In 2015, the Heinz Nixdorf Museum in Paderborn, Germany, opened an exhibition honoring women in computing. In addition to pioneers like Ada Lovelace, the museum recognized the contributions of Mary Allen Wilkes, whose work at MIT and Washington University was essential to the development of the Laboratory Instrument Computer (LINC) then on display at the museum. Dr. Jerry Cox, Jr., a colleague of Wilkes’ at Washington University, attended the opening and recalled, “Mary Allen gave a short speech in German. What a tour de force!”1

Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1937, Wilkes attended Wellesley College with aspirations to become a lawyer. But when she graduated in 1959 with a degree in philosophy, she had been discouraged from pursuing a legal career, advised that the path to practicing law would be difficult, if not impossible, as a woman. And so, after graduation, she made her way to the MIT employment office to inquire about computer programming jobs. She was hired on the spot.2

When she began working at MIT, Wilkes had no experience in programming. This was not unusual at the time; programmable computers as we understand them today were in their infancy. The first electronic, digital, programmable computer, the ENIAC, had only just been introduced in 1946. Previously, “computers” referred not to machines, but to humans, who performed complex calculations manually. Many computers were women with advanced training in mathematics.

Wilkes’ new employer saw her philosophy degree as a plus. In addition to a background in symbolic logic, she had, in her own words, “a very picky, precise mind”–an ideal trait for tasks requiring attention to detail, like translating lines of code from one’s head onto paper.3

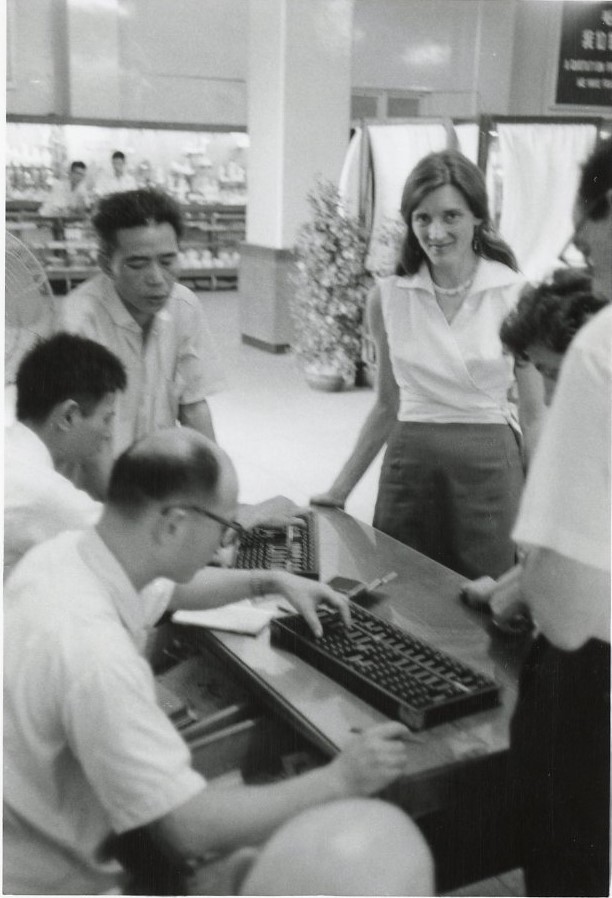

In 1961, Wilkes joined Wesley Clark’s team at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, which had begun to tackle a dilemma for biomedical researchers interested in using computers for their work. Existing machines could not process data during an experiment, limiting the ability of researchers to make adjustments in real time. And the large, time-sharing computers common at the time were too cumbersome for laboratory use, which needed more nimble machines. Their solution was the LINC. Today considered one of the first personal computers, the LINC was interactive, mobile, and small for its time. It had its own keyboard and display screen, along with an innovative tape unit that could store data and programs.

While Wesley Clark and Charles Molnar developed the LINC hardware, it was Mary Allen Wilkes who developed its software. Their work continued in Massachusetts until 1964, when the LINC team moved from MIT to Washington University in St. Louis. Wilkes, not ready to relocate, finished writing the operating system on a LINC installed in her parents’ living room in Baltimore. In addition to making programming as much as 100 times faster, the LINC Assembly Program (LAP) gave users an unprecedented amount control over their experiments. The user-friendly LAP and its subsequent versions, culminating in LAP6, enabled non-computer professionals to modify the program to meet their research needs, as Wilkes described in a 1970 journal article.

Today, software development is regarded as prestigious and profitable. This was not always the case. Early in the computer age, programming was considered clerical work, deliberately portrayed as a “feminine skill.” After all, the thinking went, women could be paid less than men.4 As more women joined the profession during World War II, the labor they performed was simultaneously extoled as essential and diminished as “subprofessional,” their contributions undervalued and unrecognized.5 When the term “software engineering” was introduced in the late 1960s, it linked the work of programming to a male-dominated discipline with greater professional and academic standing. This, too, had gendered consequences: “programmers were accorded a lower status than engineers—and…programming was seen as less skilled because women did it.”6

When Wilkes became a programmer in the early 1960s, women held 27% of occupations classified as computer and mathematical. The number of women working in such jobs peaked at 35% in 1990, but by 2013, it had dropped to 26%, where it has held steady for the past decade. The number of women pursuing computer science degrees has followed a similar pattern. Women comprised 15% of graduates with a bachelor’s degree in computer science in 1966. The percentage rose to 37% in 1984, but ten years later, it had dwindled to 28.4%. By 2012, it had plummeted to 17.7%. Women’s share of computer science bachelor’s degrees increased to 20.9% in 2022, but remains below its mid-1980s peak. Black women in particular continue to be underrepresented, their share hovering around 2.5% during the past decade.

Women’s underrepresentation in computer science has been attributed to both lack of aptitude and lack of interest. Explanations that invoke gender differences in aptitude—“boys are good at science” or “girls are bad at math”—have been widely discredited, but their cultural influence lingers. Interest is more challenging to parse, as lower employment and graduation figures are not necessarily indicative of disinterest. Research suggests factors such as unwelcoming classroom and work environments; a lack of women peers and professional networks; the persistence of stereotypes about tech bros and male nerds; and the actual or perceived lack of desirable career paths, may all play a role.7 When universities have worked to better understand and address the gender imbalance in computer science, some have seen a sustained increase in women’s participation.

Mary Allen Wilkes eventually left the field of computers to pursue her dream of a career in law. She enrolled at Harvard Law School in 1972 and worked as a lawyer and a judge over the next four decades. Hear more from Wilkes in her own words about the LINC and women in computing in this 2019 talk at her alma mater.

- Jerome R. Cox, Jr., Work Hard, Be Kind: A Memoir. St. Louis, MO: Pesca Publishing, 2022, 229. ↩︎

- Clive Thompson, “The Secret History of Women in Coding,” New York Times Magazine, February 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/13/magazine/women-coding-computer-programming.html. ↩︎

- Thompson, “The Secret History of Women in Coding,” 2019. ↩︎

- Janet Abate, Recoding Gender: Women’s Changing Participation in Computing, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012, 64-66. ↩︎

- Jennifer S. Light, “When Computers Were Women,” Technology and Culture 40, no. 3 (1999): 456. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25147356. ↩︎

- Abate, Recoding Gender, 103. ↩︎

- Abate, Recoding Gender, 146-147. ↩︎