Throughout the duration of the Civil War, 1861-1865, the city of St. Louis avoided battles and significant violent conflicts. Due to its strategic location on the Mississippi River, it was considered a vital city to the Union for its steamboat ports and shipping commerce.

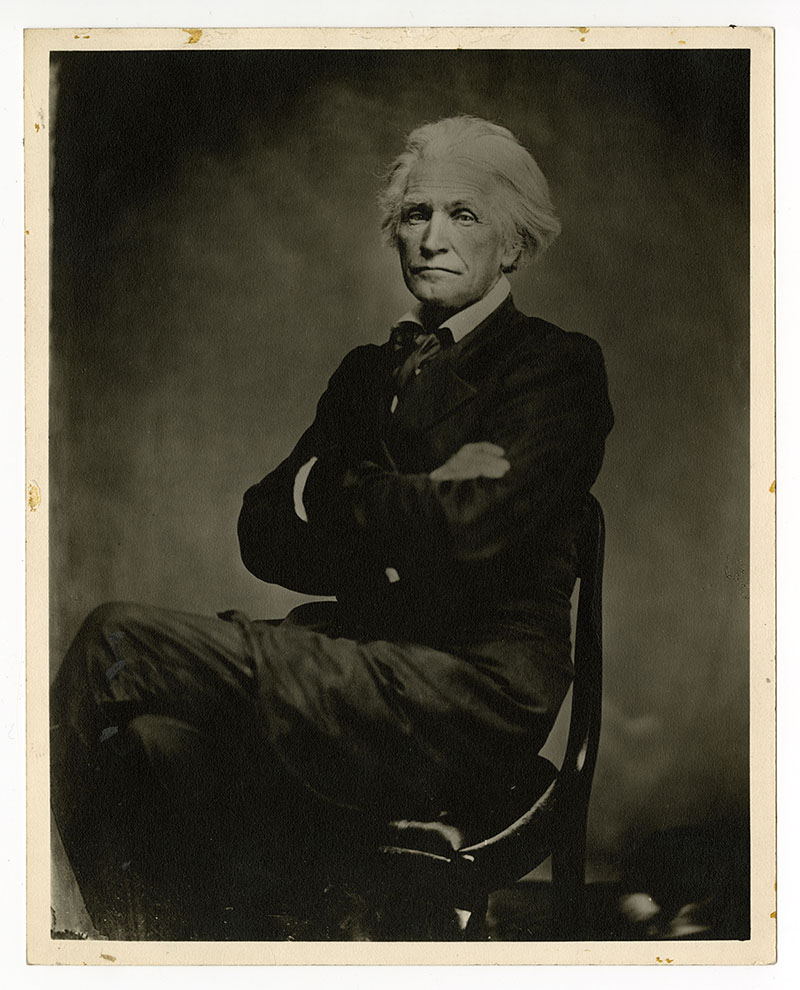

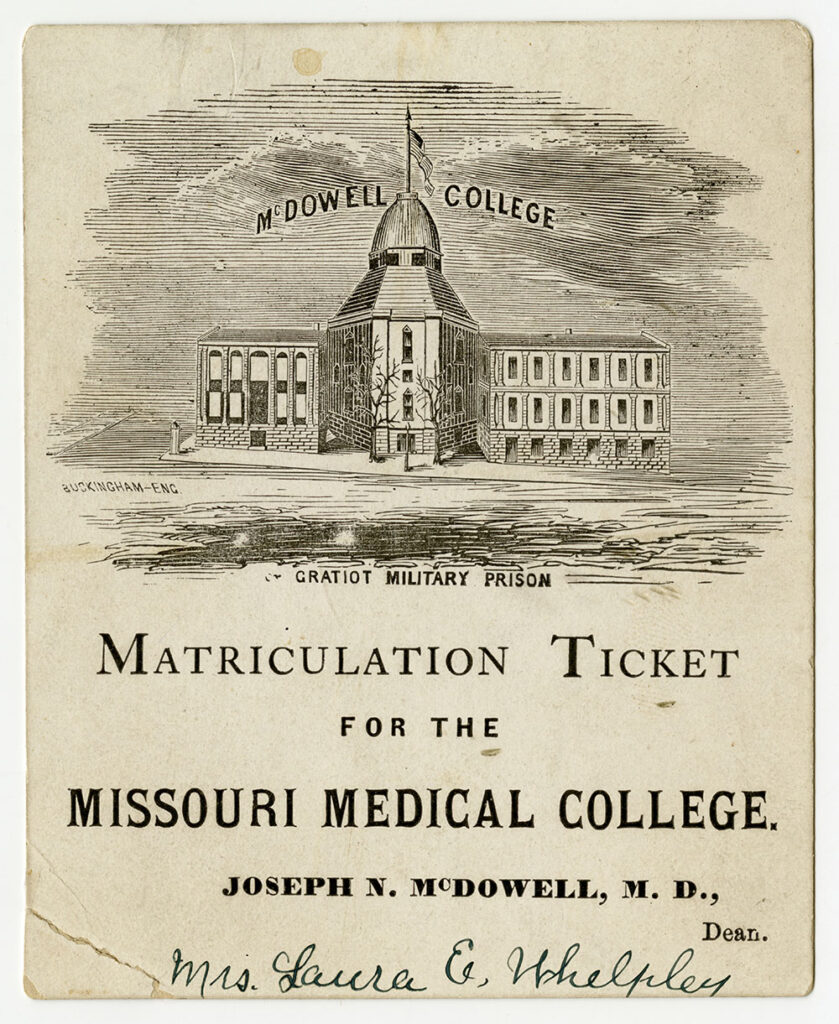

Some of the city’s noteworthy imports during the war included Confederate sympathizers, spies, and soldiers captured and sent north via steamboat as prisoners of the Union Army. To accommodate these new arrivals, the Union Army seized control of the Missouri Medical College in 1861 (just 5 weeks after the war began) so that it could be remodeled to serve as a military prison. The school had closed at the outset of the war, and its dean, Dr. Joseph Nash McDowell, had fled the city to serve as the Surgeon General of the Confederate Army of the West.

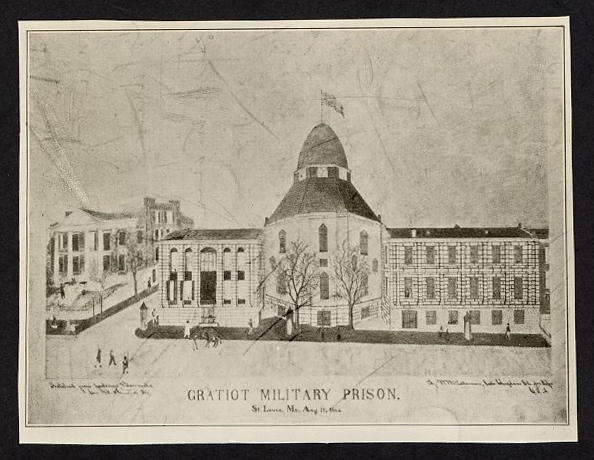

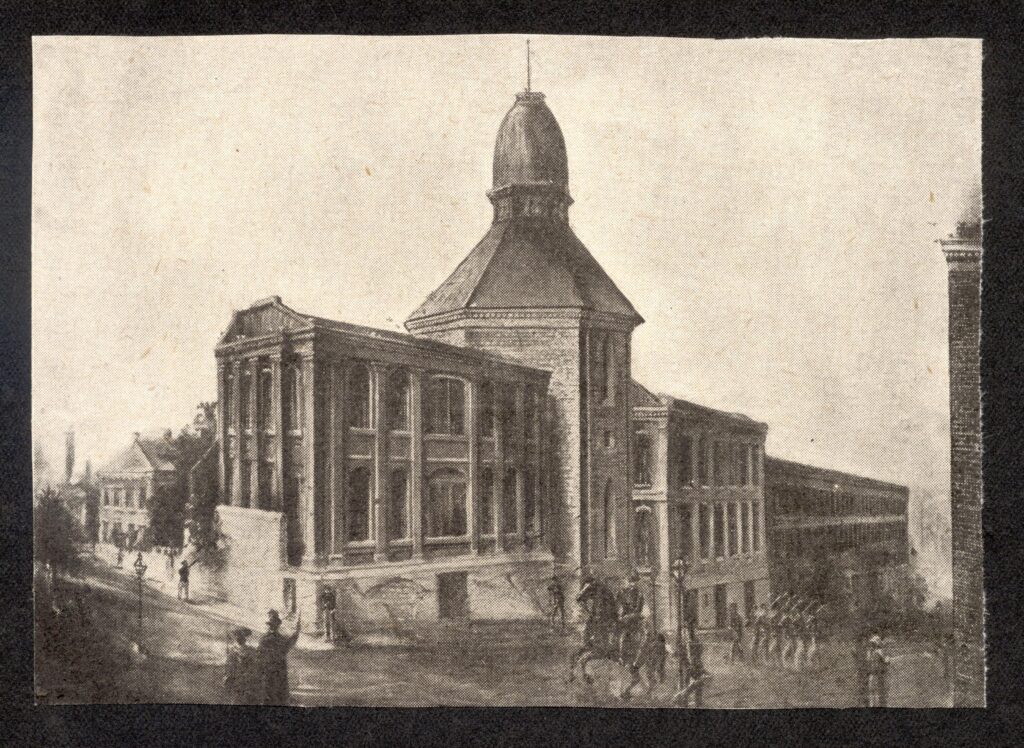

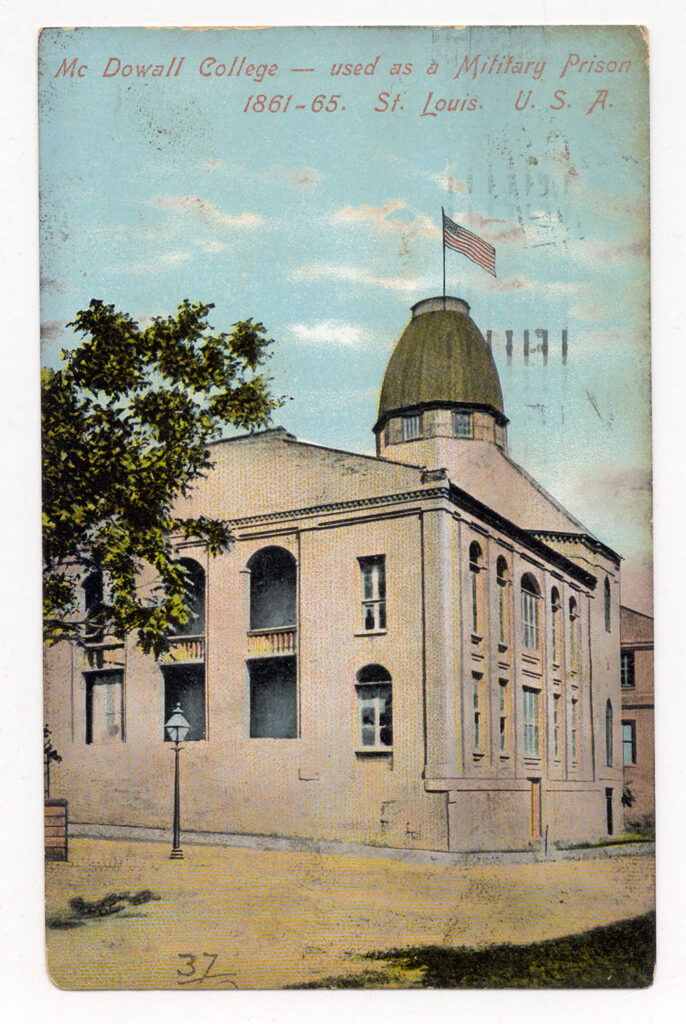

The Missouri Medical College building, more commonly known at the time as McDowell’s College, stood at the corner of Eighth and Gratiot streets in downtown St. Louis. The Union Army renamed the massive building with its distinctive octagonal dome the “Gratiot Street Military Prison,” although locals sometimes referred to it as “McDowell’s Prison.” The building no longer stands today, and currently, this location now serves as the Nestle Purina corporate headquarters.

Ongoing renovations to McDowell’s building were needed throughout the war to accommodate the 1200 to 2000 inmates that could be kept there at any one time. Each time the building was remodeled, new skeletons and anatomical specimens were discovered that had been used for dissection and class instruction for medical students.

Dr. McDowell was a notorious grave robber who frequently removed corpses from local cemeteries to provide cadavers to his students for dissection. Of course, this practice was illegal, so he took measures to bury and hide cadavers throughout his building once they were no longer useful for instruction. Inmates often described the prison as dark and creepy, and its reputation for being haunted grew with each discovery of human remains.

Most of the Confederate soldiers who were held at the Gratiot Street Prison were only detained there temporarily as they awaited transfer to prisoner of war camps. The prison was primarily used to confine Southern sympathizers accused of acts that supported the Confederacy (such as providing weapons and food supplies to southern states), political prisoners and Union Army soldiers who had deserted their regiments or disobeyed orders.

At the conclusion of the war in 1865, McDowell returned to St. Louis where he resumed his position as dean of the Missouri Medical College. Classes resumed the following year, even as the building underwent significant repairs and renovations to convert it back into use for medical instruction.

Dr. McDowell remained a stalwart defender of the Confederacy even after the war. According to legend, one new addition to his school included an eerie room know as “Hell,” which included snakes, alligators and an effigy of Abraham Lincoln hanging from the ceiling. In 1868, Dr. McDowell died suddenly at the age of 63, but his school continued to operate for 31 years after his death when it was absorbed into Washington University’s medical department in 1899.