This work is disrespectfully dedicated to those who feel that a knowledge of the Human Body, sufficient for the needs of the future Medical Practitioner, can be adequately obtained without post-mortem investigation. It will be seen that with the aid of a few objects borrowed from the gardener, or cook (if she be out), the salient features of Human Anatomy can be brought home to the Student’s mind in the drawing-room, the larder, or the wine-cellar.

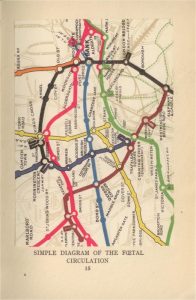

So begins the preface to Astonishing Anatomy by Tingle, a humorous and irreverent take on medical guides for students. A brief review in Volume 1, Issue 2716 (March 29, 1913) of the British Medical Journal describes the work as, “very good fun” while also acknowledging that it has little, if anything, to do with anatomy. That is certainly an accurate assessment. For example, the chapter titled “A Condensed Conversation” is a dialogue between “a discontented Spanish Hidalgo suffering from a slight peristaltic hitch and an asthmatic Armenian Apothecary learning Esperanto,” and is fairly incomprehensible. Even the segments that seem to be more explicitly medical make no real attempt to be accurate – Tingle’s diagram of the fetal circulatory system is certainly not useful from an anatomical point of view, although it might have been useful for a tourist visiting London in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Yet as the BMJ puts it, “the author, whose portrait we do not recognize, shows by his title-page that he has some acquaintance with German literature and that, however eccentric his views on anatomy, he has some knowledge of the proceedings of the Anatomical Association of Great Britain, Ireland, ‘and especially Scotland.’” Unlike the rest of the publication, this is actually true. Tingle was the pseudonym of Samuel Ernest Whitnall (1876-1950), an English physician and anatomist who was particularly well-known for his work on orbital anatomy. He began his medical career by working as the Demonstrator of Anatomy at Oxford University, then served as a medical officer in France during World War I. In 1919 he accepted a position at McGill University in Canada, where he remained until he became Chair of Anatomy at Bristol University in 1935. He retired in 1941, and passed away in 1950.[i]

Yet as the BMJ puts it, “the author, whose portrait we do not recognize, shows by his title-page that he has some acquaintance with German literature and that, however eccentric his views on anatomy, he has some knowledge of the proceedings of the Anatomical Association of Great Britain, Ireland, ‘and especially Scotland.’” Unlike the rest of the publication, this is actually true. Tingle was the pseudonym of Samuel Ernest Whitnall (1876-1950), an English physician and anatomist who was particularly well-known for his work on orbital anatomy. He began his medical career by working as the Demonstrator of Anatomy at Oxford University, then served as a medical officer in France during World War I. In 1919 he accepted a position at McGill University in Canada, where he remained until he became Chair of Anatomy at Bristol University in 1935. He retired in 1941, and passed away in 1950.[i]

His most famous medical work was his Anatomy of the Orbit (1921), but his literary talents were not restricted to the scientific realm. Even before he published Astonishing Anatomy Whitnall-as-Tingle wrote columns for Punch, a British magazine that specialized in humor and satire.[ii] In 1932 he published The Architectonics of the Monogamal Oestrous Cycle in the Greater Pifflecock (Gallinopunk Gigas Occidentalis) under the name “Stodge D. Loquax of the Wishful Destitute of Anatomy. Pah;” however, this satirical piece was not well received.[iii] But one man who seemed to appreciate Whitnall/Tingle’s British sense of humor was the St. Louis ophthalmologist James Moores Ball – our copy of Astonishing Anatomy from the Ball Collection is inscribed, “To Dr. J Moore Ball from the author. Montreal Sept. 15 1924.”

[i] “In Memoriam: Samuel Ernest Whitnall, M.A., M.D., B.Ch (Oxon.), M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. (Lond.),” Journal of Anatomy Vol. 84, No. 4 (1950): 394.2 – 396.

[ii] Horace Mayhew and George Cruikshank, who created the dental satire The Tooth Ache, were also involved with Punch magazine: https://becker.wustl.edu/about/news/charming-side-dental-check-ups

[iii] “In Memoriam,” 396.