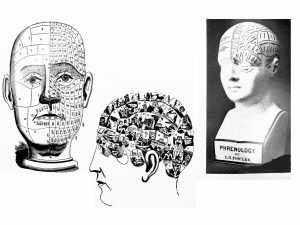

Phrenology Definitions

Phrenology has many definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary. My favorite is:

The theory that the mental powers or characteristics of an individual consist of separate faculties, each of which has its location in an organ found in a definite region of the surface of the brain, the size or development of which is commensurate with the development of the particular faculty; the study of the external conformation of the cranium as an index to the position and degree of development of the various faculties. (Phrenology, Oxford English Dictionary c 2016)

Phrenology exemplified and Illustrated

Phrenology was popular in 1836 when it came to Boston, Massachusetts, the home of the artist and author, David Claypoole Johnston (Colbert 1997, 258). He had already attracted an audience by poking fun at fad and fashion in Scraps 1-6, six illustrated pamphlets he published earlier. Scraps No. 7, where he poked fun at phrenology, was an immediate hit and went through two printings in 1836 and 1837.

Phrenology was popular in 1836 when it came to Boston, Massachusetts, the home of the artist and author, David Claypoole Johnston (Colbert 1997, 258). He had already attracted an audience by poking fun at fad and fashion in Scraps 1-6, six illustrated pamphlets he published earlier. Scraps No. 7, where he poked fun at phrenology, was an immediate hit and went through two printings in 1836 and 1837.

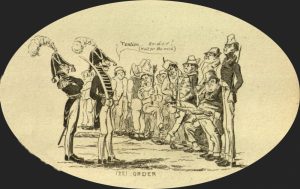

Phrenology Illustrated and Exemplified, or Scraps No. 7, with its masterful caricatures is a parody of the numerous books and pamphlets on phrenology. It mimicks their arrangement and content. Thirty-nine mental powers or characteristics of an individual are explained in text and plates in the numerical order according to their location on the phrenology head. My favorite characteristic or faculty in Scraps No. 7 is order, because the military unit caricatured is the antithesis of order and the explanation and examples are hilarious. I also enjoy the 6 caricatures in which Johnston lampoons phrenology, himself, and the patrons of his art.

22.— ORDER.

See Order on no. 22 Plate 3.

“There are individuals, even children,” says Spurzheim, “who like to see every piece of furniture, at table every dish, and in their business every article, in its proper place.” This propensity arises from Order, which likewise tends to cleanliness or tidiness.

The good housewives of New Amsterdam were liberally gifted with this organ ; “so addicted were they to scrubbing and scouring, that some of them,” (says an author quoted by Knickerbocker,) ” grew to have webbed fingers like a duck.” It was moreover the opinion of this author, that many of them had acquired tails like mermaids. Knickerbocker’s Marvellousness, however, it is but justice to add., was not so full as to yield entire faith to this assertion. And instances of a similar powerful action of the organ have not been rare among the notable housewives of New England. The reader has undoubtedly heard of the good old dame who scrubbed her floor so often and so thin, that she fell through it, mop, bucket and all.

The inhabitants of New Nederlandts, both male and female, seem to have been great sticklers for Order. When the great Peter Stuyvesant was about to make a desperate charge upon his enemy, the Swedes, he turned pale. “For once in his life, and only once,” says the historian, ” did the great Peter turn pale ; for he verily thought his warriors were going to falter in this hour of perilous trial, and thus tarnish forever the fame of the province of New Nederlandts.”

“But soon he discovered, to his great joy, that in this suspicion he deeply wronged this most undaunted army: for the cause of this agitation and uneasiness, was simply, that the hour of dinner was at hand, and it would have almost broken the hearts of these regular Dutch warriors, to have broken in upon the invariable routine of their habits.” (Johnston 1837, page 11)

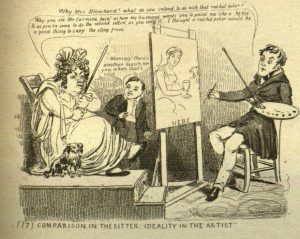

D.C. Johnston lampoons himself

17.— IDEALITY

17.— IDEALITY

This faculty,” says Combe, ” produces the desire for exquisiteness and perfection, and is delighted with what the French call Le beau ideal. It is the faculty which gives inspiration to the poet.”

” That a poet must be born,” says Spurzheim, “has passed into a proverb, and education is generally acknowledged inadequate to produce poetic talent.” This organ, beside being absolutely requisite to the perpetrator of verse, is likewise needful to those destined to receive it, otherwise it operates medicinally, generally as an emetic, except in cases of defective Watchfulness, when it acts as a soporific ; a rabid dog will turn from the music of the ripphng stream with less loathing, than some individuals evince at the sight of a gushing fountain of purest Helicon. I have known instances where the reading of a single book of that most sublime of all sublime effusions of the poet’s brain, the Fredoniad, has produced the full effect of the most powerful exterminating medicines. Deficiency of Ideality is one of the characteristics of Hotspur, who says

‘ I would rather be a kitten and cry mew. Than one of these same metre ballad mongers I had rather hear a brazen canstick turn’d. Or a dry wheel grate on its axletree : And that would set my teeth nothing on edge, Nothing so much as mincing poetry.”

The author of the Puritan evinces as little ideality as Hotspur. Having witnessed the performance of Macbeth, he thus notices the incantation scene : ” We saw nothing but a company of ridiculous old women talking mummery whilst they were boiling a pot.” (Johnston 1837, page 9)

![Faculty no. 19: Veneration [for the artist]](https://becker.wustl.edu/wp-content/uploads/19-Veneration-for-the-Artist-Scraps-No-7-1837-Plate-2-300x202.jpg) 19.— VENERATION.

19.— VENERATION.

On [No. 19,] Plate 2, I have attempted to illustrate a very common species of Veneration.

” The function of Veneration,” says Combe, ” is to produce the sentiment of Veneration in general, or an emotion of profound or reverential respect, on perceiving an object at once great and good. It produces respect for titles, rank and power: for a long line of ancestry, or mere wealth, and it frequently manifests itself in one or other of these forms, when it does not appear in religious fervor. When vigorous and blind, it produces complete prostration of the will and the intellect, to the object to whom it is directed.”

Sancho Panza evinced this feeling, (though the organ was too well thatched to be made visible in his portraits,) and at one time proposed to his master, when nearly weary of knight-errantry, that they should both turn saints. …Walter Scott’s Tony Fire-the-faggot is brim-full of Veneration: he delights as much to see a roasted heretic as a roasted pig.

The early inhabitants of Massachusetts were no less remarkable for Veneration than Tony. “They employed their leisure hours,” says the learned Knickerbocker, “in ban-

ishing, scourging or hanging divers heretical papists, quakers, and anabaptists, for daring to abuse the liberty of conscience: which they clearly proved to imply nothing more than that every man should think as he pleased on matters of religion, provided he thought right : for otherwise it would be giving a latitude to damnable heresies.”

Some of the descendants of these worthies are liberally endowed with Veneration, both patriotic, and religious. To the promptings of the former we are indebted for a granite pile, (commemorative of the glorious deeds of heroes ” dead and turned to clay,”) whose pyramidal top, even in the clearest atmosphere, is invisible to the naked eye ; whilst the activity induced by the latter feeling, completed, in one night, a monument unequalled in the country, which renders immortal the valiant and holy achievements of certain warriors, who risked their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honors, in the cause of that religion which teaches charity to all mankind.

The Marylanders, in the time of Wilhelmus Keft, were deplorably deficient in Veneration. Knickerbocker describes them as a gigantic, gunpowder race of men, living on

hoe-cake and bacon, mint julaps and apple toddy. A colony of these monsters having planted themselves on the borders of the Schuylkill, within the province of the Nieu Nederlands, Admiral Jan Jason Alpendam was despatched by the Governor with a fleet of two sloops, to disperse the intruders, and regain possession of the country. ” On arrival at the place of destination,” says the historian, ” he attacked the enemy in a vigorous speech in low Dutch, which the wary Keft had previously put in his pocket, wherein he courteously commenced by calling them a pack of lazy, lousy, dram-drinking, cock-fighting, horse-racing, slave-holding, tavern-haunting, sabbath-breaking, mulatto-breeding upstarts, and concluded by ordering them to evacuate the country immediately:” to which they laconically (and irreverently, I shouM have said,) replied, that “they’d see him d ” but liere my Reverence interferes, and will not suffer me to write the blasphemous reply of these ruffians. Suffice it to say, that no sooner did the answer reach the ears of the courteous and magnanimous Admiral, than he indignantly tacked about, and on his arrival at New Amsterdam was received with distinguished honors, and unanimously called the deliverer of his country : nay, more, such was the veneration of the worthy inhabitants of New Amsterdam, not only for the gallant Admiral, but for the sloops under his command, that the latter, having done their duty, were laid up in a cove, now called Albany basin, and supported in idleness dur-

ing the remainder of their existence ; whilst the name of the former was immortalized by a shingle monument, which was commenced and finished on Flatten Barracks Hill. (Johnston 1837, pages 9-10)

36.—LOCALITY.

![Faculty no.36: Locality [D.C. Johnston's place of business] Faculty no.36: Locality [D.C. Johnston's place of business]](https://becker.wustl.edu/sites/default/files/imagecache/original/36%20and%2037%20Locality%20%2526%20Mirthfulness%20-%20Scraps%20No%207%20%281837%29%20Plate%204.jpg) Of this organ Spurzheim says: ” It seems to me that it is the faculty of Locality in general: as soon as we have conceived the existence of an object and as qualities it must necessarily occupy a place; and this is the faculty that conceives the places occupied by the objects, surround us.” The memory of places, therefore is a function of this organ-a function which Goldsmith has represented particularly deficient in Mrs. Hardcastle (in She Stoops to Conquer,)-who thinks herself forty miles from home, when scarcely forty rods, and does not recognize her own horse pond, even after a portion of its contents has passed down her alimentary canal. …

Of this organ Spurzheim says: ” It seems to me that it is the faculty of Locality in general: as soon as we have conceived the existence of an object and as qualities it must necessarily occupy a place; and this is the faculty that conceives the places occupied by the objects, surround us.” The memory of places, therefore is a function of this organ-a function which Goldsmith has represented particularly deficient in Mrs. Hardcastle (in She Stoops to Conquer,)-who thinks herself forty miles from home, when scarcely forty rods, and does not recognize her own horse pond, even after a portion of its contents has passed down her alimentary canal. …

A propensity to travel, and a desire for locomotion, are induced by this organ. Combe says, ” it is full in the busts of Columbus, Mungo Park, and Cook.” Not George Frederick—he was more remarkable for his frequent inability to perform locomotion,—but Captain Cook, the circumnavigator. … (Johnston 1837, 17)

![Faculty no.38: Acquisitiveness [in Scraps no. 7 readers]](https://becker.wustl.edu/wp-content/uploads/38-Acquisitiveness-Scraps-No-7-1837-Plate-4-opt-300x250.jpg) 38.— ACQUISITIVENESS.

38.— ACQUISITIVENESS.

*’ This faculty,” says Spurzheim, “reduced to its elements, consists in the propensity to covet, to gather together, &c.”

The organ was first discovered in persons prone to make irregular appropriations, and was thence called the organ of Theft. ” Combe says, ” it is difficult to conceive a miser, without great endowment of this propensity.” When moderate, it tends only to economy, and prevents unnecessary expenditures. The organ was full in sergeant Thorp, who on los- ing his leg, at the battle of Saratoga, congratulated himself, on the sudden reduction of his wardrobe expenses. …

Some of the brute creation are endowed with this faculty. It is also possessed by many of the insect tribe — such as the ant, the bee, and the spider. In the last mentioned individual, it is happily illustrated by Hogarth, who in one of his prints, represents a spider’s web, drawn over a church poor box : the web, being unbroken ; the inference is, that the. spider has intercepted the donations, and deposited them in his own box. See Acquisitiveness on Plate 4. (Johnston 1837, page18)

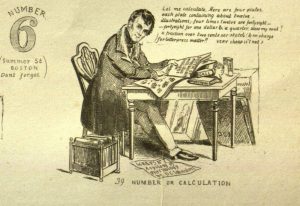

39.— NUMBER OR CALCULATION.

39.— NUMBER OR CALCULATION.

“The special function of this faculty,” says Spurzheim, “seems to be calculation ‘in general.” Dr. Gall calls it, Le sens des nombres, and while he states distinctly, that arithmetic is its chief sphere, he regards it also as the organ of mathematics.

It is full in the portraits of Mr. Joulter, who undertook, by mathematical demonstration, to convince his pupil. Peregrine Pickle, of the evil of his ways, and the consequences that must follow.

Shakspeare has drawn Cloten, in Cymbeline, piteously deficient in Calculation : he ” Cannot take two from twenty, for his hearty and leave eighteen.”^ Falstaff’s error, in computing the number of rogues in buckram suits, that let drive at him, is attributable to deficient Calculation. (Johnston 1837, page 18)

Bibliography

1. Colbert, Charles, 1946-. A Measure of perfection : phrenology and the fine arts in America. Chapell Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Becker catalog record: http://beckercat.wustl.edu/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=9975

2. Johnston, David Clayppole, 1799-1865. Phrenology exemplified and illustrated : with upwards of forty etchings : being Scraps no. 7, for the year 1837. Boston: [Publisher not identified], 1837.

Becker catalog record: http://beckercat.wustl.edu/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=183334

NLM Digital digital copy: https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-7705501-bk

Internet Archive digital copy: https://archive.org/details/7705501.nlm.nih.gov

3. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, c 2016.