Practitioners of humoral theory took the idea of a balanced diet to a whole new level as they incorporated the consumption of food and drink into their medical belief system. A prevalent medical practice in medieval and early-modern Europe, humoral theory has its roots as far back as Hippocrates and Galen in ancient Greece. The four humors, or bodily fluids, (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm) were a combination of four qualities (hot, cold, dry, moist) that were believed to affect temperament and physical qualities and health.

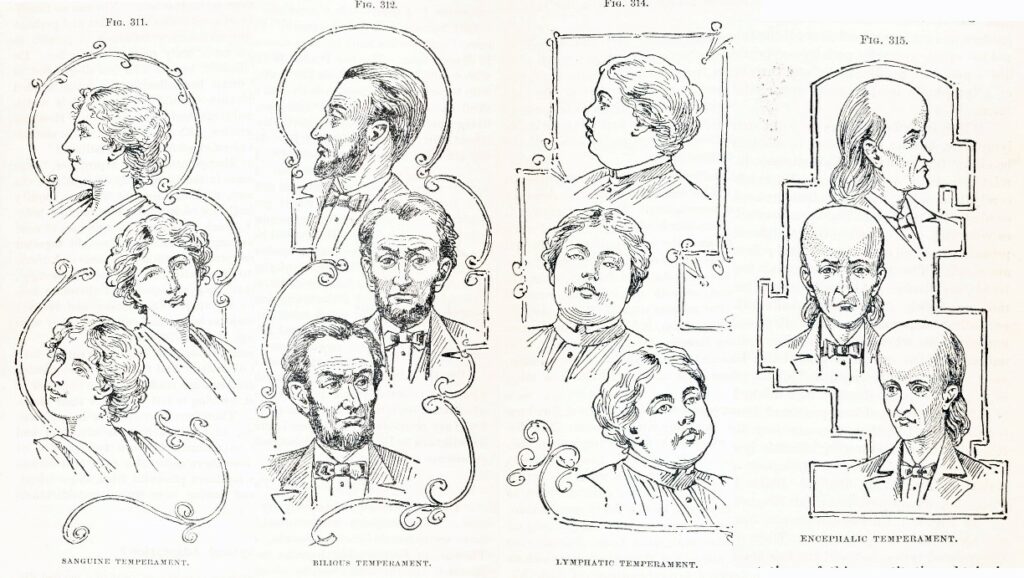

A person has one prevailing humor, which would then impact their personality and physical appearance (which was referred to as their “complexion”). People who had an abundance of blood were described as being sanguine, which meant that they had cheerful personalities and a ruddy appearance; this was in contrast to people who had phlegmatic complexions due to the dominance of phlegm in their bodies, said to have listless personalities and pale appearances. Likewise, people with dominating yellow bile were called choleric with jaundiced appearances and angry personalities, while people with too much black bile were deemed melancholic and viewed as dark in complexion but sad and creative in personality.

Image sources: Foote, Edward Bliss. Foote’s new plain home talk on love, marriage and parentage. 1901.

One’s humoral makeup could be affected by several outside factors which included diet. As a result, physicians could recommend foods safe for consumption based on a person’s health and humoral balance, or which foods would unbalance the humors in the body and should therefore be avoided. Similarly, food could also be used to treat someone by restoring their humoral balance.

The humoral qualities of food and drink were influenced by several factors, which includes elemental affinities. Just like how each humor has an associated element, different foodstuffs have humoral affinities due to their elemental qualities. Herbs could be considered to be choleric or could make food or people choleric, as herbs are leafy and thus have an air affinity and so have a “warm” quality. At the same time, they are also plants and of the earth, and are therefore also considered “dry.” Using herbs would thus be able to balance out phlegmatic foods with wet and cold properties, such as cucumbers, lettuce, spinach, fish, pork, or veal.

Image source: Hessus, Helius Eobanus. De tuenda bona valetudine, libellus. 1554.

The humoral alignment of food was also determined by the effect on the body – for example, although sugar physically feels dry, it was believed to warm and moisten the body, so it would be more sanguine. This could be tied in to the food’s flavor as well, as the flavor affected the body. Salty things tend to make people thirsty and so are seen as drying, and thus choleric foods are often bitter or salty in nature. Therefore, foods like olives, capers, and salt itself are drying and choleric.

Image sources: Chaumeton, François-Pierre. Flore médicale. 1832.

Another factor was preparation, whether that be seasoning, spices, sauce, boiling, roasting, etc. These processes and additions could modify the properties of food and make them more or less hot/cold/dry/moist. Beef was usually understood as having the properties of “cold” and “dry,” as meat was usually taken from older cows that could no longer be used for milk or strength. Because of this “dry” property, it was said that beef should not be roasted, as roasting confers the property of “dryness” through cooking over an open flame and drying out the meat. Instead, the cold and dry properties should be balanced out through boiling and then using a sauce (such as an onion sauce), as the two processes would then moisten and warm the cold, dry meat. This way the qualities of the beef could be balanced out and no longer pose a risk of rendering the consumer melancholic.

It was with this knowledge that people could balance their excess humors with food. Cooks in the late medieval period seemed conscientious of the humoral properties of their ingredients and finished dishes. Some used specific herbs and foods that were hot and dry to counteract cold and wet properties – properties that matched the qualities of sicknesses such as the flu or common cold. Indeed, recipes from the 14th and 15th centuries showed an active awareness of how food preparation and choice could influence the health of households.

MORE LIKE THIS

Curious about humoral theory and the seasons? Read more and find out with our blog article, “Humoralism and the seasons.”

Check out our exhibit, “Long shalt thou live, if these well be done: Food, Drink and Health” on display through October 18, 2023, on the seventh floor of Becker Medical Library. Explore the medical uses of food, drink, and diet in our rare book collections, beginning with ancient Greece and medieval Europe through 19th and 20th century America.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albala, K. (2002). Eating right in the Renaissance. University of California Press.

Dendle, P., & Touwaide, A. (2008). Health and healing from the medieval garden. The Boydell Press.

Galen. (2007). Galen on the properties of foodstuffs. (O. Powell, Ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Grant, M. (2000). Galen on food and Diet. Routledge.

Lyon, K. (2015, December 4). The four humors: Eating in the Renaissance. The Four Humors: Eating in the Renaissance . https://shakespeareandbeyond.folger.edu/2015/12/04/the-four-humors-eating-in-the-renaissance/

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). “And there’s the humor of it”: Shakespeare and the four humors. U.S. National Library of Medicine.