A fountain pouring blood instead of wine. A blood-red moon and blood raining from the sky. The capture of a fish that looks like a lion. What do these unsettling events portend? The answers can be found in a compilation of early modern religious propaganda by the German preacher Heinrich Oraeus (1584-1646). Oraeus was a proponent of the religious reformation that swept through Western Christendom following, and this work has a strong anti-Catholic bent—with no greater source of his religious ire than the Pope, whom he refers to as the Antichrist.

The Antichrist has occupied a prominent place in Christian thought almost from the religion’s inception. While the term only appears a handful of times in the New Testament’s Johannine Epistles, the Antichrist still came to hold a prominent position not only in religious belief, but in Western cultural milieu. Anxiety about the Antichrist’s appearance tends to coincide with periods of unrest and instability, and the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe were particularly chaotic. The Reformation continued to cause divisions among communities, particularly in German-speaking countries, a situation that was further inflamed by the Thirty Years’ War. It is not surprising that Reformist factions saw this heightened atmosphere as an opportunity to attack the Papacy by casting it as the Antichrist.

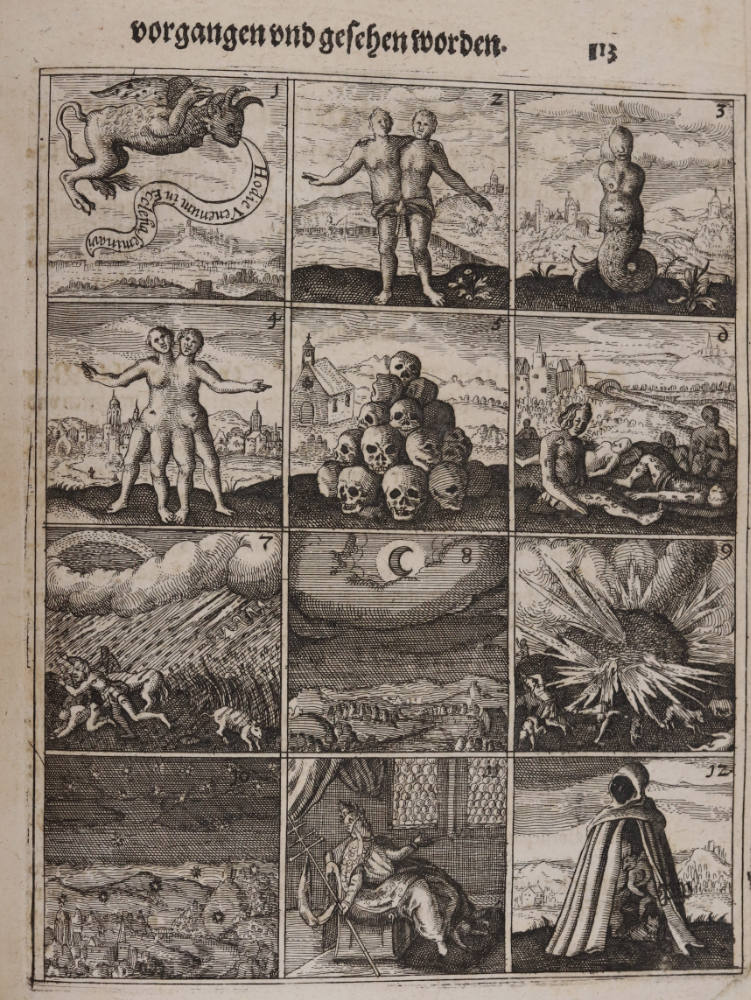

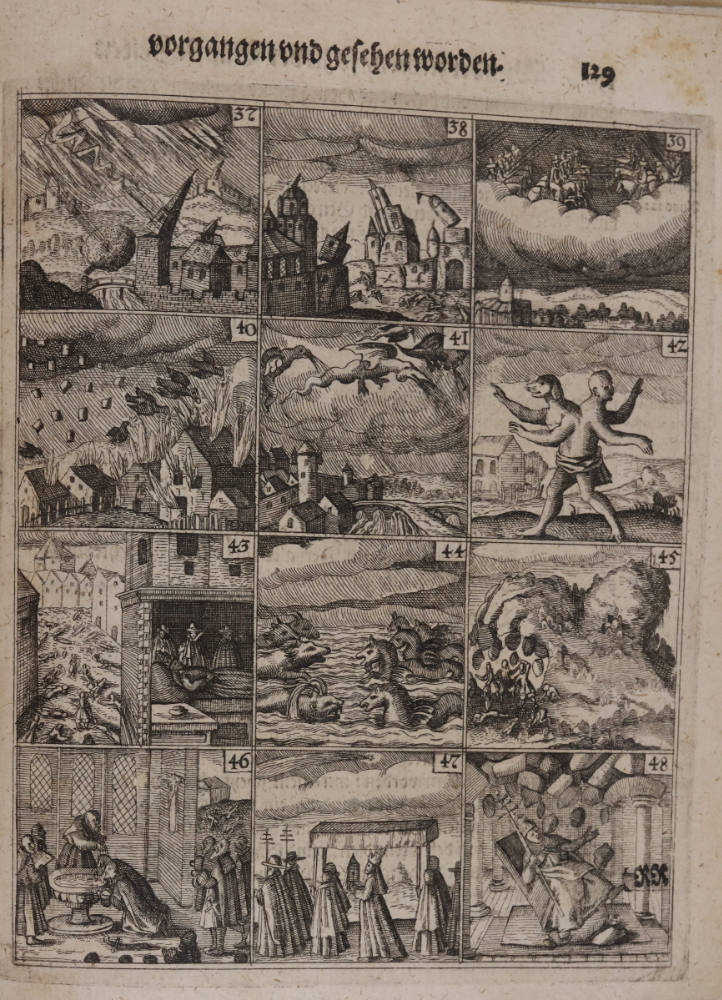

The Antichrist’s arrival was heralded by various uncanny events. These could make for sensational reading, and early modern printers provided the public with a number of cheap pamphlets on comets, monstrous births, and other ominous portents. The final section of Oraeus’s tract falls into this genre. The title roughly translates to “Of the wondrous signs and wondrous works, and also wondrous births, which are seen during the times and reigns of the godless Roman popes,” and the contents deliver on this promise. This section contains six engraved pages divided into 12 squares each, with these small squares containing an image of an ill omen that was explained by the text. For example, the moon in Square 8 has gone dark and is shining with blood-colored light, which happened in the year 683 during the reign of Pope Leo II as a sign of his “tyrannical reign.” Meanwhile, Square 40 depicts events in the year 1224, when Dominicans from Italy arrived in England. Their arrival was accompanied with extreme weather events such as hail shaped like squares and as large as eggs, and the appearance of birds that carried glowing coals in their beaks and set houses on fire.

Certainly, a number of these events were not supernatural portents, but just natural phenomena that early modern science couldn’t explain. A moon going dark can easily be seen as an eclipse, unusual birth defects have occurred throughout history, and catastrophic natural disasters take place regardless of who holds power. But one aspect about the idea of the Antichrist—and about prophecy in general—is that it is highly adaptable to any time period. What images would you put in a book of wonders and marvels to reflect chaos and uncertainty in your own life?

For more information on prophetic writings of the early modern period, see our virtual exhibit Prophetic Illustration in the Paracelsus Collection.