By November of 1917, the original members of Base Hospital 21 were six months into their deployment to Rouen, France. Recruited from the Washington University Medical Center, the doctors, nurses and enlisted personnel who had left St. Louis in May with great fanfare were now settling into a routine that included being severely overworked. When the unit arrived in France to assume control of a British army hospital, it became obvious they were seriously understaffed. A cohort of British personnel remained to help until American medical reinforcements could be sent, but by the start of November, the reinforcements still had not arrived.

The unit’s nurses had been looking forward to a break – a short leave with the opportunity to visit Paris. Louise Hilligass wrote home that November remarking, “I had expected to have my vacation in Paris before this, but something happened to prevent our going, so we have that to look forward to.” Plans changed as the British offensives in Flanders continued into the fall with major battles near Passchendaele dragging into November. Worsening the staff shortages, several advance surgical teams consisting of a surgeon, anesthetist, nurse assistant and orderly were formed and moved forward to the Casualty Clearing Stations. The unit commander, Col. Murphy, other high-ranking medical officers and many of the nurses were also rotated through these stations close to the front.

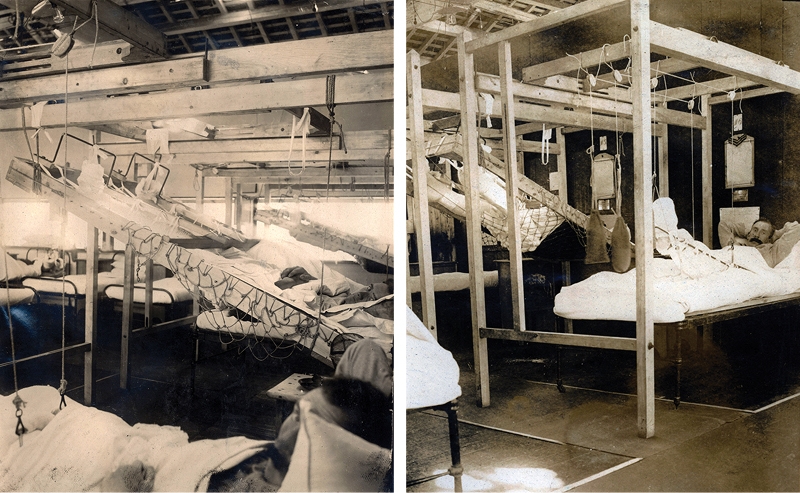

Paris would have to wait for nurse Olga Krieger as well. Krieger, who wrote in her diary of the excitement of going “over there” and her shock at the realities of the war, noted that in early November she was assigned to day duty in Surgical Hut No. 6. The hut was designated for soldiers with serious leg injuries such as fractured femurs and knee joints. “Patients usually remained here for months as clean cases are very rare and bone requires a long time to knit; deaths here were few compared with the dreadful cases they are; hemorrhages were frequent due to secondary causes; the [tourniquet] was the most valuable article in the place, in fact it was most desirable one for a belt or a [lavaliere.]”

World War I brought about a revolution in the treatment of fractures caused by gunshot. New methods, like those devised by British Army Medical Office Major Meurice Sinclair for suspending injured limbs, were rapidly adopted and were a strange sight for nurses trained for civilian hospitals back home. Soldiers in Hut No. 6 recuperated suspended in an array of splints and cables supported by a system of pulleys and framing. Krieger remarked, “The place looked more like a menagerie than a hospital ward.”

Finally, reinforcements arrived on Nov. 15, including 23 additional nurses.

One of these nurses, a graduate of St. Luke’s Hospital Training School for Nurses, later wrote a free-verse poem about her first arrival at Rouen that November.

“Gradually I awaken

And realize that I have arrived in France

At the long-looked-for Base,

…

And that my days of war duty have begun.

Bitter cold room.

Ice-cold clothes.

How can those others laugh and talk?

Why did I come to this place?

How soon may I go home? Will I ever smile again?

Will I ever be warm again?

Who invented war?”

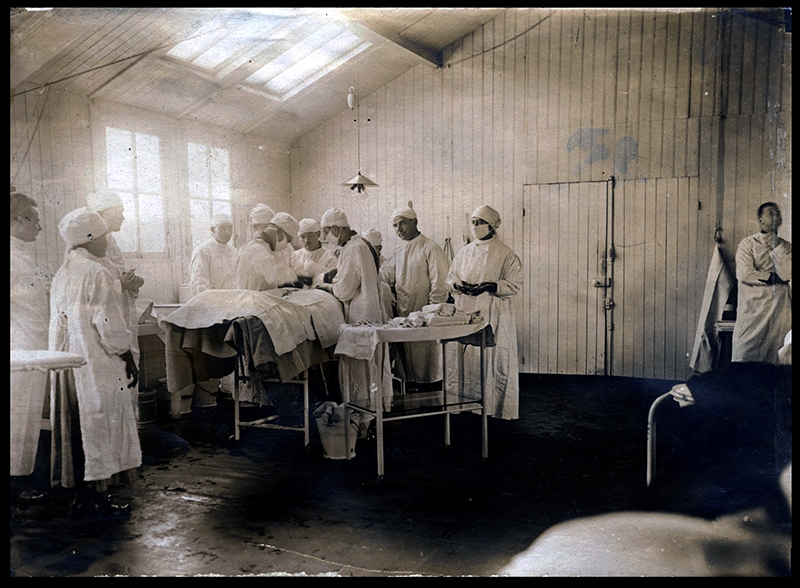

Another November arrival was also eagerly awaited. Levi Fuson, who had only graduated from Washington University School of Medicine two years prior, was one of the unit’s surgeons. He wrote in his diary that while he was at the operating table in the surgical hut “in the midst of [a] group of surgeons and surgical nurses” the adjutant rushed in with a telegram and read it to him. “Wife and son extra fine, born this morning.” The adjutant had also been anticipating the news and rushed into the hut “with no small smile of pleasure on his face.”

The news spread quickly. “Everyone whom I saw extended kind congratulations,” Fuson wrote. At dinner, with the commanding officer away on his rotation to the forward stations, Fuson was “bodily placed in the CO’s chair” at the head table in the mess hall. Though the unit’s dinner service was normally dry, some libations turned up. “The whole mess captains and majors stood and drank a toast to my new boy. You can’t know my appreciation.”

That Thanksgiving the unit gratefully celebrated all the new arrivals. Hilligass wrote that she and her fellow nurses welcomed their new comrades with a splendid dinner. “It was lovely and everyone enjoyed it so much. The last party we had [it was] the night before we left St. Louis. We were all in our gayest clothes and at this place we were all in uniforms 6 months to the day. [I] wonder where we shall be next 6 months from now.”