Part 1 covers a few of the people associated with Washington University who played a part in the building of the atomic bomb with reference to the 2023 film Oppenheimer.

Part 2 focuses on the part Arthur Holly Compton played in Robert J. Oppenheimer’s life and as inspiration for the movie. There are spoilers for the ending of Oppenheimer in Part 2.

In his Academy Award winning 2023 film Oppenheimer filmmaker Christopher Nolan deftly shapes the vast story of the building of the atomic bomb and the tension and fears at the birth of the atomic age into a morality tale centered on the figure of American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The movie hinges around an actual event in the history of the atomic bomb. Early in the bomb’s development initial calculations showed there was a chance that if an atomic bomb were detonated the cascading nuclear reaction would set fire to the entire Earth’s atmosphere. In the movie, Oppenheimer rushes to a secret meeting with eminent physicist, Albert Einstein.

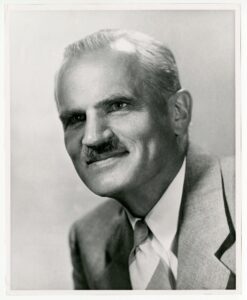

In reality, Oppenheimer went to see the person who had hired him and who was ultimately responsible for the construction of the bomb, Arthur Holly Compton. The film’s director, Christopher Nolan told The New York Times he made this change to have more of an impact on the audience because “Einstein is the personality people know.”3 Though Compton is not a household name like Einstein, by the 1940s Compton was one of the most well-known and well-regarded physicists.

Richard Rhodes, author of the book The Making of the Atomic Bomb, says that Compton, “was in a sense the scientific leader of the Manhattan Project. People confuse that with Oppenheimer, because Oppenheimer was so charismatic and well-known after the war.”4

Compton’s association with Washington University began in 1920, when he became Professor and head of the Department of Physics. Working in his lab in the basement of Eads Hall he experimented with bombarding graphite with x-rays and discovered an “x-ray scattering effect” which is now known as the “Compton effect.” He published his observations and his comprehensive mathematical explanation in 1923. In 1927, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics. The amazingly short time between his experiments and winning the Nobel shows the importance of his discovery. Compton demonstrated that x-rays, imagined to be waves, could also behave as particles. His research was a cornerstone in the understanding how electromagnetic radiation interacts with atoms and the development of quantum theory.6

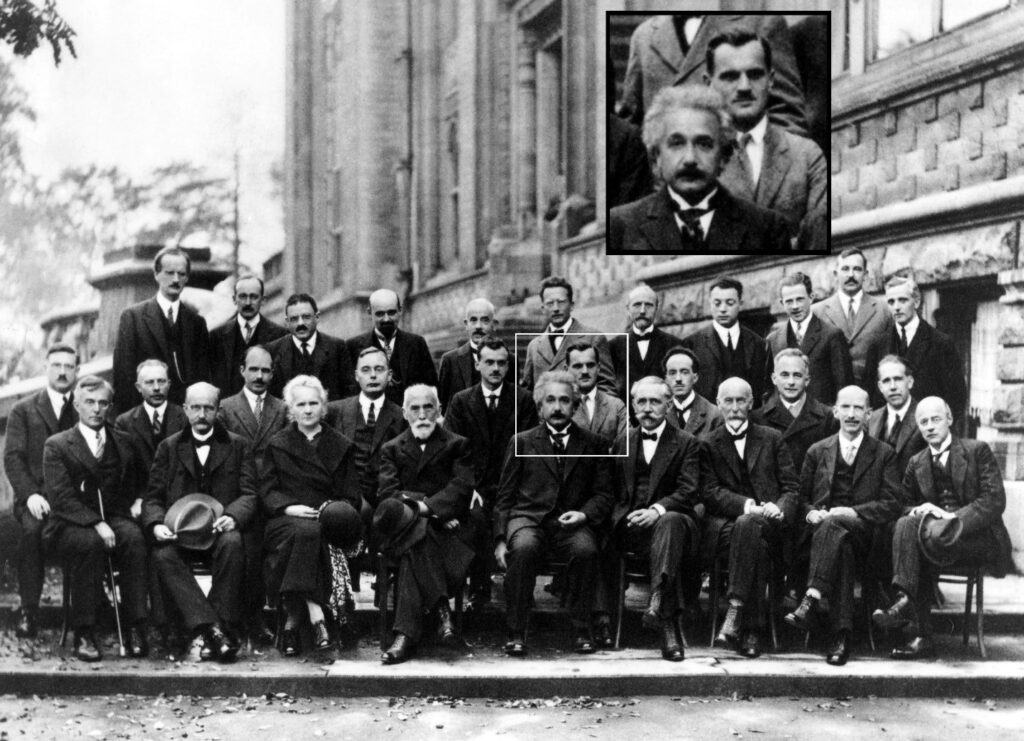

Just before he won the Nobel Prize, Compton was invited to the 1927 Solvay Conference on Physics where the world’s most notable physicists met to discuss the newly formulated quantum theory.7

While Compton bombarded graphite with x-rays, other researchers investigated similar effects of other types of radiation on other materials. By 1939 it was discovered that under neutron bombardment, uranium atoms could split in a process named “fission.” The immense amounts of energy released in this process could generate power but could also make a powerful bomb. The two scientists who discovered fission worked in Nazi Germany. Fearing the Nazis would build an “atomic bomb” of incredible destructiveness, physicists – including Albert Einstein – wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt warning of the potential threat.

In response, Compton became chair of the National Academy of Sciences’ Committee to Study the Military Potential of Atomic Energy. In 1942, Compton, then at the University of Chicago where he was director of the Metallurgical Laboratory, oversaw the first self-sustaining atomic chain-reaction proving that an atomic bomb was feasible. It was Compton who appointed Oppenheimer the task of designing the atomic bomb. When the Manhattan Project came under the command the US Army engineer General Leslie Groves, it was Compton again who pushed for Oppenheimer to remain the leader of the construction and testing of the bomb.9

So in July 1943, it was to Compton’s summer cabin, beside Lake Otsego in Michigan, that Oppenheimer rushed to the secret meeting warning that an atomic bomb might blow up the entire world.10

When Compton recalled this meeting later in interviews with reporters or in speeches before the public, he would tell the story as an analogy for the present. He warned that the world was in the midst of another chain reaction using words mirroring those attributed to Oppenheimer in the movie. On one of these occasions, Compton said:

“We are in an arms race of unprecedented vigor. …The conditions are thus like those of a chemical reaction in which each stage of the reaction releases more energy than the previous stage, building up until either the fuel is exhausted or the container is burst by the growing violence of the reaction – in other words, an explosion. This is a realistic description of the present state of human society as viewed by a scientist.”11

But, unlike the movie which ends on Oppenheimer’s fear of world-wide catastrophe, Compton grappled with a solution. Over a number of personal appearances and writings, he would lay out his thinking. In a 1955 editorial, he wrote, “The extraordinary state of tension in today’s world should impel us to work the harder toward establishing a peace with freedom. There is sound basis for hope. But that hope will become reality only if we do our part toward building a social order that is worthy to survive.”12

At the heart of his alternative to catastrophe were these key principles: international cooperation; the acceptance of the dignity and worth of every person; and that the wealth of the world be shared equitably. If society was dedicated to these principles, there would be a chance for lasting peace. Still, Compton realized that these ideals were easy to state, but “difficult in practice.”13

While he grew in his hope that peace was achievable, he reflected on one particular challenge that clearly exasperated him. After one event in which several speakers, himself included, spoke of these ideals necessary for world peace, he was dismayed that American media coverage made no mention of them. He noted that, “If any of the speakers were trying to transmit a hopeful vision, those who represented the nation’s eyes and ears were unconcerned with that vision.”14

Nevertheless, even in the face of what he regarded as cynicism, he offered encouragement to those who saw the possibility of peace.

“Ideas such as these need to be worked over by all who are concerned for the future of man. Only thus can the ideas take root and grow. They need to be discussed. Perhaps some of the ideas are wrong or inadequate to the need. If they are, let’s say so. Some of the ideas may inspire in us new and better thoughts. …

“I would make this request of you, …If you find inspiring vision anywhere, tell us about it. Interpret it through your own medium, so that we may share it with you. … Give us your vision, that our people may not perish but live!”15

- Scene of J. Robert Oppenheimer, portrayed by actor Cillian Murphy, walking the streets of Los Alamos. Still from the motion picture. Oppenheimer. Directed by Christopher Nolan, performances by Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr., Syncopy, Atlas Entertainment, Universal Studios, 2023 ↩︎

- Scene of J. Robert Oppenheimer, portrayed by actor Cillian Murphy, meeting with Albert Einstein, portrayed by actor Tom Conti. Still from the motion picture. Oppenheimer. Directed by Christopher Nolan, performances by Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr., Syncopy, Atlas Entertainment, Universal Studios, 2023 ↩︎

- Overbye, Dennis. “Christopher Nolan and the Contradictions of J. Robert Oppenheimer.” July 20, 2023. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/20/movies/christopher-nolan-oppenheimer.html ↩︎

- Rhodes, Richard. Quoted in: McAndrew, Tara McClellan. “Subterfuge in the City: How Illinois Helped Create the Nuclear Age.” November 29, 2019. Illinois Public Media. https://will.illinois.edu/news/story/subterfuge-in-the-city-how-illinois-helped-create-the-nuclear-age ↩︎

- Studio portrait of Arthur Holly Compton, circa 1953. Bernard Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine. https://beckerarchives.wustl.edu/VC410-S03-ss066-i02 ↩︎

- Erik Henriksen, Erik. “Arthur Compton and the mysteries of light.” Physics Today, December 1, 2022, 75 (12), pages 44-50. https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.5139 https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/article/75/12/44/2848613/Arthur-Compton-and-the-mysteries-of-lightFor ↩︎

- “Solvay Conference.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 8 March 2024 last updated. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solvay_Conference ↩︎

- Edited photograph of 5th Solvay Conference group portrait. Original: 1927 Solvay Conference on Quantum Mechanics. Photograph by Benjamin Couprie, Institut International de Physique Solvay, Brussels, Belgium. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 14 September 2012 uploaded. ↩︎

- Compton, Arthur H. “Re: Evidence Regarding Loyalty of Robert Oppenheimer,” April 21, 1954. Reprinted in: The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton. Edited by Marjorie Johnston. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1967. ↩︎

- Pearl S. Buck, “The Bomb–The End of the World?” American Weekly, March 8, 1959, pages 8-11. http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2015/ph241/chung1/docs/buck.pdf retrieved 2024-03-10 ↩︎

- Compton, Arthur H. “Give Us Vision!” An address made at the National Book Awards, March 3, 1959. Reprinted in: The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton. Edited by Marjorie Johnston. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1967. ↩︎

- Compton, Arthur H. “World Tension and the Approach to Peace.” Editorial, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1955. Reprinted in: The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton. Edited by Marjorie Johnston. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1967. ↩︎

- Compton, Arthur H. “Give Us Vision!” An address made at the National Book Awards, March 3, 1959. Reprinted in: The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton. Edited by Marjorie Johnston. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1967. ↩︎

- Compton, Arthur H. “Give Us Vision!” An address made at the National Book Awards, March 3, 1959. Reprinted in: The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton. Edited by Marjorie Johnston. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1967. ↩︎

- Compton, Arthur H. “Give Us Vision!” An address made at the National Book Awards, March 3, 1959. Reprinted in: The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton. Edited by Marjorie Johnston. Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1967. ↩︎