Becker Library’s archives contain so much more than paper documents. Many of our collections comprise an amazing array of unique artifacts, including photographs and albums, clothing, plaques and medals, blueprints, historic currency, and maps. We also care for collections including materials that are incredible resources for the preservation of the history of medicine and its practice but also pose a much greater risk to those working with them than books and paper. We were recently faced with a significant challenge posed by historic pharmaceuticals stored in physician’s bags that have been in the archives since the mid-20th century and have been sitting quietly on the shelves for decades.

The potentially hazardous nature of doctor’s bags includes the physical dangers of handling sharp surgical tools or chemicals that have become explosive due to their degradation over time. Historic pharmaceuticals also contain ingredients that were once legal, i.e., cocaine, heroin, opium, but are now illegal, as well as toxic ingredients such as mercury and strychnine. Additionally, historic vaccination materials potentially contain remnants of live virus. As historians and archivists, we are dedicated to preserving the evidential and informational value of the collections in our repository, including hazardous artifacts. A vital component of an archivist’s job is cultivating relationships with donors, who entrust us with their collections under the assurance that the materials will be cared for and the information they contain will be described and made available to the public. However, keeping everything forever is impossible, and archivists are also constantly making decisions about what to keep, what to transfer to another repository, and what to discard.

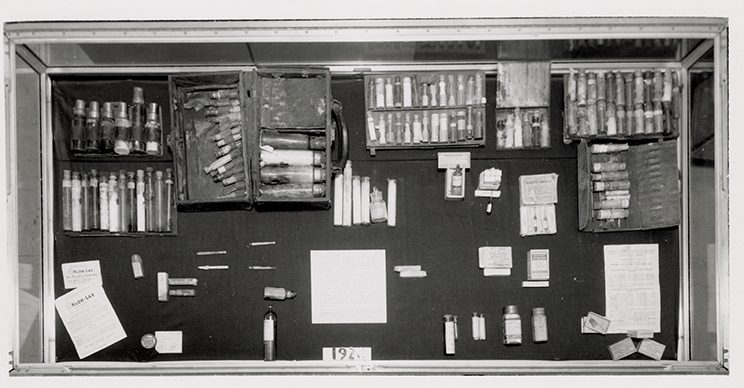

With these two collections, we had to ask ourselves several tough questions. The most important question was, of course, what is exactly is in the collections and how dangerous are they? In 1962, the WUSM library displayed the contents of the doctor’s bags – owned and used by John Green, MD, and Charles L. Lavender, MD, around the beginning of the 20th century – as part of an exhibit titled “A Doctor’s Bag Past and Present.” The purpose of the exhibit was to show how the contents of a doctor’s bag were standardized over time, beginning in the 1940’s.

Unfortunately, the documentation we have regarding the bag’s contents included photographs of the items on display with some general descriptions, but no descriptions of the drugs in vials unless they have clearly typed labels attached. After the exhibit, the doctor’s bags were placed in archival storage boxes and had been sitting on shelves in the stacks ever since.

There are two substances, in particular, we were concerned about being present in the doctor’s bags: picric acid and ether. Picric acid was often stocked in pharmacies in the early 20th century and was most often used as a burn treatment. Picric acid is flammable as a liquid and would have been stored in a bottle under a layer of water. Over time, the liquid sublimates and the dry picric crystals left in the bottle are explosive and sensitive to shock and friction. Similarly, ether that has deteriorated and crystalized over time is highly explosive.

An online resource we consulted prior to pulling the doctor’s bags out of storage was a guide titled “Hazardous Materials in Medical Collections,” developed by the Museums and Galleries of New South Wales.[1] The guide advises:

Seek expert advice. There are many experts and authorities that can offer help in dealing with particular hazards. It is a good idea to cultivate such people and organizations in your own locality and get them interested in your museum.

Remember, however, that authorities whose usual business does not involve dealing with museum objects are likely to have different priorities to yours. It is wise to weigh up their advice against what you believe are the proper purposes and practices of a museum.

Due to the age of the collections and the likelihood they contained one or both of these substances, we decided to set up an appointment with the Environmental Health and Safety department to help us inventory our doctor’s bags and assist us in the removal of items if necessary.

I first reached out to Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), because of the many intact drug kits and doctor’s bags on display in their digital collections. Their University Archivist assured me that because their collections are locked down (as are our collections), their EH&S officer saw no reason to remove any medicines, even those containing controlled substances, from their collections. Additionally, their office facilitates the disposal of any substance from compromised vials or jars and returns the clean containers to the archives afterward.

With that in mind, prior to our meeting with WUSM’s Environmental Health and Safety office, I attempted to explain that our goal was to keep the collections intact and only remove what was absolutely necessary, i.e., potential explosives. We also wanted assistance in identifying the contents of vials with scribbled, handwritten labels, or with no labels at all. We asked that if the contents of a vial or jar were considered too dangerous to keep, we’d like the container washed out and returned to the archives.

The phrase “different priorities” unfortunately turned out to be understated in our case. Some materials that were the subject of our initial concerns were indeed present in the doctor’s bags, including an empty can of ether, a vial of nitroglycerin pills, and several glass ampules containing typhoid vaccine that alarmed a Biosafety Compliance Specialist for their potential to contain live virus. Beyond the obvious need to remove these few items from the collections, and despite our protestations, over 100 other vials and jars were removed from the doctor’s bags due to their poisonous or controlled contents, or because they were unlabeled or the label was illegible. Not only were these materials unnecessarily removed and disposed of, but their containers were also not returned to us. Our EH&S department advised that they do not offer that service.

Remember, historically doctors and pharmacists prescribed and facilitated the use of many toxic substances once thought to cure illness, such as strychnine and cocaine, and these substances are safe as long as they are properly handled and not ingested. As the Museums and Galleries of New South Wales succinctly put it:

Visitors to historical displays of medicines are interested in whether the contents of jars and bottles are real, particularly whether now-illegal drugs like laudanum are real. The circumstances under which substances became prohibited form part of the history of your collection. Visitors derive a sense of satisfaction from knowing that the objects they are looking at are genuine and complete because, after all, museums are places where people come to see real things.

In the 1960’s, Becker Library displayed John Green’s and Charles L. Lavender’s doctor’s bags and all of their contents for the WUSM community and the public, and a subsequent article about the exhibit was published in the Bulletin of the Medical Library Association (now the Journal of the Medical Library Association). Over fifty years later, our attempt to maintain and properly identify the contents of these collections led to their decimation by authorities who believed that their decisions were in our best interest, or that their hands were tied by government regulations. Why was our experience with historic pharmaceutical collections so different from that of OHSU?

One reason is likely that they have many pharmaceutical collections, whereas Becker Library has only two. Archivists at OHSU have thus worked with their Environmental Health and Safety office for years, and have cultivated a relationship with the particular goal to preserve and display their collections safely and intact. Their collections still contain their original contents, including medicines with now-illegal ingredients. WUSM’s Environmental Health and Safety officers agreed not to immediately destroy vials containing controlled substances, but to first contact the DEA on our behalf. Several weeks have now passed with no word if those medicines will ever be returned. A more positive outcome has been the fate of the ampules of typhoid vaccine. Although it could not be definitively determined if the vaccines were made using live virus or not, they will still be returned to the archives once proper biosafety storage materials are delivered.

My experience with historic pharmaceuticals has been a frustrating and disappointing one. I believed that working with our Environmental Health and Safety department would not only help with the identification and safe handling of these materials but also could facilitate an updated exhibit of doctor’s bags in the Glaser Gallery. Now I am unsure if we have enough remaining artifacts for a full exhibit. A lesson I will take away from this experience is to provide more context to outside authorities prior to their visit. Perhaps if I had initially shared the guidelines written by Museums and Galleries of New South Wales and my communications with OHSU’s Archivist with our Environmental Health and Safety authorities, the outcome would have been a little different.

UPDATE 11/8/18: The fate of the pharmaceuticals containing controlled substances was just decided by the DEA – we are not allowed to keep the vials’ contents. Becker Library could have gotten back cleaned and emptied vials at the cost of $5,000, however, the cleaning process would have destroyed all of the century-old, handwritten labels. For that reason, we determined that the cost was not worth it.

[1] https://mgnsw.org.au/sector/resources/online-resources/risk-management/hazardous-materials-medical-collections/