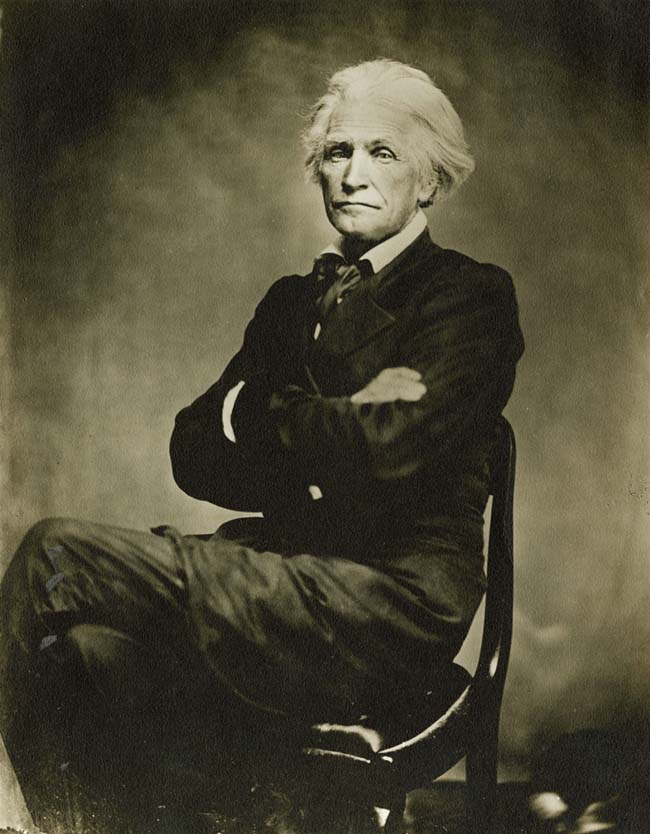

Dr. Joseph Nash McDowell, featured in the portrait below, was born in Lexington, Kentucky in 1805 and he received a medical degree from Transylvania University in 1825. Prior to moving to St. Louis in 1839 with the intention of founding his own medical school, McDowell served as an anatomy professor at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and at the Medical Department of Cincinnati in Ohio.

McDowell arrived in St. Louis with a reputation. He was a brilliant anatomist, an enthusiastic teacher, and an entertaining public speaker. According to his students, he was very boisterous, opinionated, and feisty. He was also notorious for having a persistent fiery temper. He was the kind of person who made enemies easily, and he would regularly ridicule his adversaries in open letters he published in newspapers.

As recounted in James Wilson’s biography of McDowell that was published in the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society (Volume 68, Issue 4, October 1970, pages 341-369), he stirred up trouble in St. Louis shortly after his arrival when he learned that St. Louis University was planning to begin their own medical school. McDowell was jealous and paranoid in nature, and he feared the formation of another medical school would be detrimental to his own grand plans. He delivered numerous inflammatory public speeches against Catholics and the Jesuits at St. Louis University in particular.

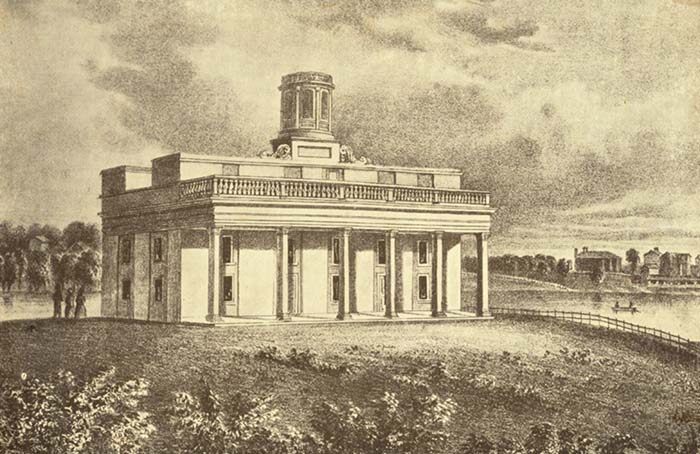

McDowell joined the faculty of Kemper College (featured in the above drawing) in 1840, an Episcopalian school that had opened in St. Louis in 1837, just three years before his tenure began. McDowell developed a medical school curriculum and began offering classes in the summer of 1840, which made the Medical Department at Kemper College the first medical school in operation west of the Mississippi River. However, Kemper College struggled financially, and it went bankrupt five years later.

Nonetheless, McDowell strategically overcame this setback. Without any interruption to course instruction, he could realign his medical school with the University of Missouri in 1845, just months after Kemper College went bankrupt. Shortly thereafter, and largely at his own financial expense, McDowell began constructing a massive new building in downtown St. Louis to house his very own medical school, which is featured in the drawing below.

McDowell’s new building was utilized by University of Missouri medical students beginning in 1850. However, he formally severed ties with the university in 1857 to privatize his medical school under the new name of Missouri Medical College. McDowell’s school included one of the largest anatomical museums in the country and one of the largest museums of natural history, both of which he curated himself.

Strangely, the new medical school also featured a massive collection of Revolutionary War-era weapons. As Estelle Brodman recounts in the article titled, “The Great Eccentric” (Washington University Magazine, Volume 51, Issue 1, Pages 6-11), this arsenal included 1,400 muskets and four cannons he purchased for an expedition he had been organizing since he was a teenager. McDowell planned to lead a private army to the Pacific coast to seize land in northern California. Despite years of hoarding gunpowder and enlisting his students to help keep his arsenal regularly maintained so he could one day set out on his journey to California, he never embarked on what would have been a strange but monumental expedition.

W.B. Outten’s account below of McDowell (taken from the Medical Fortnightly, Volume 33, Issue 6, March 1906, pages 143-146) is especially captivating. It demonstrates the kind of legendary reputation McDowell maintained throughout his lifetime. Dr. Outten, who is featured in the photograph above [LEFT] and who would later become a prominent St. Louis physician himself, first met McDowell in 1859 when he was a teenage student at the Christian Brothers’ Academy. At the time, the academy was located next door to McDowell’s school in downtown St. Louis, as depicted in the drawing above [RIGHT]. Outten claimed,

“We students looked upon Dr. McDowell as a dangerous and evil man, and we had been brought to believe that the doctor was in league in some manner with his Most Satanic Majesty, and if close search would be made about his premises there could have been found a direct passageway between Dr. McDowell and the nether region of Hades.”

The reason Dr. Outten recounted feeling so uneasy around McDowell, as did many other St. Louisans, was that McDowell was widely rumored to be a resurrectionist who frequently removed corpses from local cemeteries. At the time, there were very few legal means to procure cadavers for instructional purposes at his medical school, so he allegedly resorted to stealing them.

McDowell’s connection to alleged nefarious activities in the city’s cemeteries was not a well-kept secret. His school was regularly searched by family members who had discovered a loved one’s tomb was empty. On occasion, McDowell would personally give a tour of his school to these families to pacify their suspicions that he had stolen their relatives’ bodies for dissection.

As Robert Schlueter details in his biography of McDowell in the Washington University Medical Alumni Quarterly (Volume 1, Issue 1, October 1937, pages 4-14), on more than one occasion, angry mobs forced their way into the school in an attempt to catch McDowell red-handed when he was suspected of stealing a body. Fearing for his life, he resorted to hiding within the school in creative ways to avoid these mobs. On one occasion, he hid in a chimney. On another occasion, he laid on a dissection table and covered himself with a sheet to avoid detection.

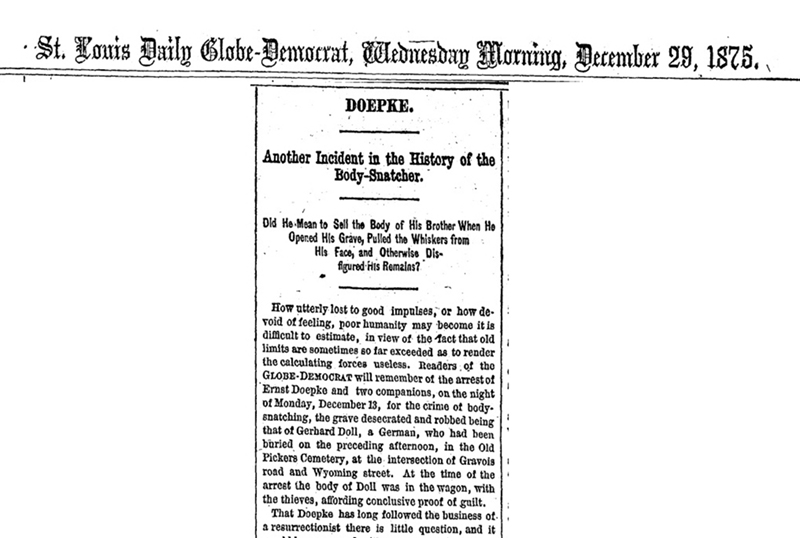

While McDowell was never convicted of grave-robbing, one of his employees was caught in the act of pilfering cemeteries – three times! As described in the Dec. 29, 1875 issue of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat (page 4) featured above, Ernest Doepke, who McDowell paid to “manage his mortuary”, was caught with a body in his wagon that police identified as Gerhard Doll. Upon further investigation of Pickers Cemetery, where Mr. Doll had been interred the day before, more bodies were discovered missing. The Globe-Democrat journalists assailed Doepke for his lack of respect for the dead and criticized those medical schools (as far away as Indianapolis) that purchased these bodies from him since they were obtained in such a disgraceful manner.

Conversely, McDowell was far more conscientious with the bodies of his own deceased loved ones. When his teenaged-daughter passed away unexpectedly, he created a custom tube-shaped coffin lined with copper. After placing her body in the cylindrical-shaped coffin, he then filled the copper tube with alcohol and sealed it shut. Her coffin was then deposited in a vault on the grounds of his medical school for safekeeping, but it was later moved to a cave he purchased near Hannibal, Missouri.

As recounted by K. Patrick Ober in “The Body in the Cave” (Mark Twain Journal, Volume 41, Issue 2, Fall 2003), a rumor that children had been secretly entering the cave, which is now known as Mark Twain Cave, and daring each other to open the copper tube to view the body would later serve as the inspiration for the grave robbing story in Twain’s classic Tom Sawyer novel. Norman Rockwell illustrated this famous scene with Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher (below) in 1936.

Several additional copper tubes were crafted for McDowell’s other family members. As Luke Ritter recounts in his piece titled, “Anatomy, Grave-Robbing, and Spiritualism in Antebellum St. Louis” (The Confluence, Spring/Summer 2012, pages 34-46), McDowell felt normal burial customs smothered the soul after one’s demise. Upon the death of his first wife, Amanda Drake McDowell, an alcohol-filled copper coffin was created to house her body, which was laid to rest inside one of the Cahokia Indian Mounds in Illinois. With the aid of a rudimentary telescope, McDowell could view her burial mound across the Mississippi River from the top of his medical school. McDowell insisted that his body should be placed inside one of these custom copper tubes when he died as well, and he had apparently made arrangements in advance to have his coffin interred in Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave. Ultimately, these plans for his own body never came to fruition.

In his commencement address to his Missouri Medical College students in 1861, McDowell informed everyone he would be taking a sabbatical as Dean of the school to offer his services to the Confederate Army. The school closed shortly after the outset of the Civil War, and McDowell fled the city to serve as a doctor in the confederate army. He was eventually promoted to Surgeon General of the Confederate Army of the West during the war.

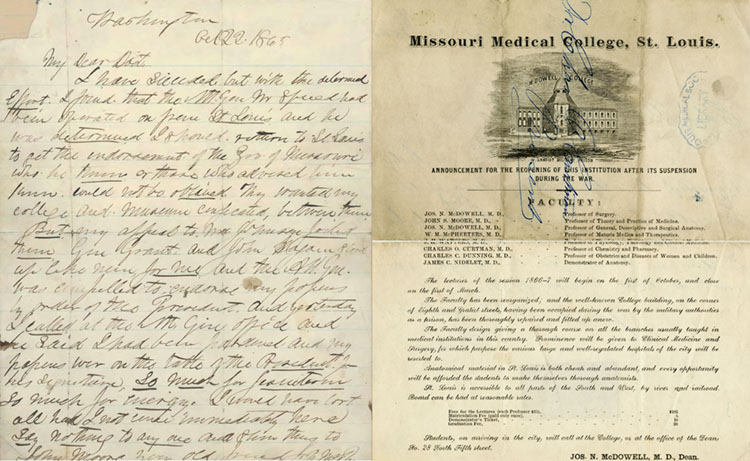

As described in an earlier blog post, the Union Army used his school as a military prison for the duration of the war. When the fighting ceased in 1865, he was granted a pardon for his service with the confederate army by President Andrew Johnson. This pardon, which McDowell describes in the letter below [LEFT], allowed him to return to St. Louis to resume his position as Dean of the Missouri Medical College. Also featured below [RIGHT] is the announcement for the medical school’s reopening after its suspension during the war.

In 1868, McDowell died suddenly at the age of 63, but his school continued to operate for 31 years after his death before it was absorbed into Washington University’s medical department in 1899. Despite his many eccentricities and off-putting temperament, McDowell was fondly remembered by his students as a remarkable teacher. He was revered by the medical community in St. Louis, and beyond, for many decades after his death. In fact, members of the St. Louis Medical Society purchased a new gravestone in 1942 and held a special ceremony in Bellefontaine Cemetery to honor McDowell’s memory. A photograph of this occasion is below.

There was an unexpected resurgence of curiosity into the life of McDowell in 2012 after the release of the cult movie Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, where he made an appearance as a blood supplier. Viewers were surprised to learn that the outlandish character in the movie was based on a real person. For having such a fascinating life, the legend of Joseph Nash McDowell is likely to persist well into the 21st Century.