In the continuing process of digitizing documents and materials in the Bernard Becker Medical Library Archives, new scans of St. Louis Children’s Hospital publications are now available online in the archives database. These include about a decade’s worth of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Bulletin, an internal publication of the hospital.

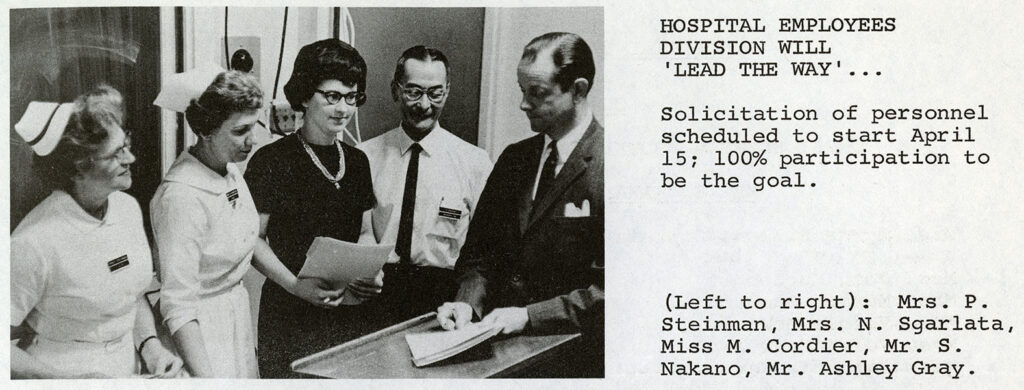

In the December 1967 issue of the Bulletin, there is a short notice mentioning the retirement of the hospital’s comptroller, Stewart Nakano. As comptroller Nakano was a trusted and valued member of the senior hospital staff. In 1963, he served as a co-chair on a hospital fundraising campaign. At his going-away party, the hospital’s dietetic staff prepared a special meal. In an accompanying photograph to the article, Mr. Nakano and his wife, Alice Ohashi Nakano, are seen together at the staff party in his honor.

Both Mrs. and Mr. Nakano were originally from Stockton, California in the agricultural heart of the Central Valley. Alice was born in California in 1913. Stewart was born in Hawaii in 1904. Both of them, including Alice’s family, came to the Midwest in 1942 when they were forcibly removed from their homes and relocated to a concentration camp in Arkansas by the order of the President of the United States.

On February 19, 1942, two months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. This order, citing military necessity in time of war, was used by US military commanders on the West Coast to incarcerate over one hundred thousand Japanese-Americans during World War II. While the order was not specific to ethnicity, it was nearly exclusively applied to Japanese-Americans living in the Pacific States.

While some in the Roosevelt administration opposed the order, including US Attorney General Francis Biddle and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, the mass forced removal of Japanese-Americans began in early 1942 under the US Army. In fact, the Justice Department and FBI working with local law enforcement had already arrest over a thousand Issei, or Japan-born people, shortly after Pearl Harbor. Issei is the term within the Japanese-American community for “first generation” immigrants from Japan.

Not until a month later was a civilian government agency created to oversee what was then called the “internment” process. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was created by Executive Order 9102 on March 18, 1942. The miliary operation had already been removing Japanese-American from their homes and forced them into temporary “assembly centers” quickly constructed on fairgrounds or racetracks until larger, more “permanent” camps could be constructed in the nation’s interior. All Japanese-Americans, both the first-generation Issei as well as those born in the United States with full citizenship, the second-generation Nisei and third-generation Sansei, eventually were to be removed from the West Coast States. Regardless of age, all men, women, and children, entire families had to leave behind their homes, work, school, pets, and most of their belongings. They could take only what they could carry.

In the spring of 1942, Stewart Nakano and the Ohashi family, father Kanzo Ohashi, his son Ted Ohashi, and his two daughters, including Alice Ohashi, were forced to leave everything and were incarcerated in the Stockton Assembly Center, which was hastily built on the site of the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds southeast of downtown Stockton.

The first director of the WRA was Milton S. Eisenhower, the younger brother of General Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower. The younger Eisenhower was a proponent of Roosevelt’s New Deal and had several positions in the Department of Agriculture. He also disapproved of the idea of mass internment. He tried initially, but failed, to limit the internment only to adult men, allowing children and women and children to remain in their homes. But he was able to set up a “work corps” program allowing Nisei to work outside the camps, to continue to enlist in the US Army, and also enabling those who had been in college on the West Coast to attend colleges elsewhere which would accept them. This led to the creation of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council.

Eisenhower resigned as director of the WRA after only ninety days. In a letter shortly before his resignation, he wrote, “when the war is over and we consider calmly this unprecedented migration of 120,000 people, we as Americans are going to regret the unavoidable injustices that we may have done.”1 His successor, Dillon Myer, tried to create a framework by which the WRA would work with the incarcerated communities primarily liaising with members of the of Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), which was founded in 1929.

Stewart Nakano was an active member of the JACL before the war. He was elected the treasurer of the Sacramento Chapter of the JACL in 1934.2 And he was president of the Stockton Chapter in 1937. Nakano was also the past president of the Stockton American Loyalty League. Immediately after Pearl Harbor, he was asked to speak to the Pacific Japanese Students Club at which a plan of action for young Japanese-Americans would be agreed on “so that they may do their duty as good citizens” according to the meeting announcement.3 However, Nakano’s American citizenship did not protect him from his incarceration and removal.

At the intermediate “assembly centers” the incarcerated were left to recreate a community as best as they could. A local newspaper, El Joaquin, was published showing the efforts and activities of the camp inmates. Nakano was made the superintendent of the schools.4 And as a Phi Beta Kappa graduate in Economics from Stanford University he was also on a committee on cooperatives and the economic life of the camp.5

But the time in the Stockton assembly center was short, and in the Fall of 1942, all of the detainees were placed on trains and sent to Camp Rohwer in Arkansas, which was carved out of a swampy forest in the river delta only ten miles from the Mississippi River. The train journey, which was a cramped ordeal under armed guard, took over three days. They were told to close their window blinds as they passed through every station so the local inhabitants wouldn’t see the occupants.

Stewart was an early arrival at the camp on October 17, 1942.6 He was likely elected a block captain to help prepare the camp for the rest of the internees. The camp was still unfinished in the fall of 1942. Eventually, over eight thousand people would be incarcerated there. Alice Ohashi and her family arrived in late November.

Along with Alice were her brother Ted Ohashi and her father, Kanzo Ohashi. Kanzo was a newspaperman, a branch manager of the Nichi Bei Times of Stockton and longtime correspondent for the Shinsekai newspaper before the war.7 And in 1937 he published Hokubei Kashu Sutakuton dohoshi [History of the Japanese in Stockton, California] which is a chronology of events between 1910 to 1936 of the Japanese American community in the Stockton area covering anti-Japanese racism as well as the community’s participation in state-wide affairs.8 At Rohwer, Kanzo helped out with that camp’s newsletter, the Rohwer Outpost.9 Stewart Nakano also again joined the schools but this time as an instructor in commerce.10

The directors of the WRA, Eisenhower and his successor Myer, were successful in allowing the relocated to find roles in the local communities. By 1943 some people were being released from Camp Rohwer for war-time employment as farmworkers or as factory and office workers as far as St. Louis and Chicago.

One relocated individual, Tomi Domato, corresponded with family, keeping tabs on the happenings at the camp and elsewhere. In a letter on November 30, 1942, they write that Alice Ohashi and Stewart Nakona had been married in the camp.11 In a later letter, Tomi, by then released to work in St. Louis, mentions that others from Rohwer now in St. Louis included Stewart, Alice, and her brother Ted.12 13

Young people attending colleges on the West Coast also had their studies cancelled by the internment order. The WRA set up a system to allow these students to continue their studies at other institutions further east, if they would have them. Washington University was one of the institutions that welcomed them. Two students who continued at WashU were Gyo Obata and George Sato.

Obata graduated in 1945 and became a celebrated architect. Founder of Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum (HOK) his designs ranged from the iconic James S. McDonnell Planetarium at the Saint Louis Science Center, to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Japanese American National Museum Pavilion in Los Angeles.14

George Sato entered an accelerated medical studies program at WashU and graduated from the School of Medicine in 1947. After training in pediatrics, he practiced for many years in St. Louis. He was on staff at many area hospitals including Barnes-Jewish Hospital and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, where he served as president of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital’s Medical Staff Society. In 1981 he was awarded the WashU Alumni Association Award for dedicated service.

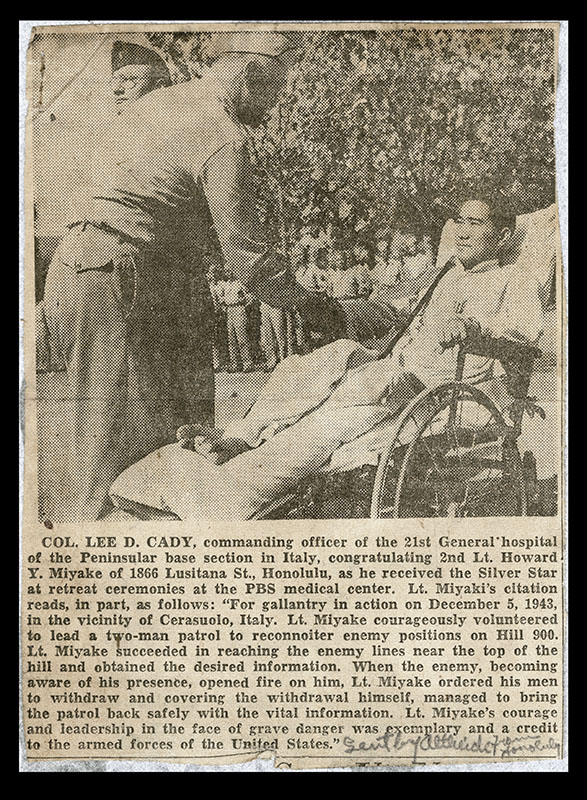

WRA director Myer, along with a campaign by members of the JACL, was also successful in making Nisei eligible again for military service. The result was the formation of the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The regiment would see combat in Italy and in France. Within the regiment was the 100th Infantry Battalion recognized as the most decorated unit in U.S. military history. Wounded members of the 100th would be treated at the 21st General Hospital, the army reserve hospital staffed by members of the WashU and medical center community.

The 21st eventually dedicated one of their rehabilitation rooms in honor of the 100th, named the “Hawaiian Room” as many of the 100th had been members of the Hawaiian national guard before internment and later release to join the 422nd.

After the war and when the interment order was no longer in affect the Nakano’s stayed in St. Louis. In September 1945 Stewart and Ted Ohashi were elected to serve on the Nisei Council of St. Louis.15 Eventually Ted and his father Kanzo Ohashi returned to California. After his wife died in 1960, Kanzo moved to St. Louis to live with the Nakanos. He died in 1963.16

Over 60% of those interned, nearly 70,000, were American citizens like Alice and Stewart Nakano. Many of the rest were long-time US residents who had lived in this country between twenty and forty years like Alice’s father. But it was a long time before the nation would address the injustice they faced. Not until 1952, when Congress passed the McCarran Walter Act, would Japanese immigrants again have the right to become naturalized US citizens. In 1976, President Gerald R. Ford symbolically rescinded Executive Order 9066. But it was not until the 1981 Congressional Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which held hearings across the country, that this history was addressed. The committee determined that internment was a “grave injustice” and that Executive Order 9066 resulted from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” On August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act, apologizing to the Japanese American internees and offering $20,000 to survivors of the camps.17

In his remarks on the signing, President Reagan clearly stated:

“For here we admit a wrong; here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.” He further said, in reference to his comments about the 442nd Regiment:

“Blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color. America stands unique in the world: the only country not founded on race but on a way, an ideal. Not in spite of but because of our polyglot background, we have had all the strength in the world. That is the American way.”

In signing the apology, he closed with saying, “I think this is a fine day.”18

In 1943, Stewart Nakano was asked by a church group to share his thoughts on the role of Christianity in achieving world peace and preventing injustice to Japanese Americans. In a speech entitled “My Aspirations for 1943.” His talk began with and centered around the ideal:

“’Love they neighbor as thyself.’ I am sure that all of us can think of many reasons for this aspiration, but may I briefly point out two. It is natural that we should first consider ourselves. The big question in our minds is what is to become of us who are citizens of this country but who have been uprooted from our homes and placed in these relocation centers. It puzzles us that the people of this country allowed this mass evacuation of citizens; but we must know the political setup of this country to understand. …

“But let us raise our sights from our community and look at this world. Isn’t it in a terrible turmoil? … It is beyond our conception how great is the suffering, borne so quietly and so bravely. And look at the hatred in this world. It is a sad state of affairs. … We cannot sit by and not take a part in the formation of policies for world peace. We must work for a lasting peace. We will be guilty of the greatest sin of omission if we do not work toward a lasting peace.“19

Only a fragment of the speech survives but it is clear that he placed his hope that humanity will learn to treat each other as each would wish to be treated themselves.

Stewart Nakano died on February 14, 1994. Alice Ohashi Nakano died July 2, 2001.

Much of the information about their lives and was made accessible by Densho, a nonprofit organization which takes and preserves oral histories from Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II and making these available online along with other documentation and letters. https://densho.org/ .

And by the Rising Above in Arkansas: Japanese American incarceration at Rohwer and Jerome during WWII website, a project made possible by a grant from the Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) grant program, administered through the National Park Service. https://risingabove.cast.uark.edu/home .

- Weigel, Larry. “Milton Eisenhower breaks color barrier at KSU,” The Mercury (Manhattan, Kansas) Sep 11, 2013. Updated Mar 31, 2017. Accessed December 2025. https://themercury.com/k_state_sports/milton-eisenhower-breaks-color-barrier-at-ksu/article_789f970a-5380-5583-8c1b-77a5a335c189.html ↩︎

- Complimentary Publication for the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Sacramento J.A.C.L. Chapter “Old Timers” (Years 1931-1942). Printed for the Golden Anniversary Celebration at the Sacramento Community Center, Saturday, November 14, 1981. Accessed December 2025. https://downloads.densho.org/ddr-csujad-55/ddr-csujad-55-2605-mezzanine-fff004492d.pdf ↩︎

- “Campus Japanese Call Meeting: Duty to America is Discussion Theme.” The Record (Stockton, CA) Saturday, December 13, 1941. Page 5. Accessed December 2025. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-record/109937631/

Accessed December 2025. https://oac4.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2q2nb283/entire_text/ ↩︎ - Stockton (detention facility). Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed December, 2025. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Stockton_(detention_facility)/

“Young students display much talent and originality in their work,” El Joaquin, vol. 3, no. 1 (August 22, 1942). Accessed December 2025. https://digitallibrary.californiahistoricalsociety.org/object/23178 ↩︎ - “Squeals from the hog barn: Hansen speaks on cooperatives.” El Joaquin, vol. 1, no. 8 (June 24, 1942). Accessed December 2025. https://digitallibrary.californiahistoricalsociety.org/object/23066 ↩︎

- U.S., Final Accountability Rosters of Evacuees at Relocation Centers, 1942-1946. Accessed December, 2025. Ancestry.com ↩︎

- “Obituary: Ex-newsman Ohashi dies in St. Louis,” Hokubei Mainichi (San Francisco, CA), January 30, 1963. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection. Hoover Institution. Stanford University. Accessed December, 2025. https://hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=hbmn19630130-01.1.5&e=——-en-10–1–img——— ↩︎

- History of the Japanese in Stockton, California. Downtown Brown Books. Accessed December, 2025. https://www.downtownbrown.com/pages/books/308077/kanzo-ohashi/history-of-the-japanese-in-stockton-california-hokubei-kashu-sutakuton-dohoshi?soldItem=true&srsltid=AfmBOoppt-zsjxliqMUzgoKrYFuTk1kvkFlpQlE0LUvT2xPu2ixRnKNN ↩︎

- The First Rohwer Reunion. Published by the First Rohwer Reunion Committee, Gardena, California, 1990. Densho Digital Repository. Accessed December, 2025. https://downloads.densho.org/ddr-csujad-1/ddr-csujad-1-50-mezzanine-42e5c1e944.pdf ↩︎

- “Nisei instructors appointed by board,” Rohwer Outpost, November 7, 1942. Densho Digital Repository. Accessed December, 2025. https://downloads.densho.org/ddr-densho-143/ddr-densho-143-5-mezzanine-c64ba955c2.pdf ↩︎

- Letter, Tomi Domoto to Yuri Domoto. November 30, 1942. Densho Digital Repository. Accessed December, 2025. https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-356-300/ ↩︎

- Letter, Tomi Domoto to Yuri Domoto. January 16, 1944. Densho Digital Repository. Accessed December, 2025. https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-356-378/ ↩︎

- “… Mr. and Mrs. Stewart Nakano, whose fine Christian influence was planted for a time in a relocation center and is now manifest in the city of St. Louis to which they have moved.” Comments by Joseph Boone Hunter, circa 1944-1945. Joseph Boone Hunter comments, circa 1944-1945. Rising Above in Arkansas: Japanese American incarceration at Rohwer and Jerome during WWII. Accessed December, 2025. https://risingabove.cast.uark.edu/archive/item/1863 ↩︎

- Remembering Gyo Obata, 2022-03-11. Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. Washington University. Accessed December, 2025. https://samfoxschool.washu.edu/the-school/news/463-remembering-gyo-obata ↩︎

- Rohwer Relocator, newsletter, Rohwer Relocation Center, McGehee, Arkansas. Vol. 1, No. 20. September 21, 1945. Densho Digital Repository. Accessed December, 2025. https://downloads.densho.org/ddr-densho-143/ddr-densho-143-316-mezzanine-3ab0fa5a4a.pdf ↩︎

- “Obituary: Ex-newsman Ohashi dies in St. Louis,” Hokubei Mainichi (San Francisco, CA), January 30, 1963. Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection. Hoover Institution. Stanford University. Accessed December, 2025. https://hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=hbmn19630130-01.1.5&e=——-en-10–1–img——— ↩︎

- JARDA: Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives. University of California. Accessed December, 2025. https:/web.archive.org/web/20140426214946/http:/www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/jarda/historical-context.html ↩︎

- Ronald Reagan, remarks on the signing of the restitution of internment. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum. Accessed December, 2025. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/remarks-signing-bill-providing-restitution-wartime-internment-japanese-american ↩︎

- Stewart Nakano “My Aspirations for 1943.” Rising Above in Arkansas: Japanese American incarceration at Rohwer and Jerome during WWII. Accessed December, 2025. https://risingabove.cast.uark.edu/archive/item/2105 ↩︎