucose-1-phosphate, which became known as Cori ester (1931-37); phosphorylase and the cellular pathway of glycogenolysis (1937-44); and the regulation of phosphorylase (1945-52). In a biographical memoir published in 1986, Sir Philip Randle noted that Carl and Gerty Cori’s research “was characterized above all else by intellectual rigour applied with equal force to experimental methods and techniques (physiological and chemical); to a profound knowledge and critical appreciation of the literature; to a generally dispassionate, though sometimes defensive, analysis of discrepancies; to a high degree of replication especially in animal experiments; and to a meticulous attention to detail especially in formulating hypotheses.”

The couple’s lasting legacy included the training of successive generations of scientists – no fewer than six other future Nobel laureates worked with Carl and Gerty Cori at their laboratory at Washington University: Christian de Duve, Arthur Kornberg, Edwin G. Krebs, Luis F. Leloir, Severo Ochoa and Earl W. Sutherland.

In 2004, the Cori Lab at Washington University was designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark. A commemorative plaque marks the location at the entrance to the South Building at 4577 McKinley Ave., St. Louis, Mo.