Modern medical texts tend to be straightforward in their content, presenting the necessary information without artistic embellishment. Their medieval and early modern counterparts, however, made ample use of visual allegory. We’ve already talked about several famous examples, such as Vesalius’s evocation of classical statuary and the various Greco-Roman deities tucked into frontispieces, but today we’re going to dive into one of the most famous early artistic motifs: the Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death.

The first artistic representation of the Dance appeared as a mural in Paris’s Holy Innocents Church in 1425 (sadly, this is long since destroyed). Depictions of Death dancing with people from all social classes soon appeared on the walls of other churches from London to Basel, and shortly thereafter made the leap to metalwork, manuscripts, and printed books. While this macabre imagery might have roots in medieval drama, another reason for its appearance was undoubtedly the catastrophes that had so recently befallen Europe: famine brought on by the Little Ice Age, the Hundred Years War, and, of course, the Black Death.

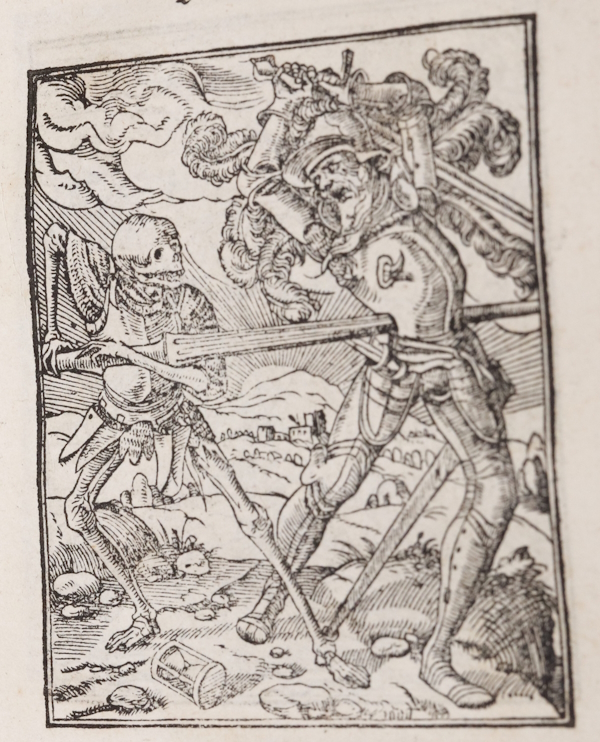

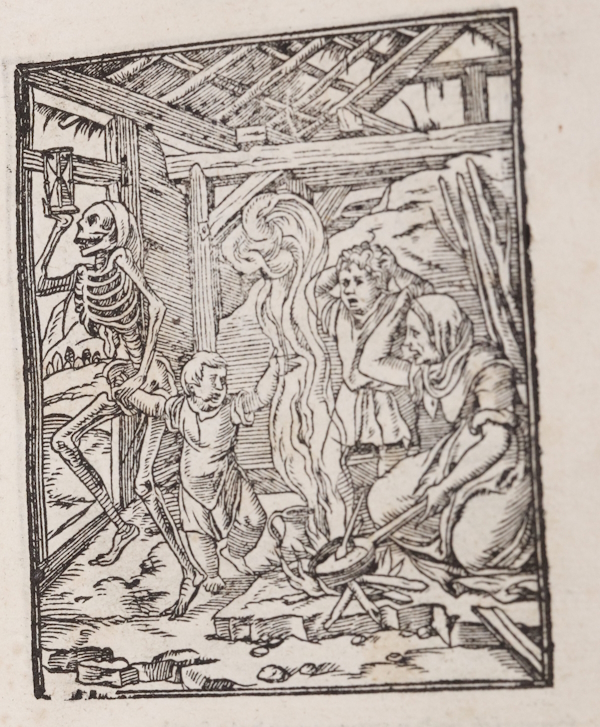

The most famous iteration of the Dance is perhaps the series of woodcuts created by Hans Holbein (1497-1543), one of the 16th century’s most renowned artists. His series of beautifully detailed illustrations show how various personages react to the presence of Death before them. These range from (grim) acceptance—the Old Woman, weary with life, follows a skeleton playing a musical instrument—to terror—the face of the Nobleman is contorted with fear as Death runs him through with a sword—to despair—a mother and child cry out in grief as Death leads their child away by the hand.

The Todtentanz edition held by Becker Library is a close copy of the Holbein version, although the illustrations are mirror images of Holbein’s originals. Each image is accompanied by a quotation from the Vulgate Bible, and the remaining text comes from the French printer Gilles Corrozet’s The Images and Storied Aspects of Death. The theme of Corrozet’s text is predictably bleak: Death will come for us all, regardless of social status, and no amount of pleading can stay its approach.

And why exactly is a copy of an artistic work such as this at the medical library? For one thing, it is bound together with another work consisting of texts that focus on how one should console those who are sick and dying. Death has always gone hand in hand with medicine, and the question of how to talk about the end of life is a key concern of physicians. Furthermore, cultural context is an important aspect of studying the history of any subject. Woodcuts such as these can provide insight into how people hundreds of years ago thought about the presence of death in their lives and attempted to cope with that knowledge—one of the most enduring themes in the history of the world.