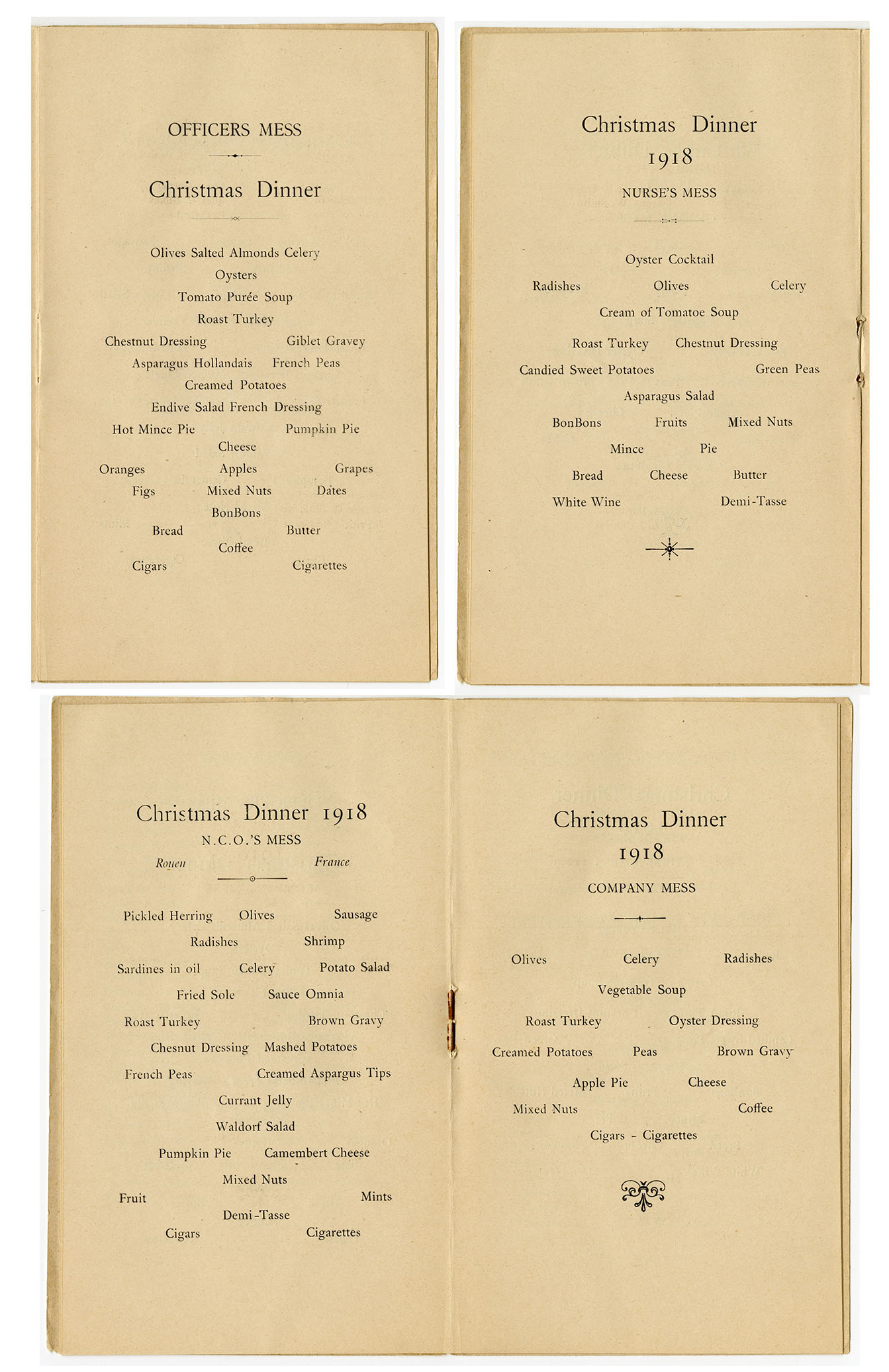

What makes a good memory? How about a good meal? For members of the Washington University medical center who served with Base Hospital 21 during the First World War, special dinners were an important part of maintaining morale for the unit’s doctors, nurses, and enlisted men who were often overwhelmed with the wounded soldiers streaming daily into the hospital. The Base Hospital 21 staff were among the first Americans to land to France in April 1917. After the war ended with the Armistice of November 11, 1918, the work of the hospital continued with wounded and sick soldiers and war refugees still needing care. However, by the end of 1918, the hospital staff were able to enjoy a special Christmas dinner to celebrate the end of the war and the prospect of going home.

During the Second World War, the US Army medical reserve unit at the Washington University medical center was again called into service as the 21st General Hospital. The unit served in three theaters, North Africa, Italy, and France, from October 1942 until September 1945. Most members of the unit, including its commanding office, Col. Lee D. Cady, (WUSM MD 1922) served overseas continuously for almost 3 years. Cady made a special effort to ensure the meals for his hospital’s patients were the very best, even in difficult circumstances. He encouraged the cooking staff to be innovative often to the vexation of the US Army dieticians who more interested in following army dietary regulations than making meals palatable. Cady would occasionally eat in the messes to meet and mingle with his personnel and the wounded soldiers under his care, but also to make sure the kitchen staff did not revert to old ways. Soon the 21st mess halls became a standout among others in the entire North African theater especially for its daily servings of fresh baked goods and pies. Inspectors and visitors from the HQ and other units would ask Cady how was it possible to serve cakes and pies everyday without “some sort of hanky-panky?”

Shortly after becoming operational in North Africa, Cady noticed that the kitchen staff was routinely throwing away grease and fat from every meal service and using all the available butter for baking. He asked why the cooks were not using the leftover lard for baking. If they would, that would also free up butter to serve along with the fresh bread. He wanted cake or pastry every day in every mess. The mess staff accepted the challenge. They eventually became so efficient at the recycling of fat and oil – rendered fat was used to fry donuts, then used for baked goods, and what wasn’t able to be used for food products was turned into soap to wash dishes – that the army command sent other unit’s personnel to the 21st to learn how to run their messes.

By the time the unit relocated to a multi-hospital complex near Naples, Italy, the 21st’s cooking staff had come into their stride. They began making their own pasta. Stuffed ravioli became a frequent item on dinner menus. Their daily baked goods had become the envy of nearby units. So much so that when the mess sergeant noticed they were running out of food at meals, he checked the credentials of everyone leaving the mess tent just at one lunch service and found 138 men were from other units in the camp complex who preferred to eat at the 21st. Many were detained by MPs for being AWOL from their assigned posts.

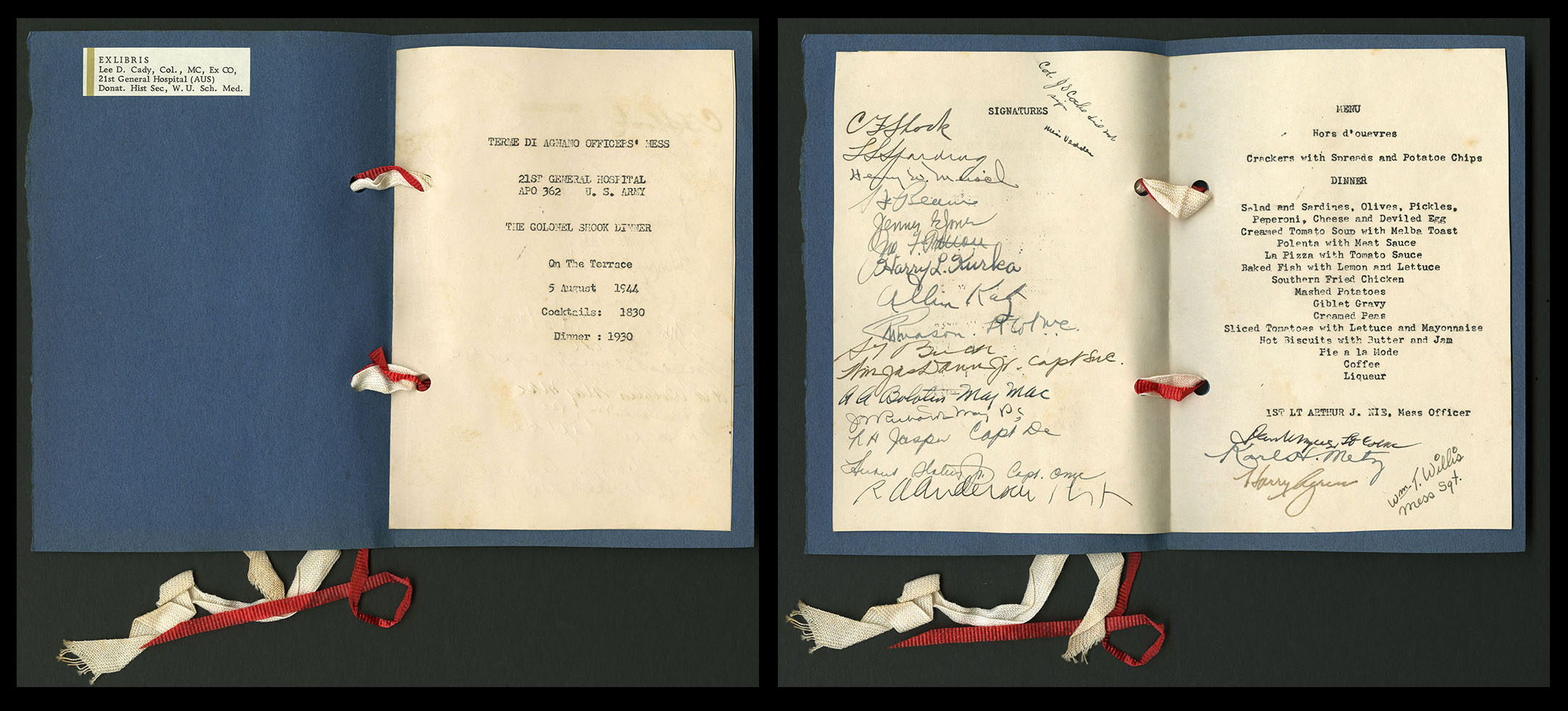

In addition to the daily mess service, the 21st hosted special dinners for visiting top brass and other dignitaries. Cady remembered one dinner for the visiting Col. Charles Shook. “The Shook dinner on the terrace was a great success except for one well-meant but misguided liberty Sgt. Willis took with the generous menu. He was so proud of recent mess resources that [he served] the guests, already stuffed to the gills, with pie a la mode, followed by an unscheduled big piece of heavily iced cake, a double desert. That sort of thing could backfire.” Cady later told his mess sergeant not to overrule his judgment and sensitivity in the diplomacy of menus for selected guests. It was wartime and other units were still envious and distrustful of 21st’s kitchen miracles.

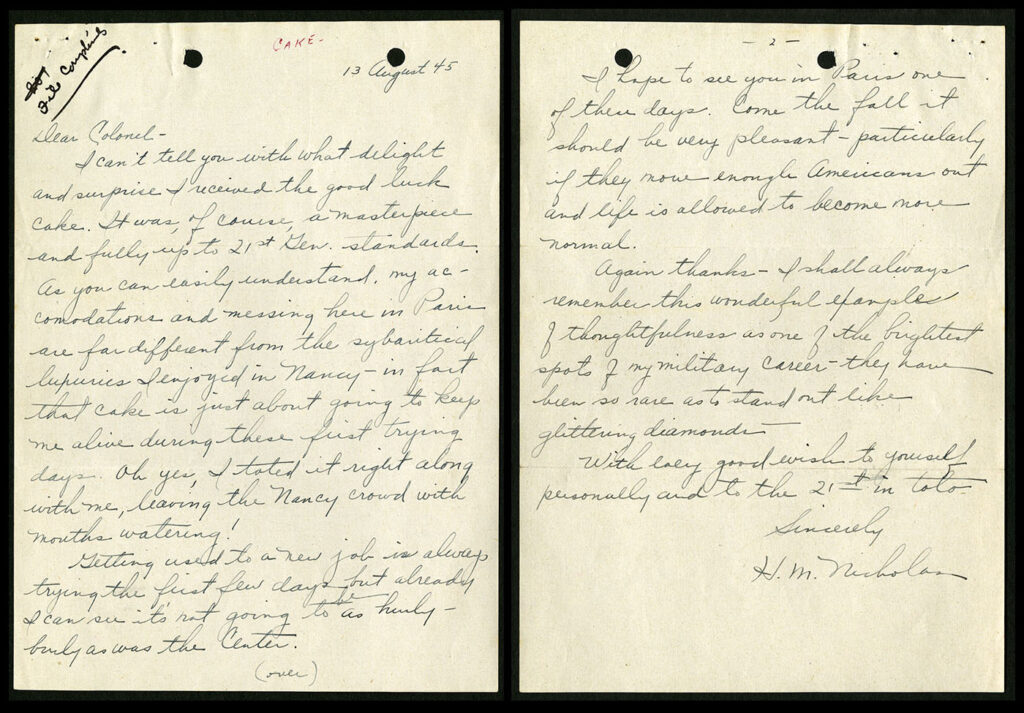

The mess staff were proud of their cakes. They had scavenged enough materials to have multiple ovens for baked goods and their cakes plentiful and legendary. They began making extra, surprise cakes for patients, hospital personnel, and visitors for birthdays or other special occasions.

Cady had a form written up, a fake medical record by a fictitious “Cake Board,” to be presented along with the cakes. The record stated the recipient was a congenital “cake-ivore” with a condition that was “EPTAD”, that is, “Existing Prior To Active Duty.” The Cake Board then recommends that the “subject be classified as hopelessly incurable” and that “a single massive dose of specially compounded cake – 21st GH formula – be administered as a palliative therapy.” For many of the recipients this silly and simple gesture would be a highlight of their difficult wartime experience.

One recipient of the Cake Board’s prescription was Warrant Officer H.M. Nicholas, who was visiting the 21st while being transferred to a new unit. In a letter he later sent to Cady thanking him for the cake, he wrote, “I shall always remember this wonderful example of thoughtfulness as one of the brightest spots of my military career – they have been so rare as to stand out like glittering diamonds.”