Although we are a medical library, not every single volume in our rare book collections takes medicine as its focus. Our shelves also have 19th century novels, 18th century poetry, and 19th century poetry of questionable quality. We also have quite a few travelogues! Today we’ll look at Mungo Park’s account of his explorations in West Africa in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

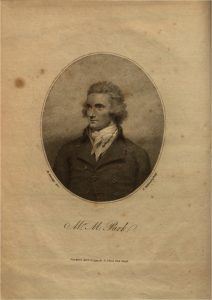

Mungo Park was born near Selkirk, Scotland in 1771, and began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1789. His brother-in-law James Dickson introduced him to Sir Joseph Banks, the President of the Royal Society, in 1792. This proved fortuitous for Park. Through Banks, Park received a year-long position as an assistant surgeon for the East India Company in Sumatra, and it was at Banks’ recommendation that Park set out to explore the African interior in in 1795 on the behalf of the African Association.[1]

Mungo Park was born near Selkirk, Scotland in 1771, and began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1789. His brother-in-law James Dickson introduced him to Sir Joseph Banks, the President of the Royal Society, in 1792. This proved fortuitous for Park. Through Banks, Park received a year-long position as an assistant surgeon for the East India Company in Sumatra, and it was at Banks’ recommendation that Park set out to explore the African interior in in 1795 on the behalf of the African Association.[1]

Founded by Banks in 1788, the African Association was one of several Enlightenment-era organizations with a broad interest in science and exploration. Its aim was to investigate the parts of the globe that had been mysterious up to that point; they decided to focus on Africa in particular because while inroads were being made in America and Asia, the African continent remained mostly unexplored. One matter that the Association was particularly interested in was the course of the Niger River. The Niger is unusual in that it flows in a wide curve across western Africa, rather than in a (relatively) straight line, and this had stymied European geographers for quite some time. The questions of whether it flowed west-east, shared a common source with the Nile, or met the Nile’s headwaters remained unresolved. One of the aims of Park’s expedition was to resolve these questions.[2]

Park set out for West Africa in May 1795, and landed in the Gambia in June. He reached the Niger River on July 21st at Ségou in Mali, and described the moment in ecstatic terms:

I saw with infinite pleasure the great object of my mission; the long, sought for, majestic Niger, glittering to the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at Westminster, and flowing slowly to the eastward. I hastened to the brink, and, having drank of the water, lifting up my fervent thanks in prayer, to the Great Ruler of all things, for having thus far crowned my endeavours with success.[3]

On this initial trip, Park did not journey the entire length of the Niger. Illness kept him in the village of Kamalia for seven months, and he arrived back in the Gambia in June 1797. He returned to London via the West Indies in December 1797.

Park failed to locate the Niger delta on his initial journey. He embarked on a second journey in April 1805, this time accompanied by a military company from the Royal African Corps. It would have a tragic outcome. When the party reached the rapids at Bussa in modern Nigeria, it was attacked by natives and all but one man drowned. Park’s body was never recovered.

Park is often credited with popularizing African travel literature, and for providing the British with a sympathetic portrait of the people of Africa. His Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa was published in 1799 and contains observations on the various cultures he encountered, pictures of plants and village life, and maps. The journal of his second journey, documenting his travels up until Sansanding in Mali, was published posthumously in 1815. He had given the journal to his servant, Isaaco, to send back to England, and it was not with him when he perished.

[1] "Park, Mungo." In Dictionary of African Biography. : Oxford University Press, 2012. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195382075.001.0001/acref-9780195382075-e-1663

[2] A. Adu Boahen, “The African Association, 1788-1805,” Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana Vol. 5, No.1 (1961): 43-64.

[3] Mungo Park, Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa, London: W. Bulmer and Company, 1799: 194-195.