What’s a fancy headband doing in an exhibit on historic hearing aids?

This headband, called an Aurolese Phone, is on display along with more than 60 other hearing devices in a new exhibit at Becker Library called “How did we get hear? Historic hearing devices, 1800-2000.” Compared with the conversation tubes, ear trumpets, and more familiar-looking electronic hearing aids on display in Glaser Gallery, this floral headband seems rather out of place.

Also known as the Flower Auricle, this Aurolese Phone was manufactured by F.C. Rein around 1802, and at first glance simply appears to be a decorative headband or hair ornament. At one end of the thin metal headband is a metal flower with fluted petals, painted white. Inside the flower are five delicate, yellow-tipped metal stamens. A hollow green stem extends from the funnel of the petals and curls into a tight spiral.

What makes this hair ornament unique, however, is that the flower stem continues from its spiral and plugs directly into the wearer’s ear. The flower is in fact an ear trumpet in disguise!

The Aurolese Phone’s gorgeous craftsmanship and ingenious design has made it a stand-out favorite with visitors to the exhibit. In this post we’ll take a deeper look at how the Aurolese Phone could have helped you hear and how well it worked.

How could a headband help you hear?

Ear trumpets were one of the main types of hearing devices available before electrical amplification. They used mechanical methods to collect more soundwaves than the ear by itself, and convey the soundwaves more effectively into the ear canal. The earliest trumpets were made from animal horns or shells, but by the nineteenth century, manufacturers produced ear trumpets in all variety of shapes and sizes.

The Aurolese Phone, despite its fanciful design, operated in much the same way as more traditional ear trumpets. The cone-shaped flower worked as a receiver and collected soundwaves over its relatively large surface area. The soundwaves were then conveyed to the ear by the tapering of the flower and the hollow stem. But how much could this device actually help a person who was hard of hearing?

How well did the Aurolese Phone actually work?

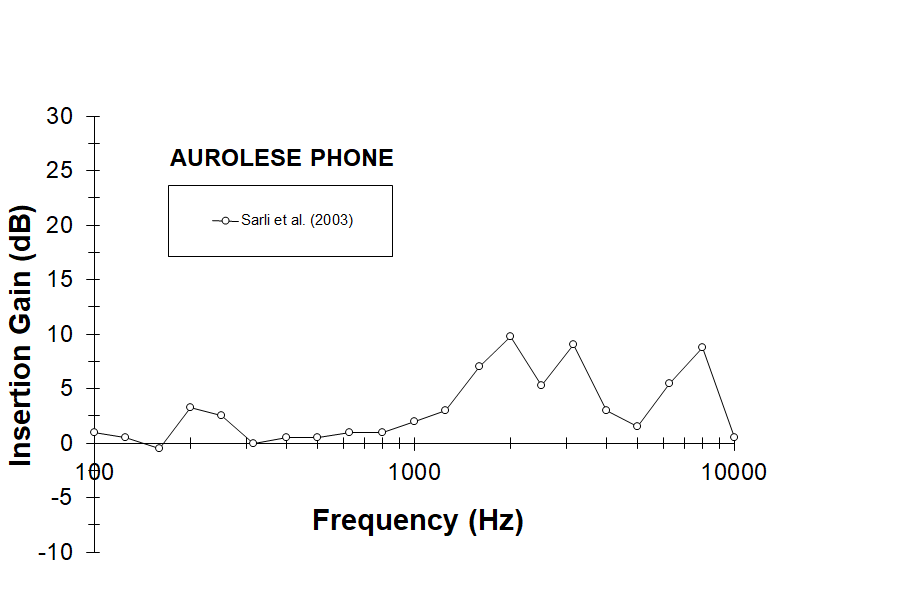

Despite its small size and delicate appearance, the Aurolese Phone may have been helpful for users with mild hearing loss. How do we know? A study done by researchers at the Central Institute for the Deaf (CID) in 2003 actually measured the acoustic benefit of this Aurolese Phone!

The CID researchers measured how much louder (or softer) sounds of different frequencies (or pitches) would be when using the Aurolese Phone, and found that, in general, this device would have provided about the same benefit as you would get from cupping a hand behind your ear.

On average, the Aurolese Phone increased the loudness of sounds by 3.5 decibels in the range of frequencies important for understanding human speech (300 to 3,000 hertz). However, the device did best with sounds in the medium frequency range; the Aurolese Phone increased the loudness of sounds by up to 10 decibels in the frequency range of 1,500 to 2,000 hertz.

It may not seem like a lot, but those extra decibels are certainly nothing to dismiss out of hand — or ear. So, the next time you cup a hand behind your ear to hear something better, imagine you’re slipping on the fashionable and functional Aurolese Phone!

To see the Aurolese Phone in person, along with more than 60 other mechanical and electrical hearing devices, visit our exhibit “How Did We Get Hear? Historic Hearing Devices, 1800-2000.” On view now through February 15, 2023, in the Glaser Gallery in Becker Library.

Sources:

Bernard Becker Medical Library. Deafness in Disguise: Concealed Hearing Devices of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Washington University School of Medicine. Last modified May 14, 2012. beckerexhibits.wustl.edu/did/index.htm.

Carraway, Monique. “Development of a Historic Hearing Devices Exhibit.” Independent study, Washington University in St. Louis, 2001. digitalcommons.wustl.edu/pacs_capstones/279

Koelkebeck, Mary Lou, Colleen Detjen, and Donald R. Calvert. Historic Devices for Hearing: The CID-Goldstein Collection. Saint Louis, MO: Central Institute for the Deaf, 1984.

Sarli, Cathy C., Rosalie M. Uchanski, Arnold Heidbreder, Kimberly Readmond, and Brent Spehar. “19th-Century Camouflaged Mechanical Hearing Devices.” Otology & Neurotology 24, no. 4 (2003): 691-698.