Once a year, Becker Library’s Archives and Rare Books Division brings out the “greatest hits” of the rare book collection for the Annual Display of Rare Anatomical Texts. The display is an opportunity to see these spectacular works up close.

Below is a self-guided tour to help provide a deeper appreciation for select items that will be on display. Printed copies will also be available.

1: Mondino de Luzzi. De omnibus humani corporis interioribus membris anathomia. Impressit Argentine [Strasbourg] : Martinus Flach, anno Domini 1513.

Mondino de Luzzi (c.1270-1326) was an Italian physician who lived and worked in Bologna. When Mondino assumed his teaching position at the university, human dissection had been a neglected aspect of the medical curriculum for nearly a millennium. He reintroduced the practice in roughly 1318, planting the seeds for the anatomical revolution that would flourish in the 16th century.

Mondino published his anatomical observations as the “Anathomia corporis humani,” which first appeared in manuscript form in the 14th century. It quickly became the standard anatomical text for medical students and remained popular for hundreds of years. The edition on display dates from the early 16th century and features a woodcut illustration of the body surrounded by the signs of the zodiac. The anatomy is crude, but the point of the diagram was to illustrate which zodiac signs governed which body parts—critical knowledge for physicians, as the efficacy of medical procedures was believed to vary depending on coordination with astrological signs.

2: Andreas Vesalius. De humani corporis fabrica. Basileae : Ex officina Joannis Oporini, anno salutis reparatae 1543.

The Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) is one of the most famous figures in the history of medicine. As a professor at the University of Padua in Italy, Vesalius emphasized the importance of performing dissection with one’s own hands, rather than relying on the authority of printed texts, as illustrated by the iconography of Fabrica’s woodcut title page. Vesalius is in the center of the scene, dissecting the body of a female cadaver, while a crowd presses forward for a better look. The barber-surgeon, who traditionally performed the physical act of cutting the body open, has been banished to the foot of the table, where he sharpens the knives for Vesalius.

Johannes Oporinus, who printed the Fabrica, was one of the most skilled printers working in Basel, Switzerland. The final product is truly a masterwork of Renaissance printing. The Fabrica contains over 200 woodcut illustrations expertly integrated into the text, and the text itself is printed in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Even the small details, such as the historiated initials that begin each new section of text, are beautiful examples of the printer’s art.

3: Charles Estienne. La dissection des parties du corps humain. Paris: Simon de Colines, 1546.

Charles Estienne (1504-1564) was born into a notable family of French printers. While he also worked in the family business, he is perhaps most well-known as the author of this 16th-century anatomical text – which was actually printed by his father-in-law. The atlas’s impact suffered somewhat from a case of unfortunate timing. Although it was completed prior to Vesalius’s Fabrica (printed in 1543), Estienne ran into a bout of legal trouble when his collaborator, the surgeon Etienne de la Riviére, filed a lawsuit against Estienne regarding authorship over the finished work. By the time the matter was resolved and the atlas was published in 1545, the Fabrica had set the standard for large illustrated anatomical texts.

The most interesting illustrations in Estienne’s atlas are the ones that depict the female anatomy. Most of the images from that sequence are copies of a series of erotic prints called The Loves of the Gods, which depict the gods Venus and Cupid in various titillating poses.

These woodcuts were probably not made for Estienne’s publication but were simply repurposed for an anatomical publication. If you look closely, you can see a break where part of the woodblock was cut away so that the anatomical details could be inserted.

4: Govard Bidloo. Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams. T’Utrecht: By Jacob van Poolsum, Boekverkooper, 1734.

Govard Bidloo (1649-1713) was a Dutch physician who served as the professor of anatomy at The Hague and in Leiden before he accepted a position as the physician to King William III of England. His most famous work is the anatomical atlas “Anatomia humani corporis,” which was first published in 1685 in Latin.

It is known for representing a shift away from the artistic style of the Italian Renaissance. While atlases such as Vesalius’ show the cadavers in lifelike poses reminiscent of Greco-Roman statuary, images in Bidloo’s work convey the gruesome reality of the dissection table.

Bidloo’s artist, the Dutch painter Gerard de Lairesse, depicted small details such as flies resting on the body and the various pins and clamps used to hold the specimens in place.

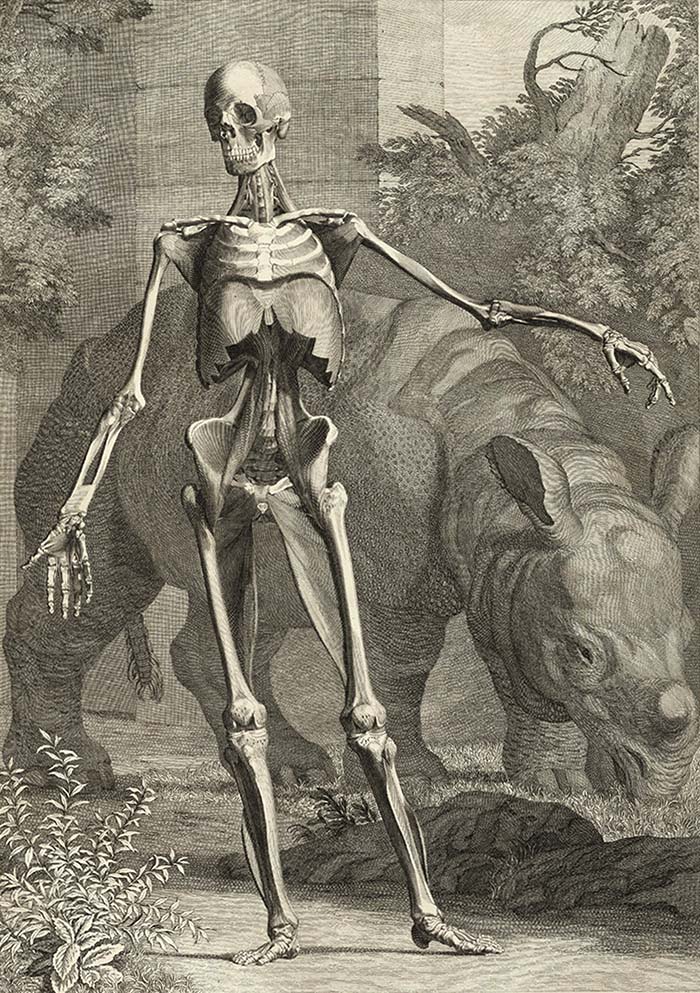

5: Bernhard Siegfried Albinus. Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani. Lugduni Batavorum : Prostant apud Joannem & Hermannum Verbeek, 1747.

Bernhard Albinus (1697-1770) was a German-born Dutch anatomist whose monumental work, “Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani,” demonstrates a wonderful combination of beauty and precision. In order to achieve this level of accuracy and detail, Albinus’ artist, Jan Wandelaar, placed a net with square webbing in front of the anatomical specimens at defined intervals. He then carefully copied the details that were contained within each individual square.

Bernhard Albinus (1697-1770) was a German-born Dutch anatomist whose monumental work, “Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani,” demonstrates a wonderful combination of beauty and precision. In order to achieve this level of accuracy and detail, Albinus’ artist, Jan Wandelaar, placed a net with square webbing in front of the anatomical specimens at defined intervals. He then carefully copied the details that were contained within each individual square.

The most striking images in this atlas are the ones depicting a giant rhinoceros posing alongside the human figure. While the juxtaposition between the graceful human form and the ponderous rhino is certainly impressive, this was not merely an artistic convention. The rhino was actually a real historical figure named Clara! After her mother was killed by hunters, baby Clara was acquired by Jan Albert Sicheterman, director of the Dutch East Indian Company in Bengal. He later sold her to a colleague, who brought her back to the Netherlands and promptly took her on a grand tour of Europe. As she was the first live rhino that Europeans had seen in centuries, she caused a sensation, and images of Clara appear in numerous prints and sculptures produced during the 18th century. She died in 1758 at age 20.

6: Antonio Scarpa. Tabulae nevrologicae. Ticini [Pavia] : Apud Balthassarem Comini, 1794.

Antonio Scarpa (1752-1832) was one of the many Italian physicians who studied at the University of Padua. He traveled widely throughout Europe after earning his medical degree and was appointed Professor of Anatomy at the University of Pavia at the behest of Austrian Emperor Joseph II.

His most famous work is his immense neurological atlas displayed here. It represented the culmination of twenty years of anatomical research and included the first proper depiction of the vagus and cardiac nerves. It also demonstrated Scarpa’s artistic ability. Scarpa himself drew many of the illustrations, while others were created with the assistance of Faustino Anderlino, whom Scarpa personally trained.

Visitors can still see Scarpa’s preserved head at the Museo per la Storia dell’Universitá di Pavia.

7: Claude Perrault. Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire naturelle des animaux. A Paris: De l’Imprimerie royale, 1676.

Claude Perrault (1613-1688) was a French architect and natural historian. In 1666, he was invited to become a founding member of the French Academy of Sciences, a learned society established by King Louis XIV to promote the spirit of scientific research in France. As a member of the academy, Perrault oversaw a team of anatomists dissecting various animals that died in the royal menagerie, including a thresher shark, a lion, a beaver and a cassowary.

The results of their research were collected in the Mémoires. The 1676 edition (displayed here) contains descriptions of 29 species, accompanied by beautiful full-page copperplate engravings. Many of these were done by Sébastien Leclerc, engraver to Louis XIV, and were created at great expense – more than 4,000 livres. The illustrations contain not only the dissected anatomical parts, but the living animals shown in various natural landscapes.

Given the size of the volume and the expense that went into its production, this was meant as a presentation volume to be given to various high-ranking persons as an expression of royal favor. This was confirmed by Alexander Pitfield in 1688, who noted when he was working on his English translation that few copies of the original volumes were available, as they had been given away to “persons of the greatest quality.”

8: Florence Fenwick Miller. An Atlas of Anatomy. London: Edward Stanford, 1879.

Florence Fenwick Miller (1854-1935) was an English journalist and social reformer. In 1871, she read for a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh, but since the university had decided not to award medical degrees to women, she did not actually receive the MD designation. She instead earned a midwifery certificate from the Ladies’ Medical College in London.

While Miller practiced obstetrics for a while in London, she quickly became known for her activities as a woman’s rights activist. In her career as a journalist, she wrote the “Ladies’ Notes” column for the Illustrated London News, and between 1895 and 1899, she served as the editor and owner of the Woman’s Signal, a British feminist periodical. In 1893, she traveled to the World’s Fair in Chicago as a delegate to the World’s Congress of Representative Women, and in 1902, she became a founding member of the International Council of Women.

Her medical roots come through most clearly in her publications. She wrote a number of books on anatomy and physiology, including the one displayed here. These were intended for a lay audience, meant to provide information for those who were interested in the medicine but had no formal training.

9: John Lizars. A system of anatomical plates of the human body. Edinburgh : Published by W.H. Lizars, S. Highley, London, and W. Curry Junr. & Co. Dublin, [1840].

John Lizars (c.1791-1860) was a Scottish surgeon born into a publishing family. His father, Daniel Lizars, was a printer and engraver working in Edinburgh, and his brother, William Home Lizars, was a well-regarded painter whose works were displayed at the Royal Academy in London before he went into business as an engraver. The firm produced various engravings including landscapes, maps and Scottish scenes.

Lizars attended Edinburgh University and learned surgery and anatomy from the notable Scottish surgeon John Bell. He spent a few years serving in the military, then returned to Edinburgh, where he was elected to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and became the senior operating surgeon at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. He was the first British surgeon to perform an ovariectomy.

“System of Anatomical Plates of the Human Body” is his most famous work. The beautifully engraved plates were created by his brother William, and the volumes were published by the family firm.

10: Eduard Pernkopf. Atlas of topographical and applied human anatomy. Philadelphia : W. B. Saunders Co., 1963-64.

The anatomical atlas of the Austrian anatomist Eduard Pernkopf (1888-1955) occupies an extremely controversial position in the history of medicine. Pernkopf was a professor of anatomy at the University of Vienna during the Third Reich, and a fervent supporter of Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist regime. He began working on his anatomical atlas in 1933 with the assistance of four artists: Erich Leiper, Ludwig Schrott, Karl Endtresser and Franz Batke. All were members of the Nazi party, who sometimes incorporated the Nazi swastika and SS lightning bolt into their signatures, which have been airbrushed out of editions printed after the 1960s.

There is considerable controversy regarding the origin of the cadavers used by Pernkopf’s team. During the period when he was carrying out his dissections, the bodies of nearly 1,400 executed persons were delivered to the university’s medical department. It is a distinct possibility that some became the basis of the images in Pernkopf’s atlas.

The question of how to approach this work is fraught with difficulty. The illustrations themselves are superb; however, the creators were willing supporters of a genocidal regime and almost certainly utilized the victims of that regime in their work. We choose to display this atlas out of an understanding that the history of medicine is not a straightforward march of forward progress.

Many people over the centuries have had their bodily autonomy stripped from them in the service of anatomical knowledge. We believe it is important for those in the medical profession to be aware of these unsavory aspects of medicine’s legacy in order to make ethical decisions in the future.