Pabst, Patent Medicines, and the Pursuit of Profits

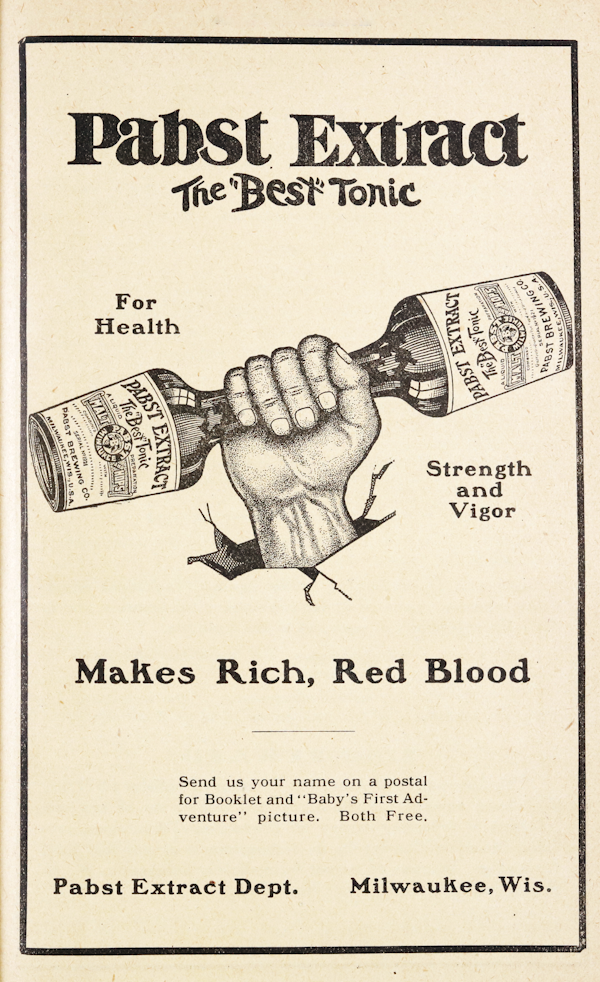

Pabst may be best known today for PBR— beloved beer of cheapskate hipsters nationwide—but at the turn of the 20th century, the company was also brewing up a beverage called the “Best” Tonic. You might expect a malt brew with as much as 5% ABV to be a beer, but Pabst apparently liked to think outside the keg. They said their tonic was not for toasting to your health, rather it was for your health. In other words, the “Best” Tonic was not beer; it was medicine.

Why would the company behind the blue ribbon stoop to such subterfuge? Why would Pabst prevaricate so publicly about their product? For the ladies, of course.

A Tonic Boom

Pabst Brewing Company, then known as the Philip Best Brewery, introduced the “Best” Tonic in 1888, when tonics were a staple in the patent medicine pantry. Tonics of all varieties were thought to strengthen the body and also increase one’s vim, vigor, and vitality. One kind of tonic that was new on the market in the late nineteenth century was a malt tonic, and malt, as one of the key ingredients in beer, was something Pabst knew a lot about.

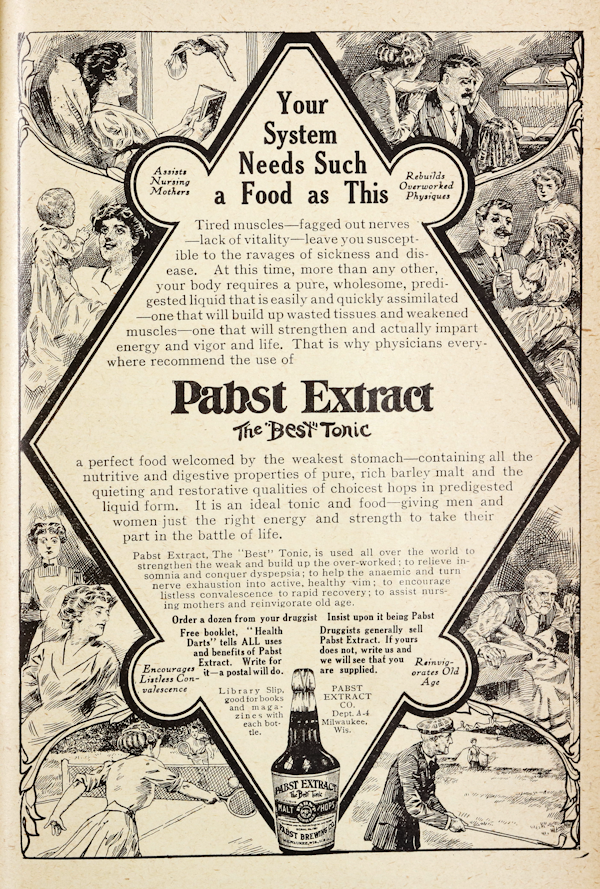

Part of the hype about malt tonics was that their benefits supposedly went beyond maximizing muscle mass and inciting extra energy. At the time, people believed malt tonics would also aid digestion for the very reason malt was used to make beer: it contains enzymes that break down starch into sugars. Like other breweries, Pabst ran wild with this idea and heavily promoted the “Best” Tonic, also known as Pabst Extract, as a proprietary medicine. In the 1910 ad below Pabst describes their tonic as a “pure, wholesome, predigested liquid” that contained “all the nutritive and digestive properties of pure, rich barley malt.”

However, the “Best” Tonic also included another ingredient, malt’s bosom buddy in beer-making: hops. As the ad says, hops provided “quieting and restorative qualities.” Together, the two ingredients teamed up in the “Best” Tonic to “strengthen the weak and build up the over-worked; to relieve insomnia and conquer dyspepsia; to help the anaemic and turn nerve exhaustion into active, healthy vim” and even “to encourage listless convalescence to rapid recovery….”

And how might one conquer dyspepsia and achieve active, healthy vim? By drinking just one (1) wineglass of tonic, at every meal—and at bedtime—every day. A bottle a day, more or less. Customers could of course purchase Pabst’s tonic by the case—for convenience.

If a malt and hops beverage you drink by the glass kind of sounds like beer to you, you’re kind of not wrong. And if you are thinking that Pabst was all but promoting the idea “multiple beers a day keep the doctor away,” you are in good company, because that is essentially what they were doing.

A Beer by Any Other Name

Was Pabst’s “Best” Tonic actually beer, or might the tonic’s magical marriage of malt and hops be nonalcoholic after all?

Reports of how much alcohol the “Best” Tonic contained do vary over the years, but the results always came in on the side of unquestionably alcoholic. A chemical analysis published in 1897 found Pabst’s tonic to contain as much as 5.16% alcohol, while a bulletin from 1916 reported the beverage contained just 3.83%. Even Pabst itself, in 1902, said it was 4.5% alcohol.

So yes, it was beer.

Except that Pabst said it wasn’t. A Pabst brochure in 1902 even said it with hyphens to make it extra clear: “It-is-not-beer.”

Pabst went to great lengths to claim that “Best” Tonic was not beer. They claimed it wasn’t beer because doctors said so. (However, the doctors that provided those testimonials may or may not have existed.)

They claimed it wasn’t beer because the US government said so. (Pabst said the commissioner of Internal Revenue had ruled that the “Best” Tonic was not a beverage or malt liquor, but a proprietary medicine instead. The commissioner of Internal Revenue had not.)

They claimed it wasn’t beer because it had less alcohol than other patent medicines. (Perhaps, but “four and five-tenths per cent” alcohol… is still four and five-tenths per cent alcohol.)

They even claimed that while it was made like beer, looked like beer, and tasted like beer, Pabst intended the “Best” Tonic to be medicinal, so it just wasn’t beer. A 1917 ad proclaimed:

“While made principally from malt and hops and greatly resembling in both taste and appearance dark beer or porter, Pabst Extract, The “Best” Tonic, differs materially from either of these beverages owing to its being brewed from a medicinal standpoint …”

Pabst may have wished for a reverse water-into-wine type miracle, but alas, wishing did not make their alcoholic malt tonic into medicine. So why go to all the effort to pretend their beer wasn’t beer? For the love of women.

Where My Ladies At?

The sole reason for all this tomfoolery and taradiddle? Sweet, sweet market expansion. In the late nineteenth century, beer was mainly sold in saloons, but saloons—those derelict dens of vice and iniquity—were not welcoming places for most women. That meant a goodly portion of the adult populace was not buying Pabst beer—but they could be, if only beer could be sold at places women were welcomed. Places like drugstores.

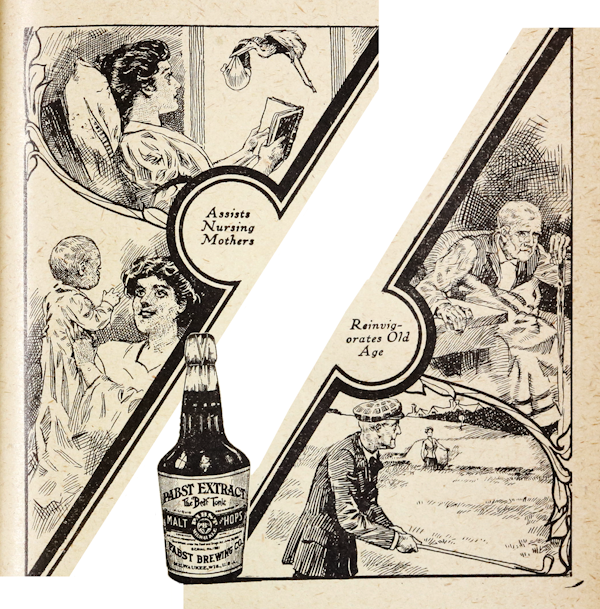

And so it was. Pabst packaged their not-beer-but-beer product to fit on pharmacy shelves with other patent medicines. Through massive advertising campaigns, they made malt-based medicine available to women nationwide. Working women, nursing mothers, and ladies laid up after long illnesses were all beneficiaries of specially targeted marketing of the beer-based cure-all.

Later, Pabst would expand their market for the “Best” Tonic to men and the elderly as well, promising the tonic “Rebuilds Overworked Physiques” and “Reinvigorates Old Age.” However, we have women to thank for being the original inspiration behind this peculiar confluence of kegs, quackery, and capitalism.

For more musings on medical ads, check out our blog posts on trading card advertisements for Sapanule and Ayer’s Pills. Or, come to Becker Archives and Rare Books to find some of your own in publications like Polk’s Medical Register and Directory, The National Druggist, and Hygeia.

Sources

Estes, J. Worth. “The Pharmacology of Nineteenth-Century Patent Medicines.” Pharmacy in History 30, no. 1 (1988): 3-18.

McGill, A. Malt Extracts. Ottawa?: Inland Revenue Department, 1916?.

Mickey, Thomas J. “Alcohol as Medicine.” In Deconstructing Public Relations: Public Relations Criticism, 19-45. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 2003.

Hoverson, Doug. Land of Amber Waters: The History of Brewing in Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Ogel, Maureen. Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer. Orlando: Harcourt, Inc., 2006.

O’Hagan, Lauren Alex. “Blinded by Science? Constructing Truth and Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Virol Advertisements.” History of Retailing and Consumption 7, no. 2 (2021): 162-192.

Stevens. A.A. “Tonics.” In Modern Materia Medica and Therapeutics, 289. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1909.