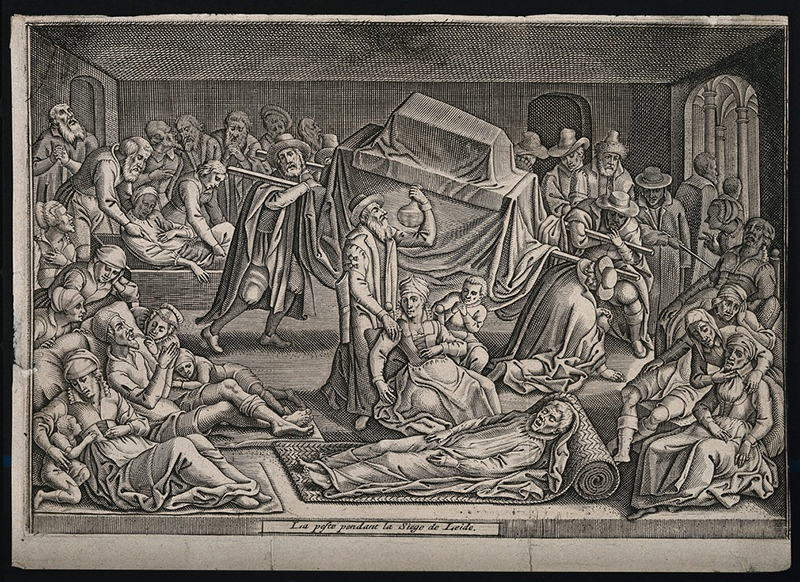

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19 virus) has been a constant fixture in headlines ever since the first cases appeared in Wuhan, China in late 2019. This is the most widespread disease outbreak that most of us have experienced, but epidemics have always been part of the human experience. One of the most famous diseases to wreak havoc on human populations is plague. While the initial outbreak in the mid-14th century, commonly referred to as the Black Death, is the most famous occurrence, the plague lingered in Europe for the next several centuries. Outbreaks often had very high mortality rates—the 1665 outbreak in London killed around fifteen percent of the city’s population, while the death toll in the 1679 Great Plague of Vienna numbered in the tens of thousands—which made plague one of the most feared diseases in early modern Europe.

COVID-19 virus and plague are very different. COVID-19 is a virus spread primarily through respiratory droplets that are released when we cough and sneeze. Plague is a bacterial infection, not a virus, that is spread through the bite of infected fleas. But early modern Europeans wouldn’t have known the difference between these two types of infection. They also didn’t understand the root causes of epidemics. While punishment from an angry God was always seen as a possibility, one of the most common explanations for disease outbreaks was “foul miasmas,” or a corruption in the air that was brought on by unseasonable weather or by the corruption given off by rotting fish and corpses. When people inhaled this foul air, it was believed to cause corruption in their humors—the four fluids that people believed governed the body—and primed the body for plague to take root.

The best measures to prevent COVID-19 are to make sure that you cough and sneeze into the crook of your elbow, stay home if you’re sick, stop touching your face, and perhaps most importantly, wash your hands often and thoroughly. Early modern advice for preventing plague was somewhat different. Because corrupt air was seen as a cause, people believed that purifying it would help drive the sickness away, and many preventive measures were based on this theory. For example, the city of London burned fires in the streets, and medical practitioners recommended burning fragrant substances such as amber, frankincense, myrrh, and juniper berries inside the home. These were not effective, but they actually seem logical in comparison to certain other remedies. Jan Baptist van Helmont, a respected scholar who is seen as the founder of pneumatic chemistry, wrote about crafting preventive amulets out of toad carcasses; while the 16th-century surgeon Ambroise Paré mentioned that plague sores can be cured by enclosing the victim in “the body of a mule or horse that is newly killed, and when it is cold let him be laid in another, until the pustles and eruptions do break forth.”

However, some early modern measures against the plague make sense even today. English officials tried to limit public gatherings, such as when the king issued a decree that no one living in the city of London should attend the 1665 Howden Fair, or any other fairs in the county of York in order to “stay the further spreading of the great Infection of the Plague.” Surgeons recommended washing the house with vinegar and cleaning the linens every day. That advice is similar to current recommendations to practice social distancing and regularly disinfect objects that we use every day, like cell phones and tablets.

We do, of course, recommend getting information on how to protect yourself from the CDC, not medical texts that are hundreds of years out of date!

Sources

Paul Barbette. The Chirurgical and Anatomical Works of Paul Barbette. London: Printed by J. Darby, 1672.

Jean Baptiste van Helmont. Oriatrike, or Physick refined. London: Printed for Lodowick Loyd, 1662.

Ambroise Paré. The works of that famous chirurgeon Ambrose Parey. London: printed by Mary Clark, 1678.

The Newes Published for Satisfaction & Information of the People. Thursday September 7, 1665. London: Richard Hodgkinson, 1665.