From Feb. 6-10, libraries, archives and other cultural institutions around the world are sharing free coloring sheets and books based on materials from their collections. On the first floor of Becker Library, you’ll find snacks, coloring books and materials, so let your inner child take over! Then show off your masterpiece(s) to the circulation desk to win a special prize.

Want to know more about the images chosen from Becker’s rare books collection? Be sure to read on!

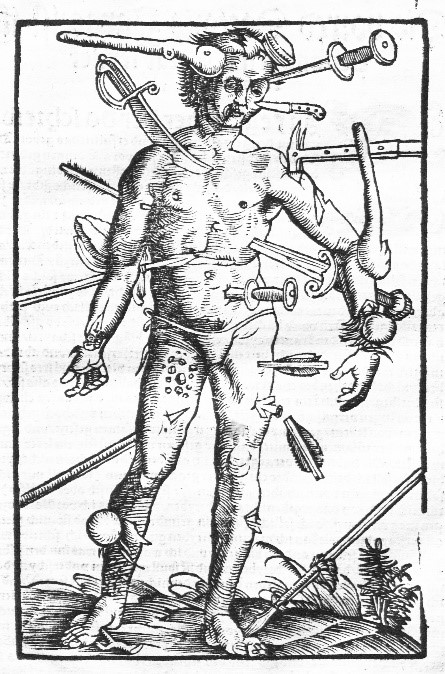

Paracelsus. “Der grossenn Wundartzney, das erst Bůch.” 1537.

Fans of Thomas Harris’s “Red Dragon” or NBC’s “Hannibal” may find this image familiar. A “Wound Man” is a surgical learning aid that depicts various injuries, such as from war, accidents, and disease. They first appeared in European medical manuscripts in the 145th-15th centuries and were printed in books through the 17th century.

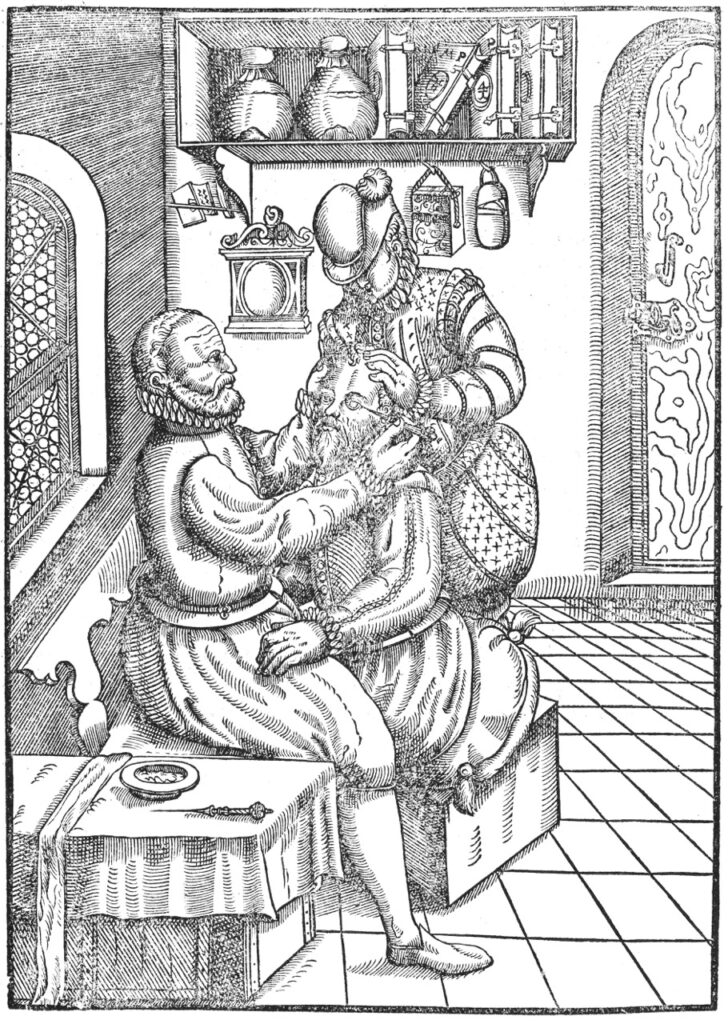

George Bartisch. “Ophthalmodouleia, das ist, Augendienst.” 1583.

Bartisch (1535-1607) was a German physician and is considered the father of ophthalmology. His work, “Ophthalmodouleia,” was published in 1583 and covers topics such as external eye diseases and trauma, strabismus, and eye anatomy. Also discussed are his theories on diagnosing and treating cataracts by color. The work allows the reader to explore the anatomy of the brain and eyes through the use of flap illustrations, which depicted the different layers of these organs and body parts.

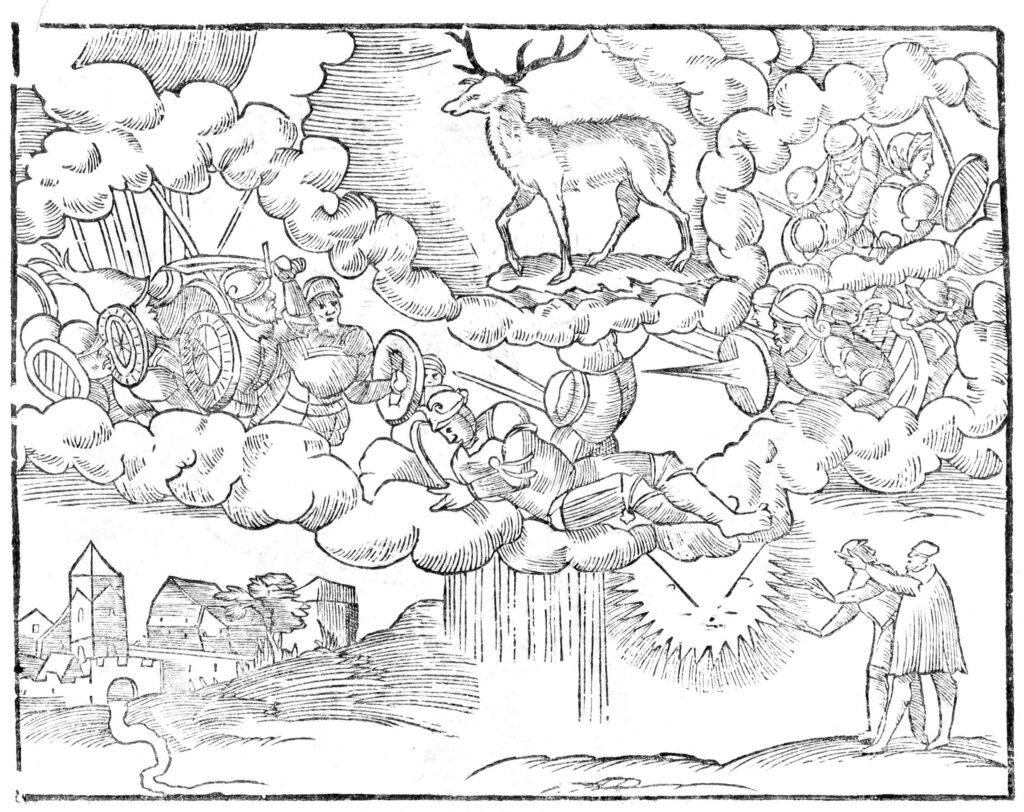

Ulisse Aldrovandi. “Monstrorum historia.” 1642.

“Monstrorum Historia” is a visually stunning book on “monsters” and fantastical races, such as centaurs, cyclops, satyrs, and mermen, The work is part of a larger 13-volume encyclopedia on natural history, reflecting Aldrovandi’s interest in collecting specimens of plants, animals, minerals and fossils. In addition to the fantastical races and “monsters” that we would now understand as symptoms of disease or genetic conditions, there are also reports on dragons and other miraculous events that would have been considered natural phenomena.

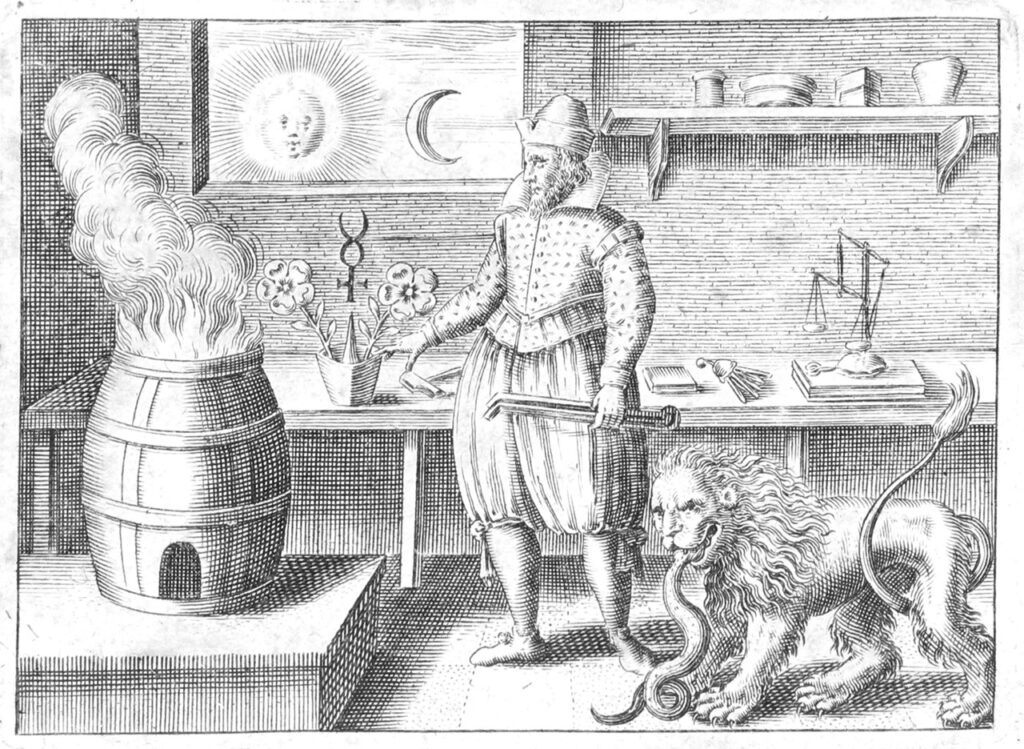

Johann Daniel Mylius. “Opus medico-chymicum, 1618-1630.“

Johann Daniel Mylius (c.1583-1642) studied theology and medicine at the University of Marburg and was a student when he wrote this book. This work is one of the many rare books on alchemy in Becker’s collections. Some people, such as the physicians who followed the Paracelsian school of thought, believed alchemy was the basis of a reformed medicine (as opposed to fields such as mathematics).

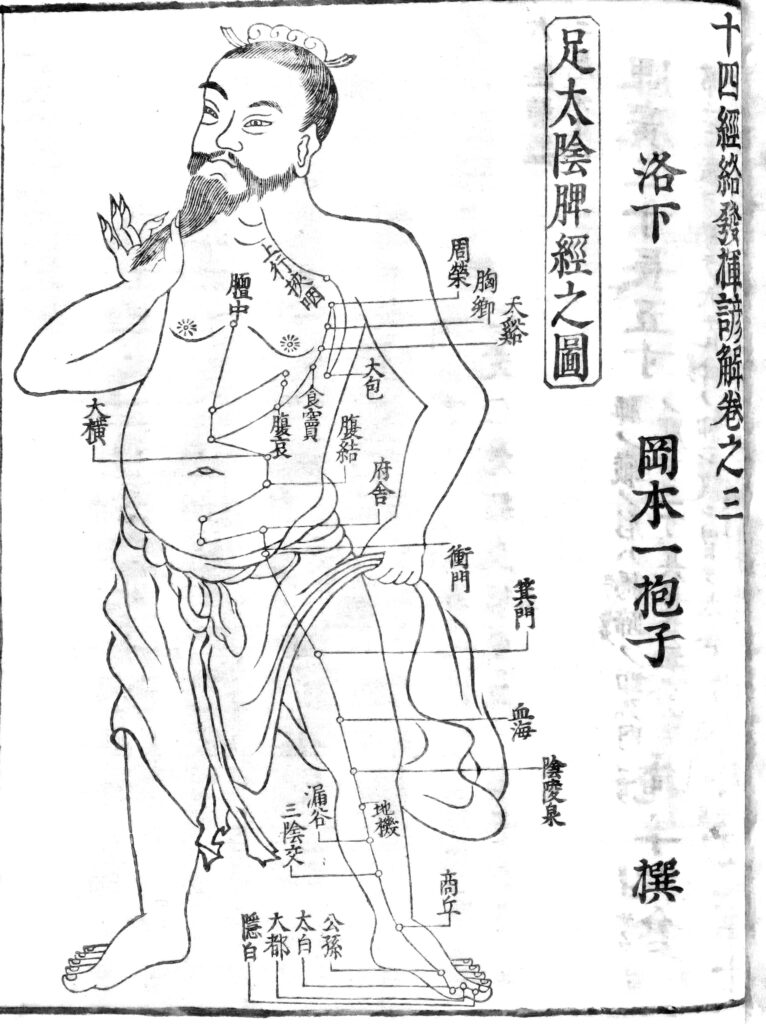

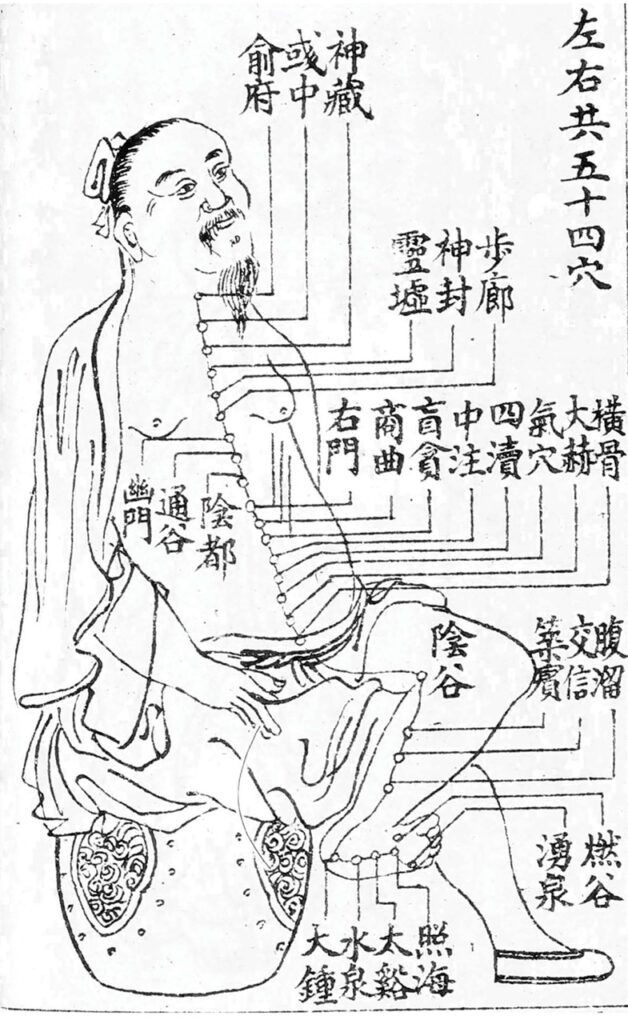

Shou Hua. “Jushi keiraku hakku wage (Commentary on Shi si jing fa in Japanese).” Translated by Ippo Okamoto. 1693.

Intellectual links between Japanese and Chinese medicine have been strong throughout both countries’ histories, as shown by this Japanese edition of Shou Hua’s “Shi si jing fa hui (Elucidation of the 14 acu-tracts).” First published in 1341 in China, it deals with the practice of acupuncture, one of Hua’s areas of interest. In Chinese medicine, Hua is known for expanding the number of acupuncture meridians from twelve to fourteen, and for his work on medical theories related to moxibustion, a medical practice in which dried mugwort is burned on top of the body.

This edition of Hua’s work was translated and edited by Ippo Okamoto, a 17th-century Japanese physician. Its woodcut illustrations depict the centers for acupuncture, while the text focuses on the eight vital blood vessels and the circulation of life through the fourteen meridians.

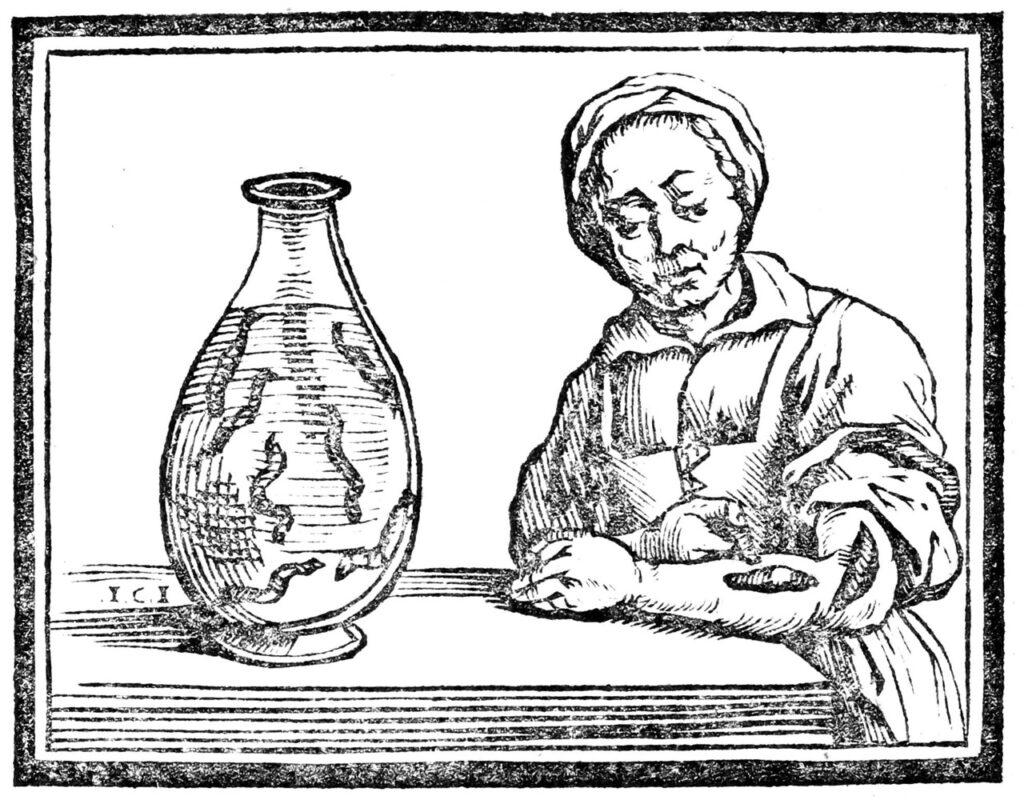

Guillaume van den Bossche. “Historia medica.” 1639.

During the Middle Ages it was believed that one’s health was influenced by the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile) in one’s body. Leeches were used as a means of balancing these humors, as they could reduce what was seen as an excess of blood. They were seen as a method of bloodletting, which itself was a common practice, and as a result leeches became so popular as a means of treatment that during the 19th century, France imported 40 million leeches for medical purposes.

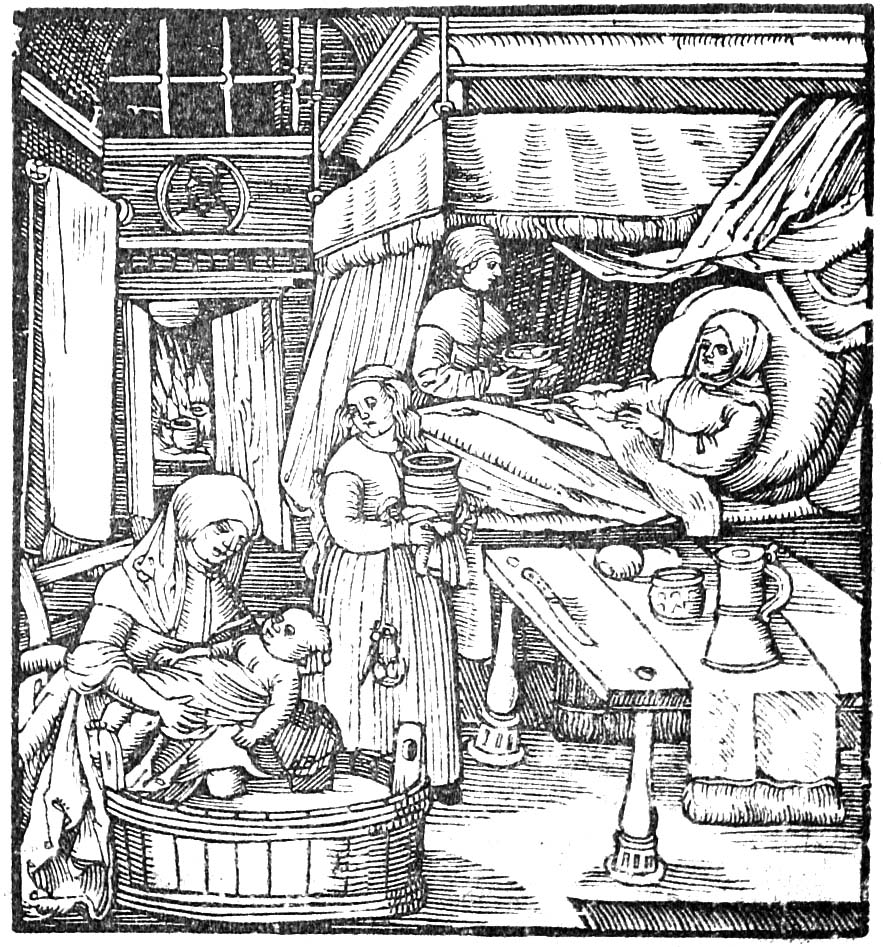

Eucharius Rösslin. “Eucharius Rösslin’s ‘Rosengarten’”. 1910.

Eucharius Rösslin (c.1470-1526) was a German physician in the city of Worms under the service of Catherine of Pomerania-Wolgast. Rösslin saw the city’s midwifery practices to be substandard and contributing to the high rates of infant mortality; he wrote “Der Rosengarten (The Rose Garden)” in response (published in 1513), which became a standard text for midwives. The work is in vernacular German to make it more accessible, and features some of the first illustrations depicting the fetus in utero, the birthing chair, and the lying-in chamber.

Cutter (1807-1872) was an American physician who toured and gave medical lectures. This background inspired him to publish works, such as this treatise, as textbooks for schools and colleges. Cutter also later became an active abolitionist and later joined the military. He served the army as a surgeon during the Civil War and was captured as a prisoner during the Battle of Bull Run.

Zhang Jiebin. “Jing Xiao Zhangshi Lei Jing.” [c. 1912-1949].

The “Huangdi Neijing,” or the Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic, is an ancient Chinese medical text (or group of medical texts) that has been considered the foundation of Chinese medicine. The work is broken up into two parts—the Suwen (素問) or Basic Questions, which covers the theoretical foundation of Chinese medicine and its diagnostic methods; and the Lingshu (靈樞) which covers acupuncture. In addition to Chinese medicine, the work is considered an important text on Daoist theories and lifestyle, discussing how forces such as yin and yang, qi, and the wuxing (the five elements or phases) impacted the universe; and in a parallel fashion how these also could impact the human body— that diseases were the effects that resulted from one’s environment, diet, age, and emotions. Thus, although it discusses the human body and acupuncture, it is in a very different sense than more modern anatomical texts.

Chinese medical texts were hermeneutical in nature, which mean that there was a scholarly tradition of building on and reinterpreting older works. The Leijing, published in 1624 by Zhang Jiebin, was based off the Suwen of the Neijing. Presented here is a copy of Jing Xiao Zhangshi Leijing (Explaining Master Zhang’s Leijing), which in turn builds on and reinterprets Zhang’s Leijing; annotated notes are denoted by smaller characters compared to the rest of the inline text. There are sixteen volumes, of which the first ten include contents covering topics such as diagnoses of the organs and meridians, pathology, and treatment of diseases. The remaining six volumes are an appendix of the illustrations in the work.

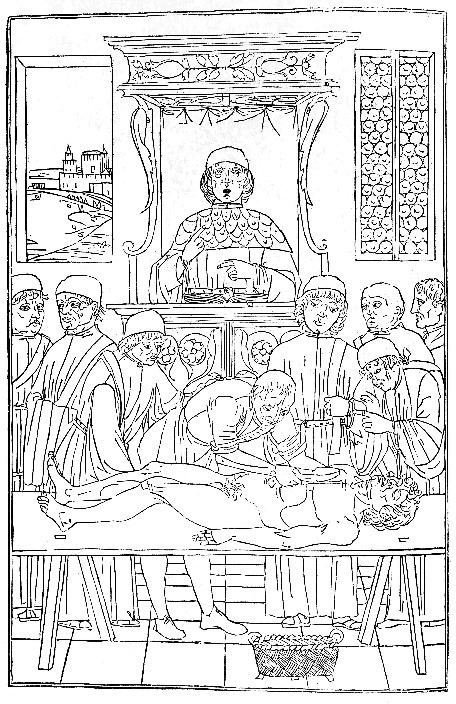

Joannes de Ketham. “The Fasciculus Medicinae.” 1491.

“Fasciculus Medicinae” was a group of six medical treatises and illustrations that were printed together, and feature the first illustrated practical treatise on medicine issued from the European printing press. Images include engravings depicting dissection, a Wound Man, a Zodiac Man, and a urine chart. Although Joannes de Ketham’s name is often associated with the work, he had nothing to do with its creation – he was merely an owner of one copy of the manuscripts.

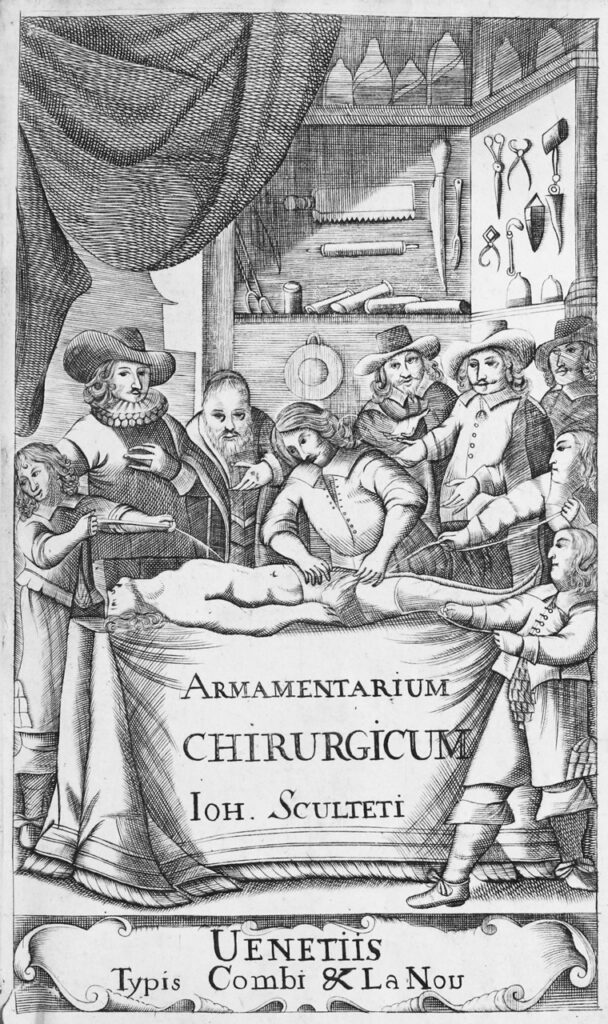

Johannes Scultetus. “Armamentarium chirurgicum.” 1656.

Scultetus (1595-1645) was a revolutionary 17th-century work on surgical instruments and procedures. Scultetus pushed for formal education for barber-surgeons in his hometown of Ulm. The work covers procedures such as cesarean sections, arterial litigations and mastectomy.

Check out #ColorOurCollections on social media for inspiration from other participating institutions, or visit library.nyam.org/colorourcollections/.