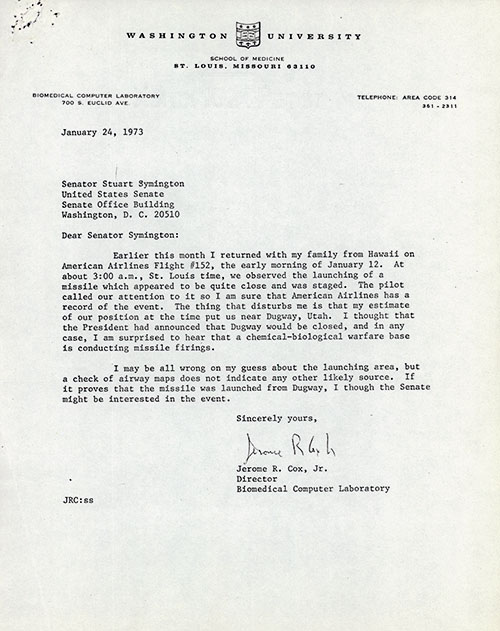

The year was 1973, and Jerome “Jerry” Cox and his family were en route from Hawaii to St. Louis on American Airlines Flight 152. In the early morning hours of January 12—Cox guessed around 3:00am, St. Louis time—the pilot called their attention to a staged missile launch visible from the plane. Based on their flight path, Cox estimated that the launch they observed likely originated in Utah. More specifically, and more troublesome to Cox, he thought the missile may have been launched from Dugway Proving Ground, a known site of chemical and biological weapons testing.

We know these details because Dr. Cox, then director of the Biomedical Computer Laboratory (BCL) at Washington University School of Medicine, kept a copy of the letter he sent to Senator Stuart Symington (MO) about the incident. “The thing that disturbs me,” he wrote, “is that my estimate of our position at the time put us near Dugway, Utah. I thought that the President had announced that Dugway would be closed, and in any case, I am surprised to hear that a chemical-biological warfare base is conducting missile firings.” He acknowledged he could be mistaken, but if the missile did originate from Dugway, he “though[t] the Senate might be interested in the event.”1

Thus began Dr. Cox’s quest to determine if, in fact, he witnessed a missile launch from Dugway Proving Ground. His efforts are chronicled in a sequence of letters, grouped together with a paperclip and located in a folder of correspondence filed under the letter “A” from his tenure as BCL director. Spanning January to September 1973, they contain communications between Cox and Senator Symington, American Airlines staff, and U.S. military officials. After formal inquiries, delays and digressions, and the occasional tense exchange, Cox’s pursuit of what really happened that winter morning reached a satisfactory—though, to him, still somewhat suspect—conclusion.

What can we learn—or not learn—from historical documents about the missile launch? About the time period? About Jerry Cox himself? Researchers look to primary sources to help explain the past. When interpreting content, we ask who created it, and when, where, and why they did so. We place materials in context: what was happening at the time, and how might it have influenced their creation? When possible, we seek out multiple perspectives. And, what we find informs the questions we ask, as well as how we attempt to answer them.

“We hope [this] answers your questions”: Dugway Proving Ground and CBW Policy

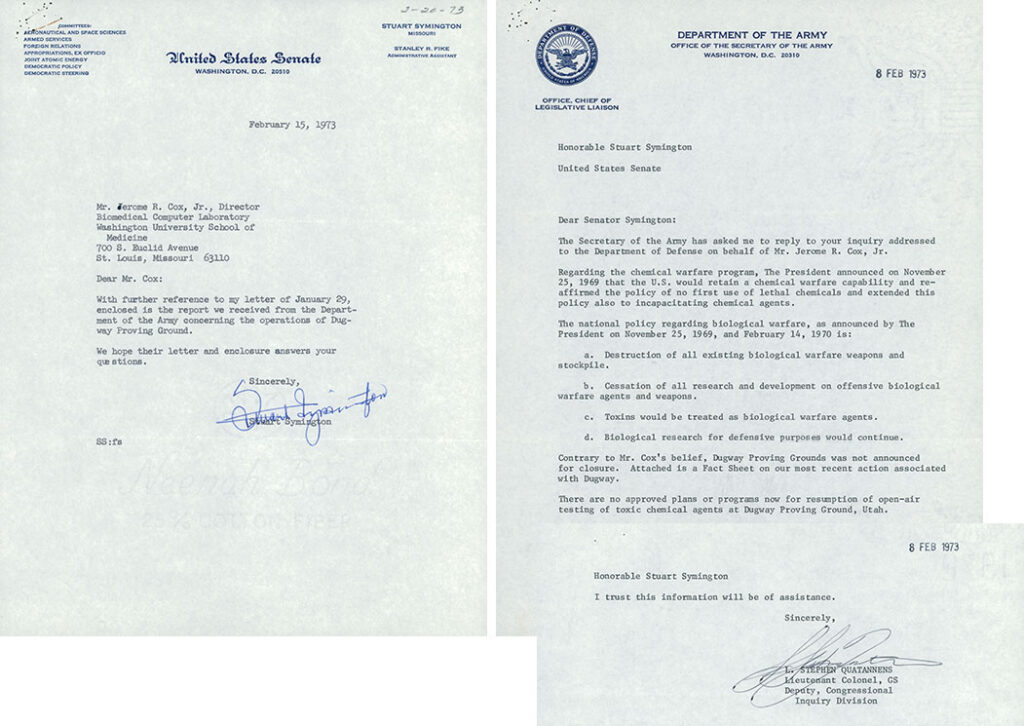

In response to Dr. Cox’s concerns about the launch, Senator Symington addressed an inquiry to the Department of Defense. He shared the Department of the Army’s reply with Cox in February, writing, “We hope their letter and enclosure answers your questions” (spoiler: they did not). The reply did clarify that while open-air testing of toxic chemical agents had ceased for the time being, Dugway Proving Ground remained open. It also outlined current U.S. policies on chemical and biological warfare (CBW)—policies that existed in part due to an incident connected with the very military facility that aroused Cox’s suspicions.

Letters from Senator Symington to Jerome Cox, February 15, 1973, and from Lt. Col. Quatannens to Senator Symington, February 8, 1973.

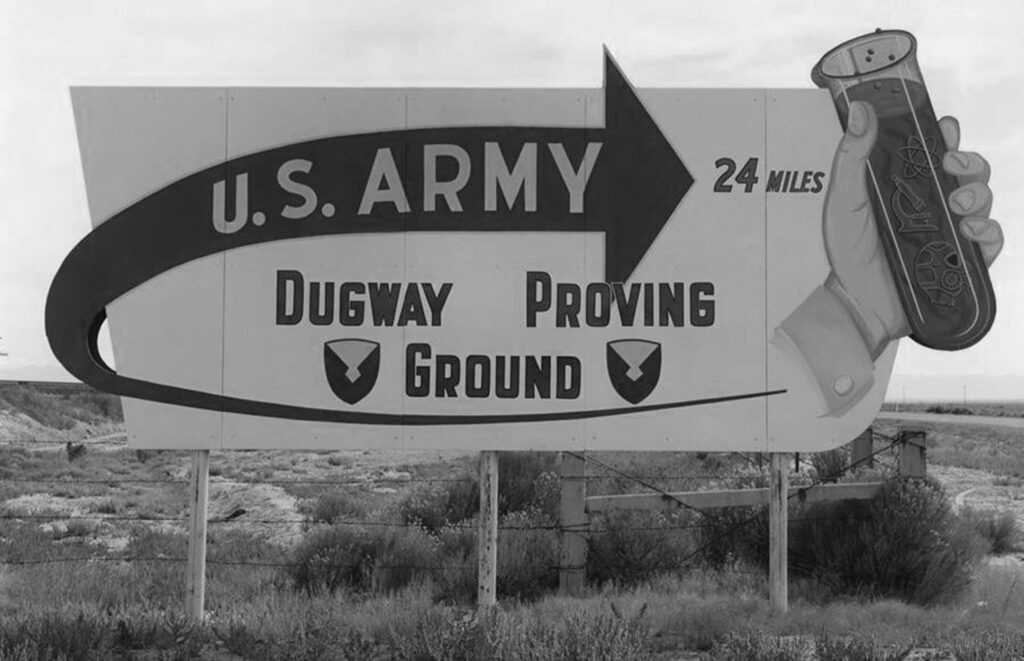

Located about 85 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah, Dugway Proving Ground was established in 1942 as a site for chemical and biological weapons testing. After a period of deactivation post-World War II, the facility was reactivated with the onset of the Korean War in 1950. Dugway became a permanent installation in 1954, and CBW testing continued apace until the late 1960s, when a chemical weapons test went badly wrong.

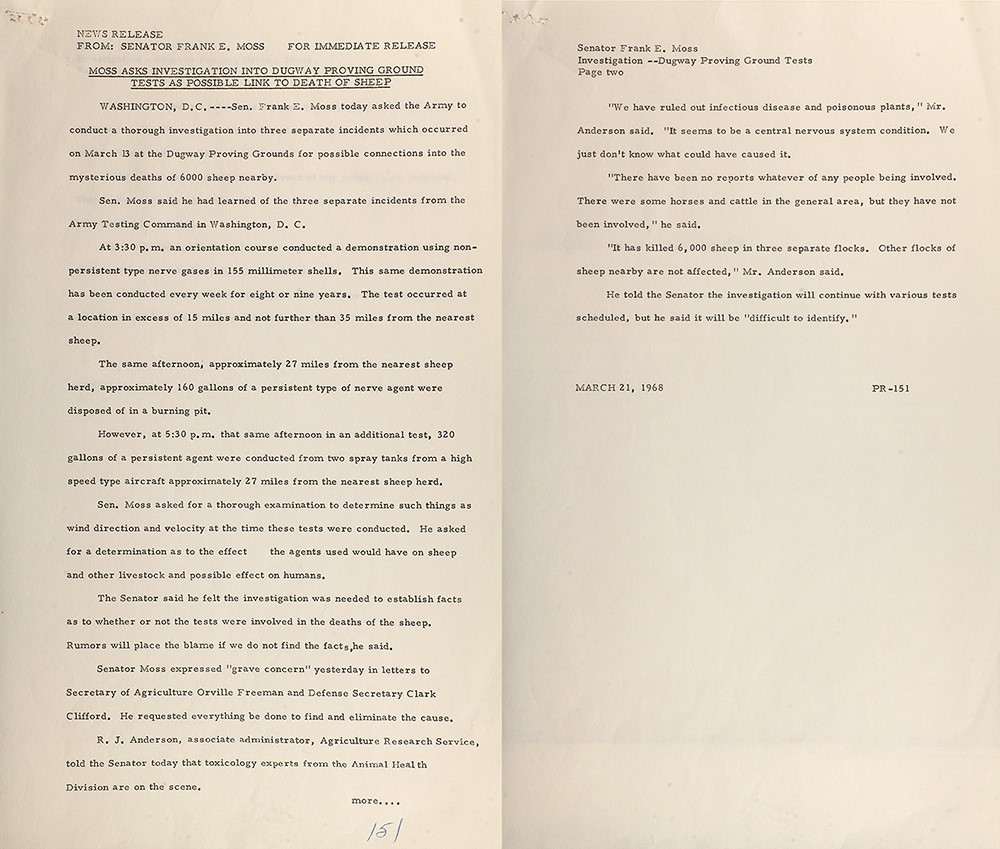

What came to be known as the Dugway sheep incident occurred in March 1968. On the morning of March 14, residents downwind of the facility awoke to a gruesome scene: where they normally saw livestock grazing the land, they instead saw thousands of dead and dying sheep. Publicly, the Army denied any involvement and claimed Dugway had not tested any weapons in recent days. Privately, Utah Senator Frank Moss had been briefed otherwise, and, to the surprise of Army officials, his office went public with what he learned: Dugway had conducted a test the day before, releasing 320 gallons of the synthetic nerve gas VX (venomous agent X) from a high-speed jet aircraft.2 VX is among the most toxic nerve agents, causing blurred vision, confusion, and, eventually, asphyxiation. Even a small droplet can be fatal to humans.3

During the March 13 test, as the plane ascended, a malfunction caused the jet’s spray tanks to stay open longer than intended. The odorless, tasteless chemical continued to spray at the higher altitude, caught by the wind and traveling beyond the proving ground. On March 21, Senator Moss called for a “thorough investigation” by the Army into a possible link between Dugway and the “mysterious deaths” of 6,000 sheep. In the meantime, veterinarians, scientists, and health officials found that sick, surviving sheep appeared to be suffering symptoms in line with nerve gas poisoning. Further examination of food and water sources in the area, as well as of deceased sheep, confirmed what many already suspected: the presence of VX.4 The Army, for its part, never released a full report or acknowledged responsibility, though it did pay claims to ranchers who lost sheep. Thirty years after the incident, The Salt Lake Tribune obtained a previously classified 1970 report in which Army researchers described evidence of VX in the area as “‘incontrovertible.’”

At first, reactions to the Dugway sheep incident were relatively subdued. That began to change in 1969, when Representative Richard McCarthy (NY) called for congressional hearings. In addition to drawing attention to Dugway, McCarthy exposed plans to transport outdated, and likely unstable, chemical munitions by train to the east coast, where they would be loaded onto ships to be scuttled in the Atlantic Ocean—a practice the Army had dubbed Operation CHASE: Cut Holes and Sink ‘em. Then, in July 1969, reports emerged about nerve gas leaking from munitions stored on a U.S. military base in Okinawa, Japan, sickening more than 20 personnel. And all the while, public opposition to the U.S. military’s use of herbicides like Agent Orange in Vietnam continued to grow.5

Together, these events helped hasten a review of U.S. policies on chemical and biological warfare. On November 25, 1969, President Richard Nixon announced the U.S. would renounce the use of biological weapons, including retaliatory use; cease research and development on offensive biological weapons, but continue research for defensive purposes; and work to eliminate its existing biological weapons stockpile. The statement also affirmed U.S. policy on no first use of chemical weapons, while permitting ongoing chemical weapons research and development.

We may not know for certain whether knowledge of the Dugway sheep incident informed or motivated Dr. Cox’s actions. We can, however, glean from his initial letter to Senator Symington that he was cognizant of evolving CBW policy under President Nixon. We can also contextualize his concerns in the burgeoning public discourse around chemical and biological weapons—not only nationally, but also close to home.

“The public is entitled to know”: St. Louisans call for action

In 1958, three Washington University faculty and two St. Louis citizens created the Greater St. Louis Committee for Nuclear Information (CNI). They were Barry Commoner, professor of plant physiology; Walter Bauer, professor of surgical pathology; John Fowler, professor of physics; Rev. Ralph Abele, head of the Metropolitan Church Federation; and Edna Fischel Gellhorn, suffragist and first vice-president of the National League of Women Voters.6 CNI was perhaps most famous for partnering with the Washington University School of Dentistry to conduct the Baby Tooth Survey, which demonstrated the presence of Strontium 90 in baby teeth as a result of nuclear fallout.

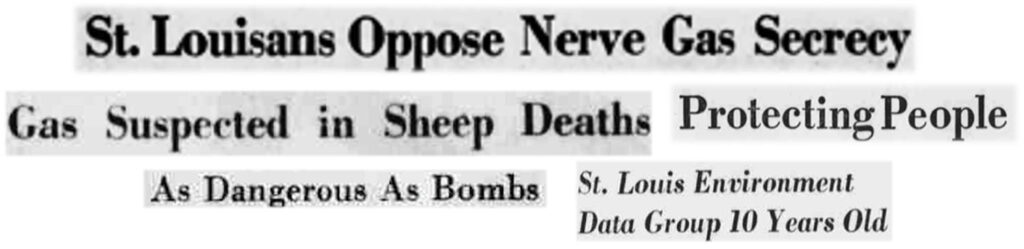

CNI became the Committee for Environmental Information (CEI) in the 1960s, expanding its scope while maintaining its mission of ensuring the public had access to clear, comprehensible scientific information. Indeed, St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporting on the Dugway sheep incident included coverage of a statement released by CEI co-founder Dr. Bauer and Dr. Malcolm Peterson, then the chair of CEI’s scientific division and of the Department of Gastroenterology at Washington University School of Medicine. On March 22, 1968, the two doctors called for a full investigation: “‘The public is entitled to know whether this (nerve gas) is the cause of the animal’s [sic] deaths.’”7 By April, CEI had asked a scientist in Montana to study the incident.8

The following year, in May 1969, two School of Medicine pathologists appeared before Congress on behalf of CEI’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Subcommittee. On May 13, Steven L. Teitelbaum testified before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, and on May 20, Gustave L. Davis testified before the House Committee on Government Operations. Both doctors addressed the issue of continued CBW testing, as well as the proposed rail shipment of surplus mustard gas and nerve gas across the country to be dumped in the ocean. Locally, the Post-Dispatch and KMOX Radio covered the hearings, as did 216, the community publication of the Jewish Hospital of St. Louis. Nationally, Dr. Teitelbaum appeared on Walter Cronkite’s CBS evening news program. Representative McCarthy, who had exposed Operation CHASE, also testified at the hearings and cited the work of CEI.9

CEI members were not the only Washington University faculty working to bring awareness to the dangers of CBW. In March 1969, Milton J. Schlesinger and Sondra Schlesinger, then, respectively, associate and assistant professors of microbiology in the School of Medicine, wrote in a Post-Dispatch letter to the editor that, “We consider the testing and stockpiling of chemicals and bacteriological materials intended as weapons to be every bit as dangerous as nuclear weapons.”10 They urged international prohibitions on testing and the eventual elimination of all such materials.

Perhaps Dr. Cox was aware of CEI’s work; maybe he even interacted with his Washington University colleagues who were members of the group. What we do know is that he lived and worked in a community where his fellow citizens were actively engaged on issues related to chemical and biological weapons. This context helps us better understand the sociopolitical climate within which Cox was so determined to learn the origins of the missile launch.

“I seem to be stumped”: if not from Dugway, then from where?

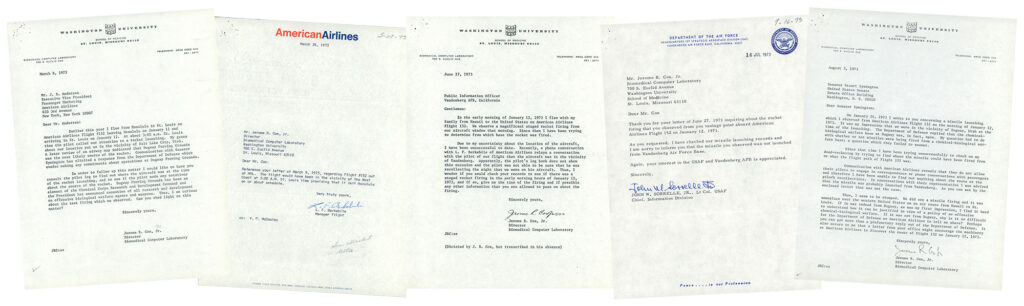

Back to 1973: unsatisfied with the Army’s response to Senator Symington, Dr. Cox wrote directly to American Airlines in March in search of more information. He received replies from a customer relations manager and a flight manager, but when they did not provide any new details, Cox doggedly pursued the matter into April, even requesting to speak directly with the flight’s pilot. Another exchange of letters resulted in a May phone conversation with an airline representative, who relayed the pilot’s recollection that they could have been in the vicinity of Vandenberg Air Force Base at the time of the launch. And so, in June, Cox wrote to the base, asking if they would check their launch records and share as much information with him as allowed.

Selected correspondence between Jerome Cox and American Airlines, Vandenberg Air Force Base, and Senator Symington, March – August 1973.

When that inquiry, too, turned out to be a dead end, Dr. Cox reached out to Senator Symington in August, admitting, “I seem to be stumped.” Frustrated by the lack of transparency, he asked, “If it was not from Dugway, why is it so difficult for the Department of Defense or American Airlines to tell me where?” He wondered if the senator might, once again, attempt to get an answer. Symington did so and promised to keep Cox informed.

At long last, in September, Dr. Cox received word from Senator Symington that it seemed Green River, not Dugway, had been the source of the missile launch. Located in central Utah, the Green River Launch Complex was built by the U.S. Air Force in 1964 for testing missile and projectile weapons. The complex operated in collaboration with the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, a U.S. Army testing facility and firing range established in 1941—and the site of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon in July 1945 (learn more here and here about Washington University’s connections to J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory, which designed the bomb). During the 1960s and 1970s, hundreds of missiles launched from Green River landed in White Sands.

“Glad to have the mystery cleared up” (for the most part)

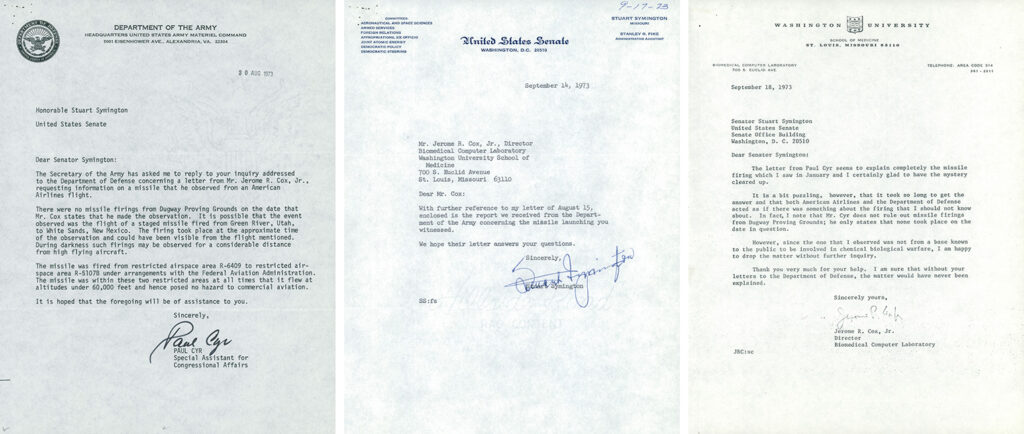

Upon receiving this information from Senator Symington, Dr. Cox was ready to declare the matter resolved—almost. He acknowledged the Army’s response seemed to answer the question of where the launch originated, and he was “glad to have the mystery cleared up.” Still, he expressed some lingering skepticism to Symington, even as he agreed to move forward.

Letters from Paul Cyr to Senator Symington, August 30, 1973; from Senator Symington to Jerome Cox, September 14, 1973; and from Jerome Cox to Senator Symington, September 18, 1973.

“It is a bit puzzling, however, that it took so long to get the answer and that both American Airlines and the Department of Defense acted as if there was something about the firing that I should not know about. In fact, I note that Mr. Cyr does not rule out missile firings from Dugway Proving Grounds; he only states that none took place on the date in question. However, since the one that I observed was not from a base known to the public to be involved in chemical biological warfare, I am happy to drop the matter without further inquiry.”

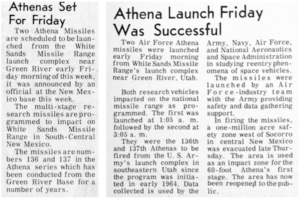

Clippings from The Times Independent of Moab, Utah, January 11 and January 18, 1973, describing the planned, and then successful, launch of two Athena missiles from Green River to White Sands.

These documents help us piece together what happened on the morning of January 12, 1973. Today, with access to additional sources, we can also attempt to corroborate the circumstances surrounding the launch. The Times Independent of Moab, Utah, for instance, reported on the launch of two Athena missiles from Green River to White Sands on January 12, at 1:05am and 3:05am (local time).11 Based on the evidence we have, it seems safe to conclude that Cox and his companions on American Airlines Flight 152 witnessed one of these launches.

What to make of Cox’s ongoing misgivings? By placing the documents in historical context, we can appreciate that his wariness did not exist in a vacuum. On top of the attempted coverup of the Dugway sheep incident, the early 1970s in the United States were a time of revelations about surveillance activities, the covert bombing of Cambodia, and the Watergate scandal. If the question is, as Cox continued to wonder, whether any missile launches took place from Dugway Proving Ground during this period—well, that would require more research.

The end of an archival journey—for now

What have we learned about Jerry Cox from this trip into the archives? While he may not have gotten a definitive answer about the day-to-day activities of a secretive U.S. military facility, we find someone who was discerning, diligent, and determined. We gather he was civic-minded, both from how he pursued the issue of the missile launch with Senator Symington, and from other sources that show he frequently engaged with policymakers about a range of issues. We see that he deeply valued transparency, particularly when it came to how federal resources were being used and to matters of public health. And we learned that his papers not only document his distinguished academic career at Washington University; they also provide insight into how he approached his role as a member of society.

One of the joys of working with archival materials is the chance to follow a thread and see where it leads. What a journey ensued thanks to just a few of the thousands of documents that make up the Jerome R. Cox Jr. Papers.

- Letter from Jerome R. Cox Jr. to Senator Stuart Symington, January 24, 1973, FC157-S06-B015-F01, Bernard Becker Medical Library Archives, Washington University in St. Louis. All subsequent quotations from Cox’s correspondence can also be found in FC157-S06-B015-F01. ↩︎

- Lorraine Boissoneault, “How the Death of 6,000 Sheep Spurred the American Debate on Chemical Weapons,” Smithsonian Magazine, April 9, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-death-6000-sheep-spurred-american-debate-chemical-weapons-cold-war-180968717/, accessed December 17, 2025. ↩︎

- Matthew S. Meselson, “Chemical and Biological Weapons,” Scientific American 222, no. 5 (1970): 18-19. ↩︎

- Boissoneault, “How the Death of 6,000 Sheep Spurred the American Debate on Chemical Weapons”; and Seymour Hersh, “On Uncovering the Great Nerve Gas Coverup,” Ramparts 7, no. 13 (1969): 13-14. ↩︎

- Simone M. Müller, “‘Cut Holes and Sink ‘em’: Chemical Weapons Disposal and Cold War History as a History of Risk,” Historical Social Research 41, no. 1 (155) (2016): 274-75; Meselson, “Chemical and Biological Weapons,” 16, 21-23; and Boissoneault, “How the Death of 6,000 Sheep Spurred the American Debate on Chemical Weapons.” ↩︎

- Jerome P. Curry, “Protecting People, St. Louis Environment Data Group 10 Years Old,” sec. 3G, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 7, 1968. ↩︎

- “Gas Suspected in Sheep Deaths,” sec. 12A, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 22, 1968. ↩︎

- Curry, “Protecting People,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 7, 1968. ↩︎

- William K. Wyant Jr., “St. Louisans Oppose Nerve Gas Secrecy,” sec. 16C, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 21, 1969; and “Hospital Pathologists Testify in Washington,” 216 Jewish Hospital of St. Louis 18, no. 4 (August 1969): 8, https://beckerarchives.wustl.edu/RG025-S09-ss03-B61-F16-i03. ↩︎

- M.J. Schlesinger and S. Schlesinger, “As Dangerous as Bombs,” sec. 2B, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 18, 1969. ↩︎

- “Athenas Set For Friday,” Times Independent, January 11, 1973, Utah Digital Newspapers, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s61g1zd0/20469799, accessed December 17, 2025; and “Athena Launch Friday Was Successful,” Times Independent, January 18, 1973, Utah Digital Newspapers, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6sr0bk0, accessed December 17, 2025. ↩︎