Chances are you’re familiar with the phrase “A picture is worth a thousand words.” While this maxim originated with an American advertising firm in the 1920s, it is certainly applicable to images produced in early modern Europe. Many of the illustrative elements in books were meant to convey meanings on multiple levels. Elaborate title pages and frontispieces could introduce a work’s subject without the need for text, and historiated initials at the start of chapters contained clever allusions to the work’s content. Erudite readers enjoyed these sorts of visual games, and decorative elements were a standard part of early modern publications.

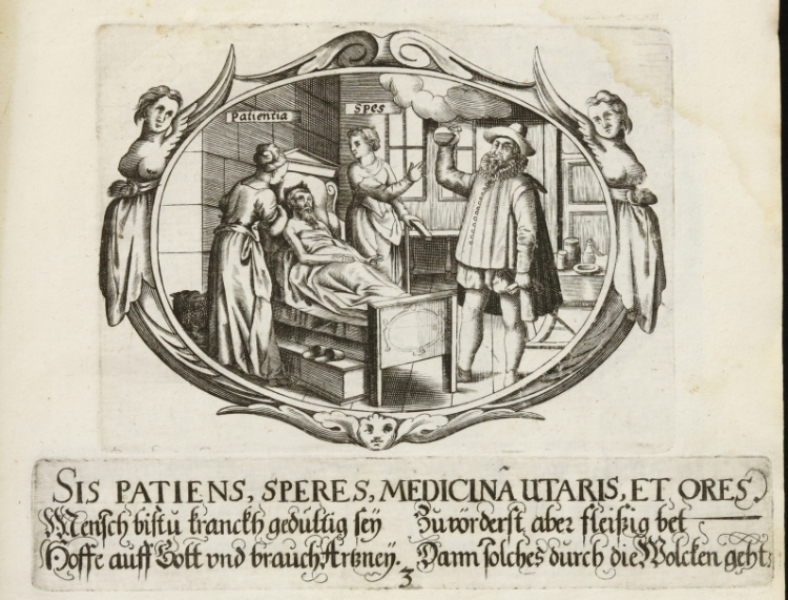

Medical texts also made use of clever visuals. We’ve talked about examples of this in previous blog posts, but here we’re focusing on one specific text: Johann Pfann’s Biblische Emblemata, a collection of engraved emblems printed in 1626. Emblems reached their zenith of popularity in the 1600s and are a quintessentially Renaissance invention, as they combine elements of humanist philosophy, religious thought, and classical imagery into a single unit that appealed to educated audiences. Emblem imagery often used Greco-Roman art and mythology as a basis for inspiration, but Pfann’s work is notable for basing its images on paintings that were originally created for the Heilig-Geist-Spital (Hospital of the Holy Spirit) in Nuremberg. This hospital was founded in 1339 by Konrad Gross when the city outgrew the 12th century Elisabethspital. Heilig-Geist was initially established north of the Pegnitz River with a planned capacity of 200 beds, but in 1487 the city agreed to enlarge it. An expansion over the northern arm of the Pegnitz was completed in 1518, and the structure has remained essentially unchanged since 1527—although the one we can see today is largely a 20th century reconstruction, as the original was heavily damaged during WWII.

Pfann’s images provide a glimpse into the world and culture of Heilig-Geist, which was the largest establishment dedicated to treating the old, infirm, and poor within the principality of Nuremberg. We see images of medical procedures including amputation, urinalysis, and paracentesis, alongside depictions of the elderly surrounded by their families, parents mourning a child, and the dead being buried. Beneath each image is a brief maxim in Latin, followed by a few lines in German that explain the image’s central lesson. These are largely aphorisms on how to live a morally upright life, reminders of the importance of faith, and the meaning behind earthly suffering.

Becker Library’s copy of Pfann’s emblems is currently on display as part of the exhibit Reading Text and Image, which examines the use of visual allegory and symbolism in early modern Europe. In addition to items from Becker’s rare book holdings, the exhibit also includes several outstanding works loaned to us by the Special Collections Department at Olin Library.