Medical knowledge has undergone, shall we say, significant changes since the medieval and early modern periods. Humorism – the idea that the bodily health depended on the proper balance of the four humors of blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile – has been thoroughly debunked. We understand germ theory. A broken bone is a very treatable medical condition. The medical landscape that existed several centuries ago is now strange and unfamiliar to us – or is it?

One medical condition that a lot of us worry about is cancer. In response to this concern, the Siteman Cancer at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine provides its 8 Ways to Stay Healthy and Prevent Cancer as a practical guide for healthy living that can help reduce risk factors. This advice is firmly rooted in common sense. Getting regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, and drinking alcohol in moderation are all straightforward recommendations that can help reduce potential health complications.

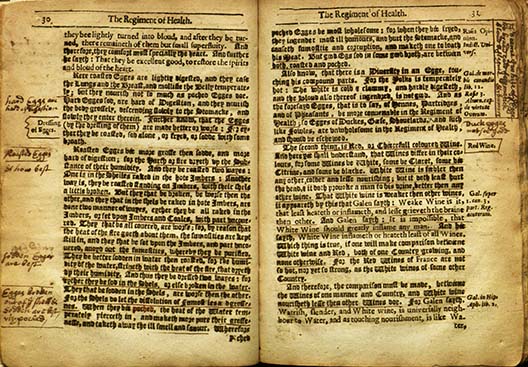

People living in the 17th century didn’t have an eight-step program to guard against cancer, but they did have the Salernitan regimen of health, a didactic poem that served as a guide to healthy living. It was derived at least in part from the teachings of a medical school located in the Italian city of Salerno, the most famous site of medical learning in medieval Europe. The regimen began circulating in manuscript form during the medieval period and proved enduringly popular – the first printed edition appeared in Latin in 1480, and vernacular editions were printed throughout the early modern period. Becker Library’s rare book collections hold a 1500 Latin edition and a 1634 English edition. The English edition is heavily annotated, hinting that a previous owner referred to it frequently.

What kind of health advice did this regimen offer? Like all medicine at the time, it was focused around keeping the humors in balance. Large swaths of the regimen’s recommendations are obsolete today – the ones that focus on bloodletting come to mind – but others are rooted in common sense. The regimen’s central tenant is as follows:

Shun busie cares, rash angers, which displease;

Light supping, little drinke, doe cause great ease.

Rise after meate, sleepe not at after-noone,

Urine, and Natures need, expel them soone.

Long shalt thou live, if all these well be done.

Translated into modern English, this basically boils down to avoiding stress, not eating and drinking to excess, and not sleeping right after eating. This is pretty straightforward advice, and while it’s not groundbreaking, it’s also not going to do any harm.

One of the most important components of the regimen is diet, and how it can be used to maintain the balance of humors. While some of this advice seems a little strange now – for example, it warns against eating bread crusts because their dryness can cause a choleric state (perhaps a centuries-old justification for removing the crusts from PB&Js?) – some of it remains as sensible today as it was hundreds of years ago. When it comes to drinking wine, the regimen says the following:

Often, yet little, drinke in dinner-time,

But betweene meales, you must from drinke decline,

That sicknesse may in power lesse preuayle,

Which else (through drinking) sharply doth assayle.

Although it’s written in an archaic style, this advice is doubtless familiar to all of us: drink alcohol in moderation!

The question of how to live a healthy lifestyle will no doubt persist throughout history, and will continue to evolve as our understanding of medicine becomes more comprehensive. Chances are, however, that some pieces of medical advice will never go out of style.