Mallory Rodell is a graduate student at the University of Missouri who is completing a practicum at the Becker Archives during the Spring 2024 semester. She is the author of this post and a guest contributor to the Becker Blog.

Julia Catherine Stimson was born in Worcester, Massachusetts on May 26, 1881. She lived in St. Louis briefly as a child from 1886 to 1893 while her father, Henry Albert Stimson, served as pastor of Pilgrim Congregational Church. When she was 12 years old, Stimson and her family moved again to New York City when her father founded the Manhattan Congregational Church. She graduated from the private all-girls Brearley School in 1897.

Stimson began her college studies at Vassar at the age of 16, and received her BA in 1901. She then attended Columbia University to complete graduate work in biology, and Cornell University Medical College where she studied medical illustration. In 1904, she began her nursing training at the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses, and completed her RN degree in 1908.

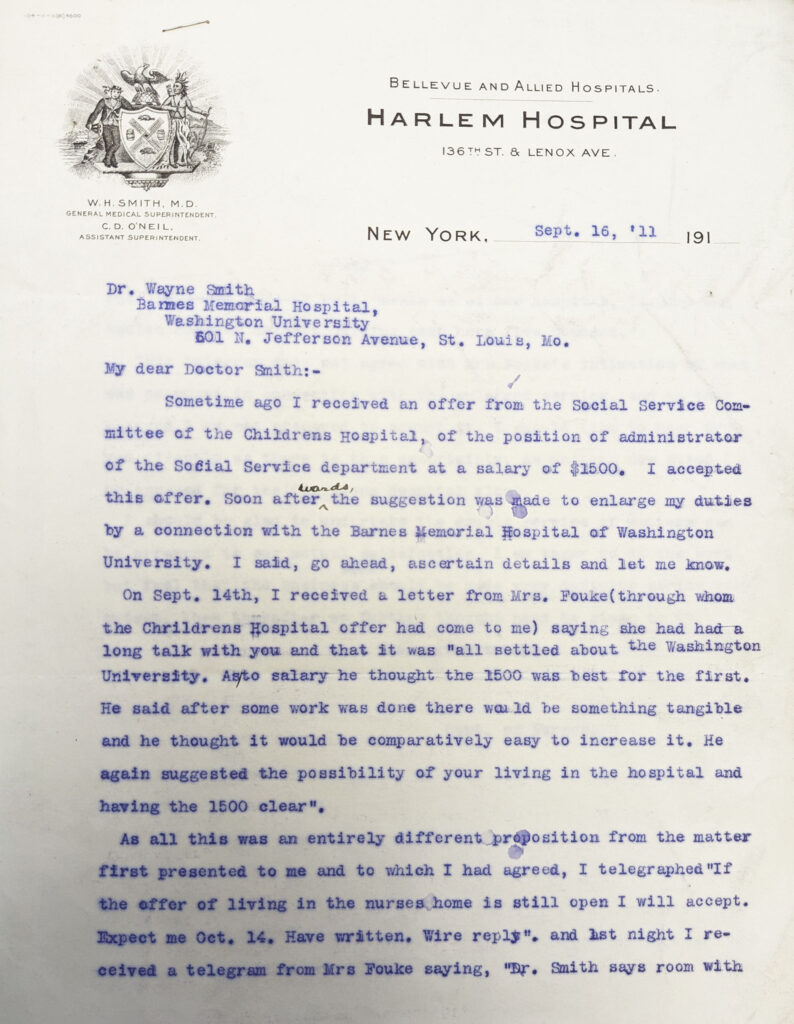

Now 27 years old, Stimson’s first job after graduation was serving as the Superintendent of Nurses at the newly opened Harlem Hospital. During Stimson’s three years in this position, she collaborated with her colleagues to create a Social Service Department. This experience, along with her extensive educational training, made her well suited to play an important role in the development of the rapidly growing field of medical social work.

In 1911, Stimson became director of social service at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, which had just affiliated with Washington University the previous year. Shortly thereafter, her duties expanded to include leading the social service department at Washington University Hospital, and then at Barnes Hospital as well when it opened in 1914. Also in 1914, she began serving in a dual role as both the director of the social service department at Washington University’s affiliated hospitals and the superintendent of the Training School for Nurses.

Stimson’s passion for her work encouraged others to become involved. During her time in St. Louis, she was able to create a group of volunteers to support the Social Service Department by spending time with patients at the hospital and making pre-discharge visits to evaluate sanitary conditions in patient’s living conditions. Stimson also continued her dedication to education, and received a Master’s degree in sociology from Washington University in May 1917.

Shortly after the US declared war on Germany in 1917, Stimson resigned from her role at Washington University Medical School in order to enlist in the Army Nurse Corps. Later that year, a group of 28 officers, 141 enlisted men, and 65 nurses from Washington University left St. Louis for Rouen, France where they staffed Base Hospital 21. Stimson served as Chief Nurse of this unit, where she was faced with many personal and professional struggles including inadequate resources and gender bias. In various accounts of Stimson’s service during the war, she was said to have “superb organizational skills1,” achieved “extraordinary service2,” and maintained “compassion and commitment3.” Stimson’s ability to prove herself as capable, even in times of great distress, allowed her to move up the ranks of the Army quickly. In April 1918, she was assigned to the American Red Cross in Paris as chief nurse and later promoted to chief nurse of the American Expeditionary Forces in France. The profound effect that the war had on Stimson is documented in Finding Themselves, a book composed of the letters she wrote to her family during her time abroad.

In the two excerpts below taken from Finding Themselves, Stimson commented on the professional and personal difficulties faced during the WWI:

“It takes about half an hour or more to read about the admissions, discharges, operations, the condition of all the “S.I’s” (Seriously Ill) and “D.I.’s” (Dangerously Ill), and to hear that there did not seem to be enough blankets for the outgoing convoy, many of whom were stretcher patients, that there is difficulty about coal for some of the tents at night, about this or that nurse’s good work when so and so had such a terrific hemorrhage, and that an incoming convoy is just being unloaded, apparently very badly wounded cases, but no report on them as yet.”

“You can’t imagine what fun we have talking about what we will do first when we get home. It is a favorite game…A whole lot want some kind of bread stuffs, muffins, biscuits, popovers, waffles, pancakes. That is what I want among other things, but most of all I want to see my family and my friends.”

At the conclusion of her service in France, Stimson never returned to social work. Instead, she focused on nursing for the rest of her career. In 1919, she was appointed the dean of the Army Nursing School and superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps, where she advocated for her students, the resources needed for them to succeed, and the reputation of her school. Stimson fought to provide equal opportunity for her students to achieve the same recognition as their male counterparts.

She remained at the Army Nursing School until its closure in 1933, and remained with the Army Nurse Corps until her retirement in 1937. After the US entered WWII, she returned to public service in 1942 to head the Nursing Council on National Defense. Stimson’s dedication to the United States Army in times of need did not go unnoticed. Stimson was the first woman to achieve the rank of Major in the United States Army and was promoted to the rank of Colonel in August 1948, just six weeks prior to her death.

Julia C. Stimson died on September 29, 1948 in Poughkeepsie, New York. After her death, the Executive Faculty of Washington University School of Medicine recognized Stimson in a resolution on December 4, 1948, as a “professional leader in medical social service and in nursing.” Stimson was a pioneer and dedicated her life to the improvement of the fields she served in, the professional lives of those who worked in those fields, and the lives of those that they served.

For more information regarding Julia Stimson and Base Hospital 21, you may use the Becker Archives Database to browse a wide selection of the items from the Base Hospital 21 Collection. You may also contact the archives staff to ask questions or schedule an appointment via email at arb@wusm.wustl.edu.

Sources:

1. Hunt, Marion. (1999). Julia Catherine Stimson and the Mobilization of Womanpower. Gateway Heritage, 20(3), 44-51.

2. O’ Connor, Candace. (2003). “Over There”: World War I and Washington University, Washington University Magazine, 73(4), 18-21.

3. Sarnecky, Mary T. and Gurney, Cynthia A. (1992). A Snapshot of an Army Nurse Leader in the Great War. Military Medicine, 157(4), 169-174.