It reads like the beginning of a horror story.

“At 8 o’clock Monday evening three very rough-looking men entered a saloon known as the ‘Gravois Cave’ on a corner opposite of the cemetery…The men remained only a few minutes and when they went out they separated going in different directions and leaving a light spring-wagon, in which they had driven up, standing at a hitching post. They had been gone perhaps the greater part of an hour when they returned and again patronized the bar to the extent of several rounds of drinks. Their appearance had been rough enough before, but now, if possible, it was infinitely worse. Their bronzed hands and wrists were dirty, their boots covered with mud, their trousers rolled up or stuck in their boots bore unmistakable evidence of contact with fresh clay, while even their slouched hats were besprinkled with the same material. After a few minutes’ stay, they went out, climbed up in the wagon and drove away into the darkness.”

And so begins the account of the case of Ernst Doepke, one of the few, if not one of the last, people in St. Louis to have been arrested for grave-robbing. He might have gotten away with it had it not been for the saloon keeper, John Stromberg, who “had not lived in the world so long without learning a thing or two.” He had recognized Doepke, who was “known to be a vault cleaner,” and had set out to warn the cemetery’s guard. The rest of the newspaper article, which appeared in the December 15, 1875, issue of the local daily, The St. Louis Republican, tells how Stromberg and his fellow citizens confronted Doepke and his conspirators at the gates of the cemetery and held them for the police. According to the article, their wagon was found to contain picks, spades, a coffin and a corpse wrapped in a blanket – “the incontrovertible proofs of their work.”

The sensationalism of the article is only partially the result of 19th-century journalistic license – it also reflected the moral outrage and fear felt by many at the time toward the so-called resurrectionists; men who seemingly had no concern for disturbing the peace of the dead. Personal sentiment and religious beliefs helped reinforce the public’s natural revulsion toward the desecration of the dead, but those feelings were increasingly challenged by the growing needs of medical training.

With the founding of the Missouri Medical College in 1840 and several other medical schools soon after, there was suddenly a demand in St. Louis for human remains for anatomical instruction. Cadavers for medical study were mostly sourced from the relatively large number of unclaimed bodies in the city’s hospitals and mortuaries.

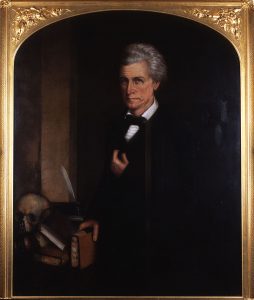

But emotions often ran high over the fears. In 1844, a riot broke out when some children allegedly discovered human bones in the yard of the St. Louis Medical College. Another time, a young girl went missing from her home. Her family, part of the German immigrant community, feared that she had been taken to the Missouri Medical College for dissection and a large party of German St. Louisians rushed into the school. The founder and anatomy instructor of the college, Joseph Nash McDowell, later told how he hid from the mob among the cadavers in the autopsy room by lying on one of the dissection tables covered in a sheet.

Around the time of Doepke’s arrest, the Missouri legislature had created the State Anatomical Board, which would oversee the distribution of human remains to medical schools. The bodies of the recently deceased that were unclaimed within 48 hours were able for dissection. However, there were whispers that sometimes the supply never quite met the demand. Where, then, did the needed bodies come from?

It was no secret – barkeeper John Stromberg recognized Doepke as a “vault cleaner.” In fact, in the city’s census and directories, Doepke listed his occupation as a driver and vault cleaner. It was in this capacity that he was known to the medical schools of St. Louis. “Vault cleaner” is not a job title used today, but it described someone who removed the human remains left after the dissection classes.

It was a somewhat regulated position. In 1865, Doepke had won the contract from the City of St. Louis to haul away the city’s slop and “night-soil,” which was the euphemism used for organic waste from kitchen and homes, like animal parts and human feces. Doepke also reportedly had a contract to bury the bodies of the indigent who died in the city’s hospitals. He made his living transporting the dead and other unpleasant matter, which would have been a serious danger to public health without adequate removal and controls.

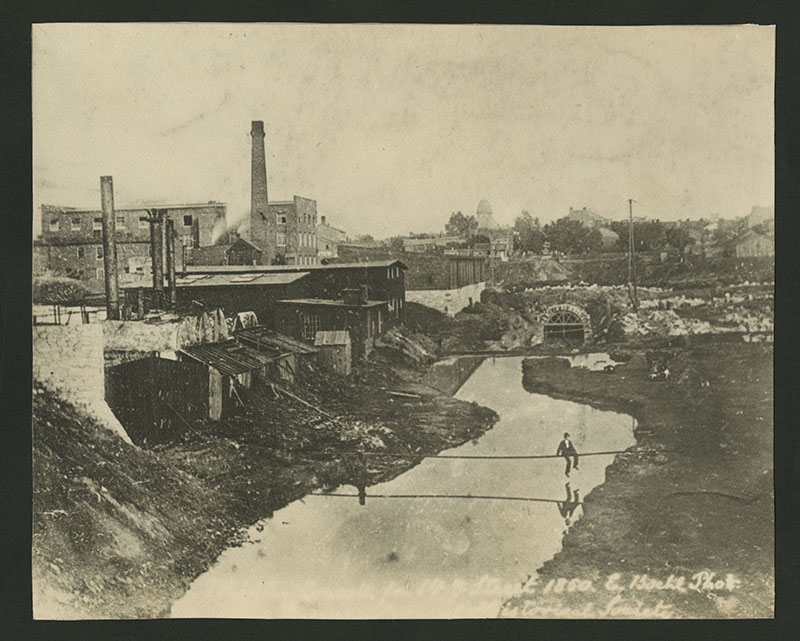

The rapidly growing city of St. Louis created dangerous sanitation issues. Mill Creek, which had been dammed to form Chouteau’s Pond, was also used as an open sewer. The filthy conditions of the pond would lead the city to drain it and divert the flow of the creek into buried sewers which would flow into the Mississippi.

Having the duty to transport and bury the city’s indigent in the municipal cemetery, or “potter’s field,” Doepke would also likely have been involved in the legitimate distribution of cadavers to medical schools.

At the time of his arraignment, some in the city were concerned Doepke would be supported in his defense by the faculty of the medical schools, but the newpapers reported that was not likely to be the case. “It was understood that up to a year [prior to his arrest] Doepke was supplying some of the colleges with subjects for dissection, but that he had a crooked way of dealing, shipped the choicest stiffs away to Ann Arbor and other places, and played his employers here some bad tricks. He thus lost their patronage.”

But this may not have been entirely true. Not much remains of the records of the early medical colleges in St. Louis, but the cash book for the Missouri Medical College for the years 1877-1900 survives. On May 24, 1877, while his case was still on appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court, Doepke was paid $40 by the College for cleaning the vault. Obviously, his conviction and ongoing appeals did not dissuade the Missouri Medical College from hiring him. Perhaps there weren’t many with a stomach for this macabre undertaking.