If you look through the Katherine Bain Papers, held at Becker Archives and Rare Books, you’ll find records of Katherine “Kitty” Bain, MD’s work with the Children’s Bureau and UNICEF, as well as materials that document her love for her family, friends, and dogs. But if you look closer, sprinkled throughout the collection are traces of one friend in particular, Ms. Christine Glass.

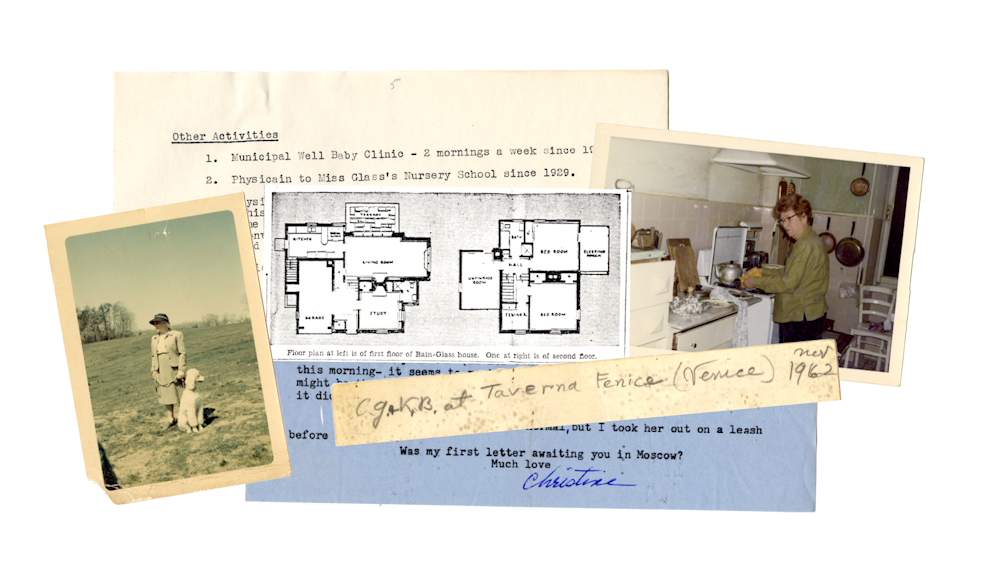

There are newspaper clippings from the 1930s about the nursery school Glass ran in St. Louis, where Bain worked as a pediatrician until 1940. Photocopies of an article from 1949 on the unique architecture of the “Bain-Glass house” in northwest Washington D.C. Newsy letters of home sent to Bain while she was on a business trip to Europe and the Soviet Union in 1960, signed “Much love, Christine.” A photo of the two women at a restaurant labeled “C.G. and K.B. at Taverna Fenice (Venice), Nov. 1962.” And in the Bain Banner, a family newsletter produced in honor of Bain’s 100th birthday in 1997, memories from family and friends of visiting Kitty and “her friend Miss Glass” at the house on 2710 Quebec Street.

Reconstructing people’s lives using archival records is difficult. Trying to determine if a friendship between two women was something more can be even more challenging. It would not have been safe for Bain and Glass to be open about a romantic relationship while they were both alive, and at first glance the records we have are rather ambiguous, perhaps intentionally so. What can we learn if we look closer?

Traces of Two Lives Intertwined

By combing through Bain’s papers and putting together the sprinkled traces with searches in digitized newspaper archives and forays into databases of government records, some more details of these two women’s lives become clear.

Bain worked as a staff physician at Glass’s Progress Pre-School in St. Louis beginning in 1927 or 1929. In 1940, Bain took a position in Washington, D.C. at the Children’s Bureau, then part of the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. A newspaper article from September 1940 about Bain’s new position mentions that Bain had been living at the preschool; the school ceased operations the following year in 1941.

When Bain first moved to Washington, D.C., she lived in an apartment on Porter Street, and Glass later joined her. In an anecdote in the Bain Banner newsletter, Henry Work, a colleague of Bain’s, mentions staying with Bain and Glass in that apartment when he first joined the Children’s Bureau in 1947. Despite initial difficulties finding a bank who would give two unmarried women a mortgage, in 1949 Bain and Glass pooled their money to build the house at 2710 Quebec Street, in northwest D.C. According to the building permit, the house was jointly owned by Bain and Glass.

In another memory from the Bain Banner, former neighbor John Hutchins remembers his family being invited by Bain and Glass to come for Thanksgiving dinner in 1974, the year after the Hutchins family moved to Quebec Street. Glass died in 1977, and is remembered in her obituary as “daughter of the late Frank P. and Mattie Purnell Glass; sister of Louise Glass Marzoni and friend of Katherine Bain.”

All these pieces together, photos and articles and letters and memories, show that for more than 40 years, Katherine Bain and Christine Glass shared their lives with each other. There are no diary entries or Valentines or recordings of conversations that say in their own words how exactly these two women identified or defined their relationship in private, but the documentation we do have may indicate that Kitty and Christine were a couple, a couple who loved each other very much.

It is also clear that they loved their home at 2710 Quebec Street. Just as the materials scattered through the collection directly and indirectly illuminate Bain and Glass’s lives together, the letters and photos and memories of their house shed light on their relationship as well.

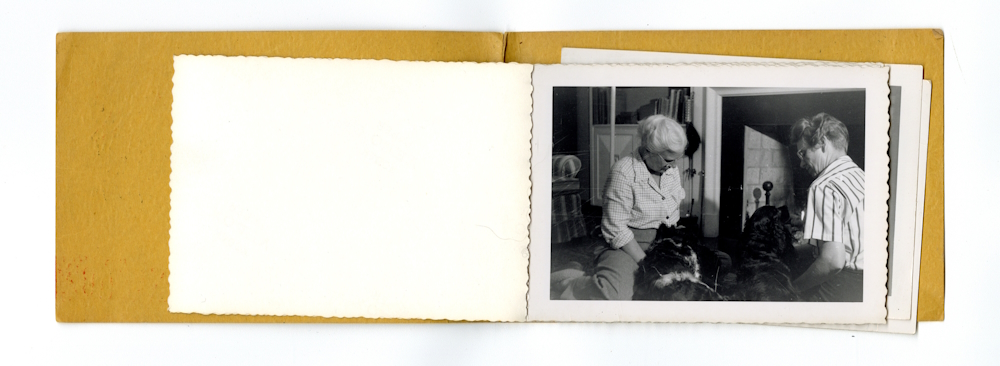

The collection holds many, many photos of the house, its garden, the series of beloved dogs it housed, and the family and friends who gathered there: a slim book of snapshots showing the interior and exterior of 2710 Quebec. 35mm slides from the ‘60s, many of the exterior of the house, some of its gardens in bloom, and one, labeled “Home,” of Glass seated on the porch steps with two placid dogs. An undated photo of Bain cooking in the kitchen, holding a pot with a bright yellow potholder. Glass’s newsy letters to Bain in 1960 are full of details about their home, too—the front lock that was sticking, the never-ending work of raking leaves, a question on the whereabouts of the address book, the gutters Bain’s nephew Patt cleaned, the white camelia that was about to bloom. Traces of two lives, intertwined, rooted at the home they built together.

Kitty, Christine, and Challenges Identifying LGBTQ+ Voices in the Archives

What we know of Bain and Glass’s lifestyle fits a pattern followed by many sapphic women at the time, though it was a type of relationship that was increasingly under suspicion as prejudices against same-sex attraction flared in the years following World War II.

Bain and Glass would have had particular reason to be worried about publicizing their relationship because Bain worked for the federal government during a time when thousands of queer federal employees were fired or forced to resign from their jobs due to their sexuality. The Lavender Scare, tied to the anti-communist Red Scare, lasted from the late 1940s through the 1960s, nearly the entire time Bain worked for the Children’s Bureau. The panic led to two congressional investigations and laid the groundwork for an executive order from President Eisenhower in 1953 that made it legal to include sexuality in the criteria used to decide if a person was fit to work in the federal government. At least 5,000 gay people lost their jobs during the Lavender Scare, though historians estimate the number may be in the tens of thousands. Bain was not free to openly share her relationship with Glass, and the ambiguity in her papers reflects that.

That ambiguity, in Bain’s papers and in many others, can make it difficult to identify LGBTQ+ voices in the archives. Archivists must also consider the ethics of posthumously identifying queer people who were not open about their sexuality during their lifetimes. It’s a balancing act between “respecting evolving community vocabularies, respecting the intentional ambiguity of historical LGBTQIA+ experiences, and facilitating research into queer histories,” as Alexandra deGraffenreid and Gideon Goodrich put it in an article about improving access and discoverability of queer collections in archives.

For these reasons, in the description for the Bain Papers I identify Glass as Bain’s “longtime friend and housemate,” a coded euphemism for a lesbian relationship, in order to respect Bain and Glass’s right to self-identify and recognize that it seems neither woman openly identified as a lesbian during their lifetimes. At the same time, I indicate in the collection description that Bain and Glass owned a house and lived together for at least thirty years, in order to provide further information about their relationship as we understand it for researchers.

Katherine Bain’s papers trace her career and personal life; the life she led. Sprinkled throughout her papers are also traces of her relationship with Christine Glass. In many of those documents, Bain and her friends and family refer to Glass as Bain’s friend. But as we have seen, she was also likely much more.

References

Adkins, Judith. “‘These People Are Frightened to Death’: Congressional Investigations and the Lavender Scare.” Prologue Magazine 48, no. 2 (Summer 2016). https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2016/summer/lavender.html

deGraffenreid, Alexandra and Gideon Goodrich. “Improving Access and Discovery of LGBTQIA+ Materials Across Collection Services Workflows.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies 10, article 18 (2023): 1-15.

Rupp, Leila and Susan K. Freeman. “Episode 5: Romantic Friendships: Boston Marriages (part 2).” Produced by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Queer America. November, 14, 2018. Podcast, MP3 audio, 46:28. https://www.learningforjustice.org/podcasts/queer-america/romantic-friendships-part-2-boston-marriage

Weeks, Linton. “‘Female Husbands’ in the 19th Century.” NPR History Department. NPR, January 29, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/01/29/382230187/-female-husbands-in-the-19th-century