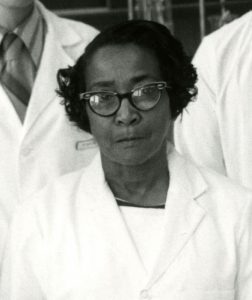

One of the great pioneers in research at Washington University School of Medicine was Lenabell McClelland Bell. Suffering from sickle cell anemia, she first came to Barnes Hospital in 1937 while pregnant with her first child. Sickle cell can create severe complications during pregnancy, however, Bell recovered and gave birth to a healthy girl. Periodic episodes of debilitating pain related to the disease – called “crisis events” – would bring her back to the hospital where she would become familiar with Carl V. Moore, MD, professor of medicine and head of the hematology unit.

Moore and his wife sometimes cared for Bell’s infant daughter while she was hospitalized. Bell became an active participant in Moore’s clinical teaching. Moore presented her case to students and trainees and she spoke with them about her experience of the disease. In the mid-1950s, a post-graduate trainee named Hugh Chaplin joined Moore’s hematology group. Chaplin, a graduate of Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, also became acquainted with Bell and she became a member of his laboratory group, working part-time as her health allowed.

In 1956 Chaplin and Bell began a long-term experiment testing the effectiveness of a new method of transfusion therapy. In sickle cell disease, the red blood cells, which carry oxygen throughout the body, are misshapen and inefficient in oxygen transport. The disease leads to irreparable damage to organ systems throughout the body and creates frequent “crisis events.”

In 1956 Chaplin and Bell began a long-term experiment testing the effectiveness of a new method of transfusion therapy. In sickle cell disease, the red blood cells, which carry oxygen throughout the body, are misshapen and inefficient in oxygen transport. The disease leads to irreparable damage to organ systems throughout the body and creates frequent “crisis events.”

At that time, transfusions of blood with normal red blood cells were the prevalent course of treatment for these crises. Unfortunately, repetitive transfusions were known to cause organ toxicity due to the increase of iron from the additional, normal red blood cells. Chaplin devised a method which he hoped would allow Bell and others with the disease to tolerate more transfusions without the toxic side-effects. The new method, called Partial Exchange Transfusion, would basically remove an equal amount of red blood cells from the patient while transfusing in the new cells.

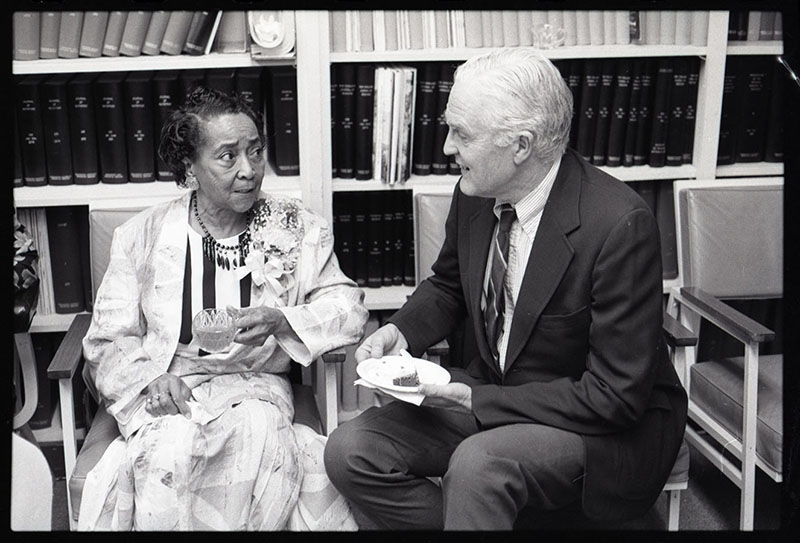

But the long-term consequences of partial exchange would need to be tested. Bell volunteered. Chaplin considered Bell’s role not simply as a patient but as a colleague in a joint research endeavor. Before beginning, they spent several weeks discussing all the risks and benefits, the long-range commitments by all parties, and the uncertainty of success. Bell and Chaplin worked together on the experimental trial, which lasted for over a decade.

Partial exchange transfusion remains an important method for making blood transfusions a safe treatment for sickle cell disease. Though the national median life expectancy for sufferers of sickle cell disease is 42–47 years, Bell lived to be 83, dying in 2000. Chaplin died in 2016.

Bell later told Chaplin her reasoning for undergoing the study. “I wasn’t frightened. I was pretty desperate. I had been sick so long. I was getting worse. I was hooked on Demerol. I was in pain most of the time; and there didn’t seem to be anything that anyone could do to help me. I knew you were trying to help me. It was my best chance. … I felt I had gotten to know you as well as I knew most of the other doctors in the Hematology Clinic. You know, I didn’t see any of them regularly. There were a lot of young doctors in the clinic. I’d see one of them one day, another on another day-whoever was assigned to the clinic that day. And I’d see different doctors when I was admitted to the hospital. You know, that’s how it is if you don’t have any money. You have to be rich to see your own doctor whenever you get sick. Once you were assigned to my case, I saw you every time I came to the clinic or the hospital. I felt I knew you very well, and I trusted you.”