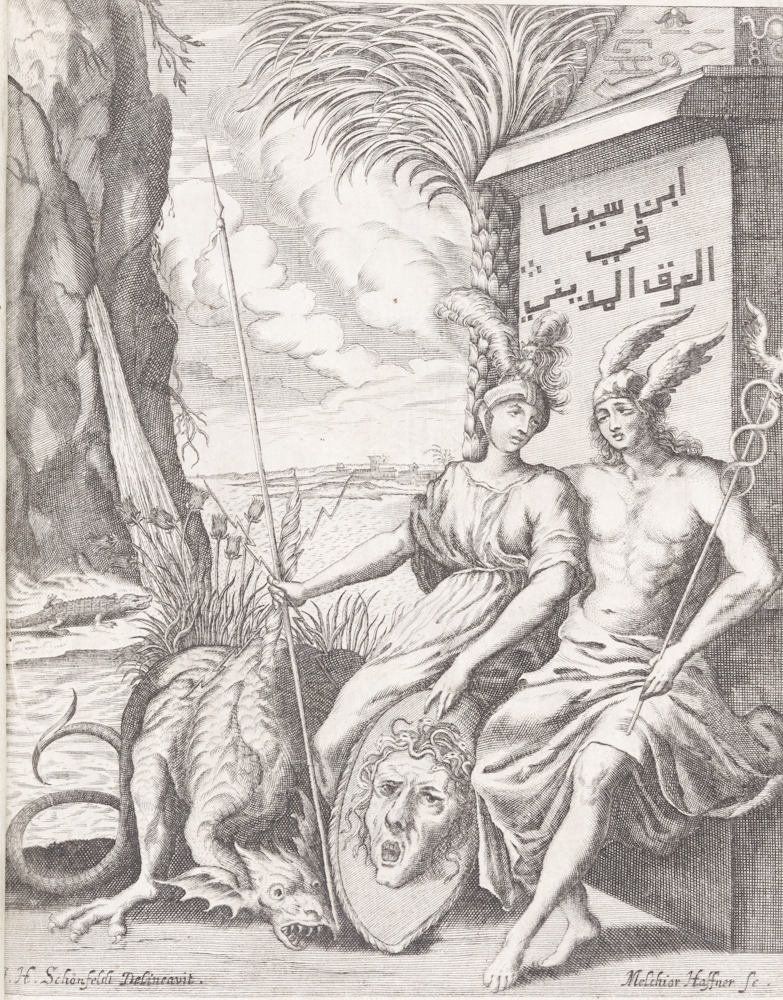

If you hear the word dracunculus in a vacuum, chances are you’ll think of dragons. The frontispiece to the 1674 edition of Georg Hieronymus Welsch’s Exercitatio de Vena Medinensi certainly supports that association. Sitting next to the two Greco-Roman deities Diana and Mercury (identifiable by their shield and staff, respectively) is a dragon, which acts as a visual reference to the work’s full title: Exercitatio de Vena Medinensi, ad mentem Ebnsinae, sive, De Dracunculis Veterum.

This is, however, not the fire breathing serpent of legend. Dracunculus Medinensis (“little dragons from Medina”) is the Latin name of the guinea worm, a parasite that infects humans and causes guinea worm disease. The parasite lives in freshwater, where its larvae are ingested by small crustaceans known as copepods. When mammals ingest these copepods, their casing dissolves in the stomach and releases the larvae, which then mature and mate within the host. While the male D. medinensis die, the females migrate toward the skin’s surface. They then cause a blister on the skin that the worm emerges from over the course of several days or even weeks, a process that is decidedly painful and unpleasant.

But why give the parasite a draconic name? An oft-repeated theory is that they are the “fiery serpents” that God sent to the Israelites as a form of punishment in the Book of Numbers. In the Biblical tale, God tells Moses that the cure for this ailment is to craft a serpent, set it on a pole, and have the people who were afflicted gaze upon it. The symbol of Moses’s brass snake mounted on a pole is known as the nehushtan, and it offersinsight into why people may have thought D. medinensis werethe Biblical serpents.

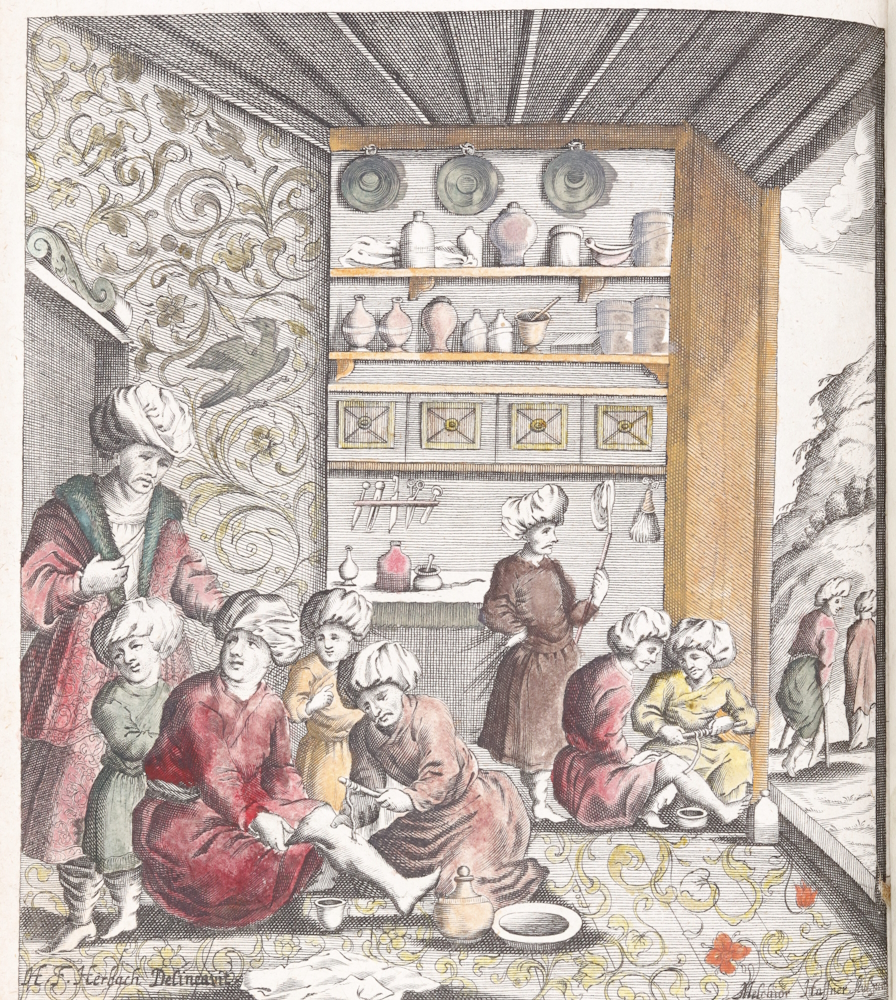

Look at this illustration from Welsch’s monograph.

Welsch’s text is arguably the most comprehensive work on guinea worm disease published during the early modern period. It draws heavily from the writings of the medieval Arabic physician Avicenna, and it includes the original text printed in Arabic in addition to the translated Latin text. Its most striking feature, however, is probably the illustrations. The ones depicting the parasite and its extraction are the most interesting from a clinical perspective. Shown here is the most common method for treating guinea worm disease, which has remained unchanged for centuries and is still practiced today. As the worm emerges from the host’s body, it is wound slowly around a stick. Care must be taken to not break the worm before it has fully emerged, as that could lead to infection, and the entire process can take up to several weeks. When we look at it, it becomes clear that the image of the worm wrapped around the stick is undeniably similar to Moses’s nehushtan.

Other illustrations reveal Welsch’s fascination with the history and iconography of D. medinensis. Several pages show various fossilized worm-like creatures, coins with serpent imagery, and serpentine Roman standards. There are also depictions of Asclepius holding his trademark staff with a serpent wrapped around it. While the Rod of Asclepius also bears a striking resemblance to the nehushtan, this is almost certainly a result of both symbols coming from the same ancient archetype rather than any direct connection.

While the guinea worm disease is a horrible affliction, there is some good news. Preventing infection is manageable through education on how to filter drinking water, and a campaign to eradicate guinea worm began in the 1980s. Over the past several decades, cases have dropped by 99%, and the disease will hopefully be classified as eradicated in 2030. Information on efforts to eradicate guinea worm disease can be found on the WHO’s website.

Welsch’s book will be on display in the Glaser Gallery as part of our upcoming exhibit Adapting Knowledge: How Medicine Evolved Through Global Exchange, along with other works that highlight the medical ideas that connected the early modern world.