One of the joys of reading primary sources is that it can provide us with a direct window into the past—browsing through an old distillation manual can lead down the path of researching medicinal cannibalism, or mentions of moon phases can provoke a segue into medical astrology. But it isn’t just the words that can open windows onto the past; the manner in which they are written also gives us valuable knowledge about how the art of presenting knowledge has evolved over time.

Modern monographs tend to be very straightforward, especially works whose aim is to be informative and educational—like a textbook—rather than entertaining or experimental, such as novels or poetry. We expect their information to be told in narrative format, in neatly laid out paragraphs, with the author held at something of a distance. One thing we probably wouldn’t expect to find—except perhaps in plays—is characters debating each other. For example, a contemporary academic monograph on pathology would not feature Giovanni Morgagni and Rudolf Virchow sitting together in a sunlit garden discussing various pathological anomalies.

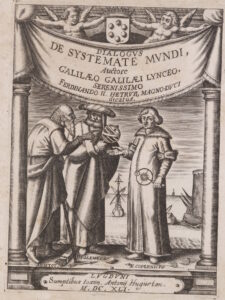

But this was not always the case. The dialogue format was once frequently used in a wide variety of texts, including works on theology, medicine, and science. One of the most famous examples of a scientific dialogue is Galileo Galilei’s Dialogus de systemate mundi, in which the characters Salviati, Sagredo, and Simplicio debate the question of whether or not the earth moves. Salviati (usually seen as a stand-in for Galileo himself) is in favor of the Copernican position—that the earth moves—while Simplicio is an adherent of the older Aristotelian-Ptolemaic system, in which it remains still. Sagredo is not committed to either school, but is willing to be persuaded by whoever has the soundest arguments.

Galileo’s dialogue is a fine example of what we might call a Socratic dialogue. These dialogues take their name from Socrates, arguably the most famous of the Greek philosophers, although it was Socrates’s student Plato who first put them in writing. Socratic dialogues focus on critical thinking, using a series of questions and answers to probe at the logic underlying the subject under discussion. By doing so, any underlying contradictions and fallacies will be brought to the surface. This “Socratic Method” is still used today in many educational settings. For example, the Law School at the University of Chicago views the Socratic Method as a cornerstone of its teaching philosophy, using it to “develop critical thinking skills in students and enable them to approach the law as intellectuals.”

Not all academic dialogues were aimed to show an argument’s underlying weaknesses and contradictions. Some of them were very straightforward and were essentially informational treatises with the dialogue serving as an artistic flourish. Take, for instance, Justine Siegemund’s Hof-Wehe-Mütter, a treatise on midwifery first published in 1690. When we turn to the first chapter, we find ourselves witnessing a dialogue between two “peaceable midwives” (Friedliebenden Wehe-Mütter), Justina and Christina. Justina is, of course, the author herself; Christina is a younger midwife with less experience. Christina often addresses Justina as her “beloved sister” and the questions are meant to highlight some aspect of birth. For example, Justina asks what is to be done when the water breaks a few days before the birth; Christina responds that if all else is well, there is nothing to do but wait.

So, why exactly was the dialogue format so popular during this time? The most obvious reason is the rise of Renaissance humanism, a movement that emphasized the rediscovery of Greek and Roman texts—which included dialogues. But a desire to pay homage to classical heroes was not the only reason early modern authors embraced the dialogue. As historian Peter Burke points out, when printing appeared in Europe in the mid-1400s, the intellectual culture was still very much an oral one. Universities emphasized the importance of debate as a means of learning, and rhetoric—the art of persuasion—was an important skill for scholars to have. This emphasis on eloquence and erudition continued into the early modern period, and guides on how to be an effective orator could often be found in scholarly libraries.

Dialogues could also be a clever way of eluding censorship in a time when publishing was closely monitored. Because the characters in dialogues were often either allegorical figures or famous people from history and literature, authors could claim that any controversial views espoused in the dialogue were not theirs—they were, after all, words in the mouths of literary characters. Perhaps this is a strategy that could use reexamination!

While the academic dialogue has faded from favor over the centuries, it serves as a reminder that the presentation of knowledge provides insight into the culture that created it. Our modern society puts less emphasis on skilled oration than that of medieval and early modern Europe, so it stands to reason that we’ve moved away from the dialogue format. Which might be too bad—just imagine how fascinating it would be to read that conversation between Morgagni and Virchow.

Sources

Printed Voices: The Renaissance Culture of Dialogue. Edited by Dorothea Heitsch and Jean-François Vallée. University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Peter Burke, “The Renaissance Dialogue,” in Renaissance Studies. 3:1 (March 1989) 1-12.