The bizarre contents, bizarre-er claims and bizarro ads of Ayer’s Pills

The @BeckerLibrary Archives and Rare Books team has been mad for Mondays with our weekly Instagram hashtag #MedicalAdMonday. Some highlights include an ad for Dandrine Scalp Tonic, featuring elves industriously growing a garden of hair for what appears to be a well-dressed demon, and an ad for Ray’s Germicide with—what else?—an angel subduing a storm of rather cute skeletons. They’re fundamentally fanciful, but at least the ads illustrate what the products are supposed to do.

Not so for our ad this week!

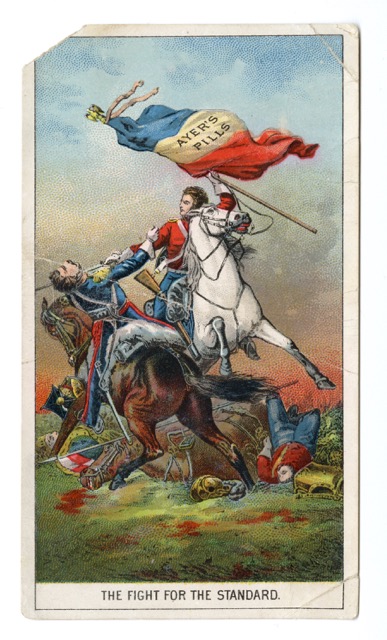

This trade card advertisement for Ayer’s Pills, produced about 1890, features a soldier doing nothing less than drive-by decapitating his enemy with one hand. With a steely-eyed sneer, he bursts forth from the furor of battle on his pristine white steed and thrusts a massive red, white and blue flag for Ayer’s Pills toward the heavens. “THE FIGHT FOR THE STANDARD” the caption declares!

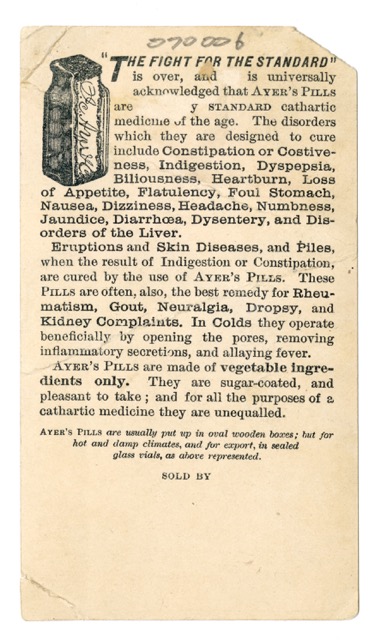

Between the name (truly opaque) and the illustration (truly terrifying), this ad not only epitomizes old-timey toxic masculinity, it spits in the eye of fanciful depiction and puts a stake in the heart of logical metaphor. For most modern audiences trying to figure out what this ad is peddling, the back of the card may only cause further bewilderment: The ad describes the product as a “cathartic medicine” and claims it will cure more than twenty-five different ailments, including Biliousness, Constipation, Dropsy, Eruptions, Flatulency, Gout, Heartburn, Inflammatory secretions, Jaundice, Kidney complaints and Loss of appetite. It’s apparently also helpful for headaches, though likely not if Bizarro Prince Charming has already removed your head for you.

So what were Ayer’s Pills and did they work? Can the contents provide any context at all for this ad?

A Peak inside the Package: What Were Ayer’s Pills?

As the medicos amongst us may have already guessed, Ayer’s Pills, sometimes called Ayer’s Cathartic Pills, were similar to a laxative. Today, the word cathartic typically refers to emotional relief, but it was originally a medical term referring to a physical purging of the body, especially the bowels.

Cathartics were an important part of medical treatment throughout the 19th century and were actually one of the best-selling types of patent medicines. In addition, as we can see from this ad, they were recommended (and used!) seemingly without discretion. But why? Why take a cathartic for everything from dyspepsia to dropsy?

Simply put: people believed that the proof was in the pooping.

As mentioned in an earlier blog on patent medicines, Americans in the 1800s had a very different understanding of disease than we do now. Up until the end of the century, both physicians and the general public believed that all diseases were the result of a single issue: an imbalance in the body between input and output, or “nutriments and excrements.” People believed that the way to restore balance, and one’s health, was by regulating secretions such as blood, sweat, urine and feces.

At a time when there were few diagnostic tools available beyond the senses, it makes sense that laypeople and doctors alike placed such importance on what went into the body and what came out. Phenomena like perspiration, pulse, menstruation, blisters, urination and defecation provided clues to what might be happening inside the otherwise inscrutable body. In this context, a drug that provided observable results, such as episodes of extreme excretion, was seen as effective.

A Dose of Data: Did the Pills Actually Work?

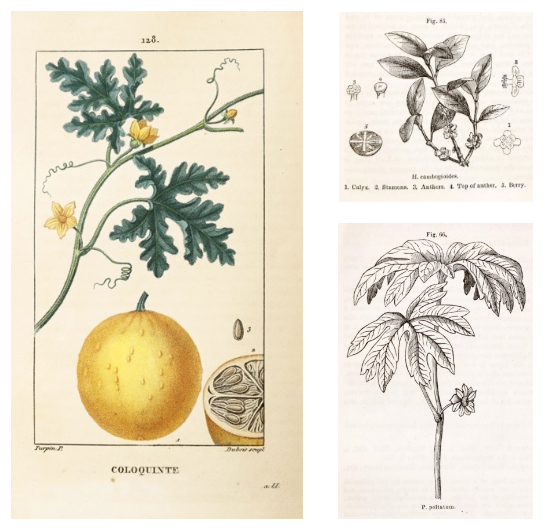

Did Ayer’s Pills work as a cathartic? Almost certainly. While we can’t know for certain if the label was accurate, packages of Ayer’s Pills produced about 1917 listed jalap, ginger, aloes, colocynth pulp, podophyllin, gamboge, oil peppermint and oil spearmint as ingredients.1 With the exception of ginger, peppermint and spearmint, they all act as purgatives, many with violent effects.

The pills were likely relatively safe to take, especially in comparison to cathartic medicines that were produced in the early 19th century. Calomel, a form of mercury, was often used as a cathartic as part of “heroic” medicine; however, by mid-century patients and physicians were starting to reject the heavy use of harsh purgatives and the extreme bloodletting advocated by practitioners of heroic medicine. Patent medicine manufacturers used this shift to their advantage and, as seen in the ad, promoted the use of mild “vegetable ingredients” in their products.

This isn’t to say that you would want to take Ayer’s Pills today, and especially not as often as the Ayer’s Company would have recommended. The drastic bowel movements caused by the pills’ ingredients could have led to intestinal irritation. Some of the ingredients also had rather unpleasant side effects. Podophyllin, also known as Mayapple, and gamboge can cause death if taken in large doses. On the other hand, taking colocynth, also known as bitter gourd, only carries the danger of poisoning.

But what about that list of conditions as long as a CVS receipt? Outside of causing a bout of catharsis or death from overdose, could Ayer’s Pills really cure an alphabet’s worth of ailments?

The answer is actually a little more complicated than you might think. While Ayer’s Pills certainly would not have cured neuralgia or numbness, they might have helped with nausea. Two of the drug’s ingredients, ginger and peppermint oil, have been found to help with nausea and flatulence. Whether or not you could have gotten a big enough dose of either ingredient without being poisoned by the colocynth (or dying from the podophyllin and gamboge…) is an open question.

That being said, assuming you weren’t taking enough to accidentally overdose, or seriously irritate your intestine, the pills might have had positive effects as an early food supplement. A study analyzed a package of Ayer’s Pills from the collections of the Henry Ford Museum using energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. Their analysis found the pills actually contained small amounts of elements necessary to the human diet: Iron, sulfur, potassium, calcium, copper, and zinc.

Not too bad for a patent medicine that caused a battle in your bowels and voiding as violent as its advertising.

Sources

- Chaumeton, François-Pierre. Flore Médicale, Vol. 3. Paris: Imprimerie de C.L.F. Panckoucke, 1833.

- Cowen, David L. and William H. Helfand. Pharmacy: An Illustrated History. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1990.

- Debevec-McKenny, Evan; Jake Ryan; Ursula Florjanczyk; and Robyn Hughes. “Laxatives and Cathartics.” Osmosis.org. Accessed April 15, 2022. osmosis.org/learn/Laxatives_and_cathartics

- Diefenbach, Andrew; Danielle Garshott; Elizabeth MacDonald; Thomas Sanday; Shelby Maurice; Mary Fahey; and Mark A. Benvenuto. “Examination of a Selection of the Patent Medicines and Nostrums at the Henry Ford Museum via Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry.” In Chemestry of Food, Food Supplements, and Food Contact Materials: From Production to Plate, 87-97. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society, 2014.

- Estes, J. Worth. “The Pharmacology of Nineteenth-Century Patent Medicines.” Pharmacy in History 30, no. 1 (1988): 3-18.

- Griffith, R. Eglesfeld. Medical Botany: Or, Descriptions of the More Important Plants Used in Medicine: With Their History, Properties, and Mode of Administration. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847.

- Haller, John S., Jr. “Samson of the Material Medica: Medical Theory and the Use and Abuse of Calomel in Nineteenth-Century America, Part I.” Pharmacy in History 13, no. 1 (1971): 27-34.

- Lewis, Walter H. and Memory P.F. Elvin-Lewis. Medical Botany: Plants Affecting Human Health. 2nd ed. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. “The Therapeutic Revolution: Medicine, Meaning, and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century America.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 20, no. 4 (Summer 1977): 485-506.

- Street, John Phillips. The Composition of Certain Patent and Proprietary Medicines. Chicago: American Medical Association, 1917.