When World War I began in 1914, American public opinion was divided about whether the U.S. should get involved. But by 1917, it was clear that U.S. involvement was inescapable. In early April 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. With a great show of public enthusiasm, support for the troops became a rallying point and a way for Americans to express their patriotism. Thousands of Americans enlisted in the armed forces or volunteered for some other role in the war effort, though they may not have anticipated how the war would impact their lives and the world.

In St. Louis, one focus of the volunteer effort was Base Hospital 21, an Army medical unit organized at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Base Hospital 21 was a result of a plan begun in 1916 by the American Red Cross and the War Department to prepare a number of base hospitals. These units were developed from existing medical schools and hospitals so that if the United States should enter the war, fully equipped hospital units complete with physicians, nurses, and supplies would be ready for active service. Medical school faculty and students, as well as Barnes Hospital staff and nurses, volunteered for the unit.

One St. Louisan to volunteer with Base Hospital 21 was Olga A. Krieger. In May 1917, she and the rest of the unit left St. Louis amid great fanfare, bound for New York, then on to England and eventually war-torn France. Kreiger kept a diary of her experiences which is now held in the Becker Medical Library archival collections.

At the beginning of her travels, she was cheerful, writing of the “delightful” lunches she and her fellow nurses had on their journey. She wryly described her and her fellow passengers’ seasickness on the voyage across the Atlantic as “beautiful seasickness – an everlasting dream to the person who has the experience of it.”

By the time they arrived in England, she began to note the far-reaching impact of the war. Of war-time London, she wrote, “Young men are scarce. Old and disabled there were many, children and chimneys were plentiful. Conductors, chauffeurs, street cleaners, elevator boys, peanut & candy venders all positions taken by women.”

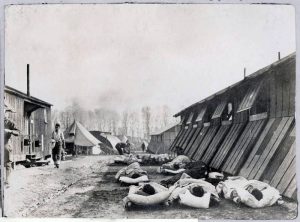

On June 10, 1917, Base Hospital 21 became one of the first groups of Americans to reach France. The unit was quickly sent forward to operate a military hospital near Rouen. There Kreiger and her fellow nurses would first learn the harsh realities of the front lines from their patients. Early on, one exhausted young soldier told her, “You don’t know what a relief it is to be able to get into a clean bed after being up in the trenches.”

Some patients Kreiger would never forget. “This poor lad could not lie on his back as he was unable to breathe but had to sit upright, his back braced up with a back rest. …with the everlasting expression of death upon his countenance, with life ebbing out of his body with each breath and still he lingered. At first he was anxious to get well though as time went on [he] thought life a burden and declared, ‘I am still young and I served my country, have done my duty as a man should, now all I want is relief and I don’t care in what way.'” He died after five excruciating days and sleepless nights.

As Kreiger continued in her diary she admitted to the sobering reality. “The dreadful war is the cause of all this torture. Men leave their homes and loved ones; are in robust health only to be disfigured, disabled, shell shocked and most gruesome of all to be blown to atoms and yet war is carried on. [I] can never forget the night when one of the nurses and I went out for a stroll a draft was going up the line and these poor unfortunates in gleeful spirits called back, ‘Save me a bed sister.’ This almost caused our blood to stand still realizing how tired the poor boys were of this terrible war and realizing what dreadful suffering with which some would have to content. Oh, how could anyone ever cherish the thought to plunge into war?”