Prior to the development of antibiotics and aseptic surgical techniques, surgery was a fraught prospect. Not only would the patient have to contend with the pain and trauma of the procedure itself (carried out without the benefits of modern anesthesia), but the risk of postoperative infection was high. Despite the inherent dangers of early modern surgery, sometimes there were no other viable options. Since June is Cataract Awareness Month, we’ll be taking a closer look at one of the most common surgical operations of the early modern period: couching a cataract.

Cataracts are a cloudy portion on the lens of the eye that cause blurred vision. They are a common ailment among the elderly, so it is not surprising that treating them was an important skill for surgeons. While early modern medical practitioners usually prescribed treatments such as vapor baths, plasters, and diets to cope with cataracts in the early stages, at a certain point surgical intervention was necessary. This usually meant couching, a procedure in which a sharp needle is used to push the cataract back into the vitreous portion of the eye. While this did not remove the cataract, it allowed light to enter the eye, which might have provided a modicum of relief, although the outlook was poor.

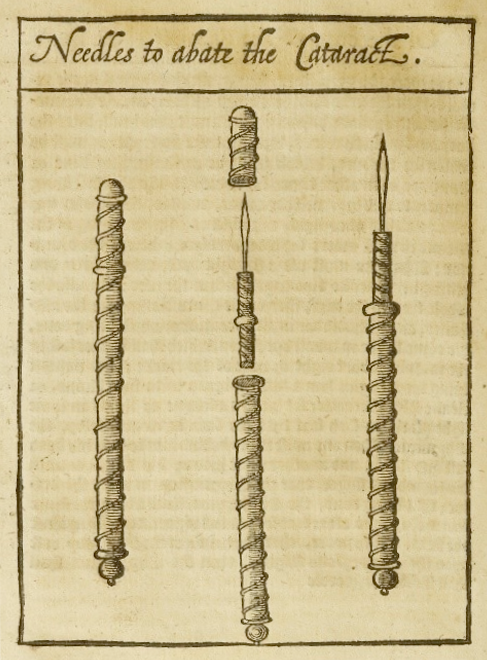

In his 1583 text Augendienst (Service of the Eyes), German oculist Georg Bartisch describes the process in great detail. Having the correct equipment was important, and he recommends that the needles be made from “good and fine silver and not from brass, steel or iron. The point should be smoothed and sharpened, and preferably gold plated.” The patient should be purged two days prior to the operation, and the day of the surgery the patient should keep their stomach as empty as possible until an hour after the surgery. It should take place in a chamber with good lighting (absolutely not outdoors, which is what the quack doctors would do!), and the physician should position himself slightly higher than the patient. The patient should move the afflicted eye a bit toward their nose, then the surgeon inserts the needle at the edge of the cornea and carefully works the cataract downward. This procedure was fairly standard. The renowned 16th-century surgeon Ambroise Paré describes a similar process — although he recommends the needles be made from iron or steel — as does the Scottish surgeon Peter Lowe, who established a professional organization of surgeons in Glasgow.

Some of the surgeons’ instructions might strike our modern sensibilities as strange. For instance, Bartisch advises physicians against conjugal deeds for two days and nights prior to the operation, and no women should be present or allowed to observe the operation. Peter Lowe’s instructions for preparing the eye recommended that “a child who hath sweet breath shall chew synamon, ginger, cloves, or fennel, and spit it out, and breath three or foure times in the eye of the sicke.” And Paré reminds his readers to take the heavens into account, and perform the operation “in the decreas of the moon … and when as the Sun is not in Aries, because that sign hath dominion over the head.” While Bartisch’s anxiety about women seems rooted in superstition, Paré’s advice underscores the close connection between astrology and medicine in the early modern world.

Today, most cataracts are treated by removing the lens entirely and replacing it with an artificial one. Couching is, however, still practiced in parts of the developing world where access to trained ophthalmologists and surgical techniques remains limited.

References

Ambroise Paré. The Works of that famous chirurgion Ambrose Parey. London: Printed by Richard Coates, 1649.

Peter Lowe. A Discovrse of the VVhole Art of Chyrvrgerie. London: Printed by Thomas Pvrfoot, 1634.

Georg Bartisch. Ophthalmodouleia. Translated by Donald L. Blanchard, M.D. Belgium: Wayenborgh, 1996.