Be sure to bundle up well this winter to avoid getting sick and catching a cold! While this common ailment has no cure, that hasn’t stopped people throughout history from coming up with ways to alleviate their sniffles, coughs and all other cold-related discomforts. In his work The book of health, Dr. Silas Wilcox described the common cold as “the exciting cause of nearly ‘all the ills to which flesh is heir.’”

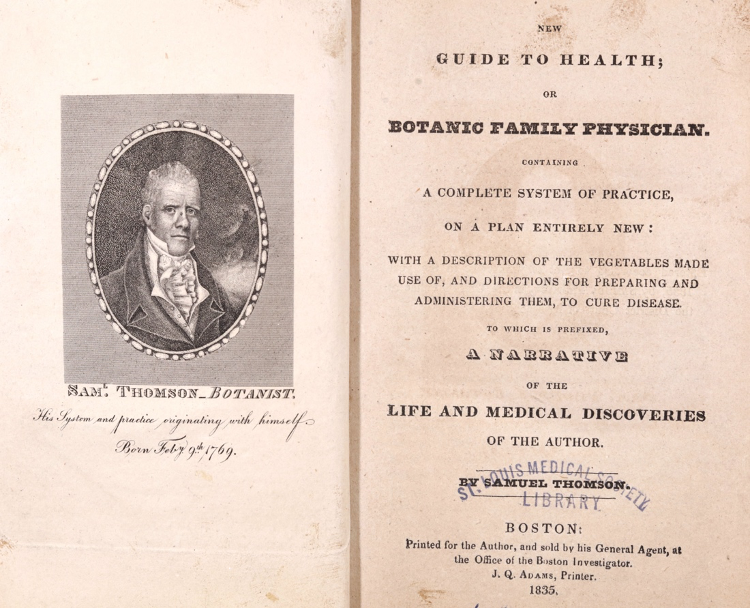

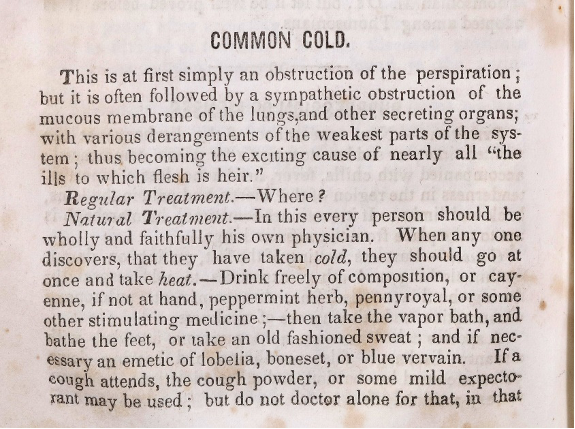

Wilcox was an adherent to the Thomsonian school of medicine, a nineteenth-century American herbalist movement named after its founder Samuel Thomson (1769-1843). As a Thomsonian, Wilcox would prescribe a drink of cayenne peppers, peppermint herbs, pennyroyal, “or some other stimulating medicine” for those afflicted with a cold. After the drink, the patient should “take the vapor bath, and bathe the feet, or take an old fashioned sweat.” In true Thomsonian fashion, this was followed by an emetic (a mix that induces vomiting) of lobelia, boneset, or blue vervain. The patient was advised to repeat the process every evening until well, “remembering to steam thoroughly, sleep warmly, and be careful the next day.”

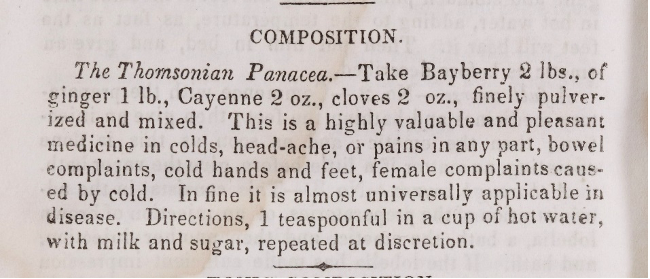

The herbs and plants in the listed remedies would be familiar to anyone familiar with Thomson’s system. The stimulating herbs that Wilcox mentions (such as cayenne, peppermint, or pennyroyal) were considered vital in staving off illness, which Thomson believed was caused by cold. It was thought that a person could only recover by restoring the body’s natural heat.

Thomson also heavily advocated for the use of lobelia, a plant whose discovery and medical attributes he mainly attributed to himself (and a claim that was refuted by some of his contemporaries). The plant was a favorite of his and a signature of his medical system. He described it as “of great value in preventing sickness, as well as curing it.” Much like modern “cleanses,” the vomit-inducing properties of lobelias were believed to invigorate patients after emptying their stomachs of “every thing that nature does not require for the support of the system,” leaving them with “a full flow of vigor and spirits.”

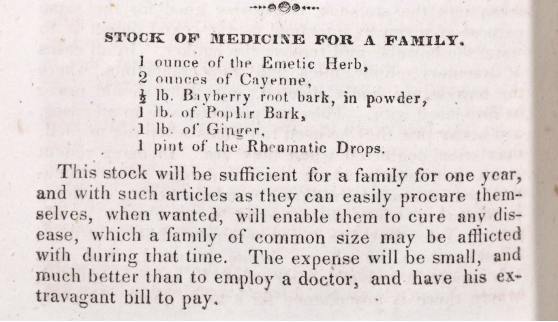

These herbs and remedies were easily accessible to the average person, and it was in this manner Wilcox and Thomson advocated for each layperson to be their own doctor. This sentiment formed the core of Thomsonian medicine. Using the Thomsonian system of herbs, one would be able to cure all their ills at home instead of relying on professional physicians, which those under Thomson’s banner both disdained and distrusted.

The preface of Thomson’s published A New Guide To Health, written “by a friend,” denounces medical training as nothing more than years spent “learning the Latin names of the different preparations of medicine” and “different parts of the human body, with the names, colors and symptoms of all kinds of disease, divided and subdivided into as many classes and forms as language can be found to express.” As a result, these doctors-in-training only gain enough experience and practical knowledge to know “how much poison can be given without causing immediate death.”

Thomson believed that not only were people able to sufficiently cure themselves through the use of botanic knowledge, thereby denoting medical training as unnecessary, but also that trained physicians were actively poisoning their patients through the injections of mercury and arsenic and the practice of bloodletting. Rather than thinking that doctors were simply misguided, however, he believed that these practices were a malicious and deliberate attempt to sicken their patients, as “it is for the interest of the doctor, if the family is not sick, to make them so.” Although untrue, distrust of medical professionals persists throughout history, even long after the Thomsonian system fell out of practice.